Pro tip: One of the best ways to score points in a seminar is to say that whatever you’re discussing—be it a novel, film, videogame, etc.—is actually a meditation on its medium. Shakespeare’s sonnets? Not about love; they’re about writing poetry. Ulysses? Not about a day in Dublin; it’s about the history of English prose.

The fact that this always works tells us two things: 1. We don’t understand any medium fully. 2. Art’s meaning is always inextricable from its medium. (It also tells us that English class is a little too easy to game.)

Enter The Magic Circle. If there were ever a game that was going to get “meta” as a free-standing adjective slapped on it—a game that is about nothing if not its medium—this is the one. You play a playtester working on a still-in-development game 20 years in the making that has spent the last 10 years sprinting to nowhere. It is the Smile of videogames, which was the Apocalypse Now of albums, which was the In Search of Lost Time of movies, which was the Duke Nukem Forever of novels. (Aside: The Magic Circle was originally released on Steam’s Early Access platform and, considering how perfect that is for its game-within-a-game plot, I have no idea why they ever took it out.)

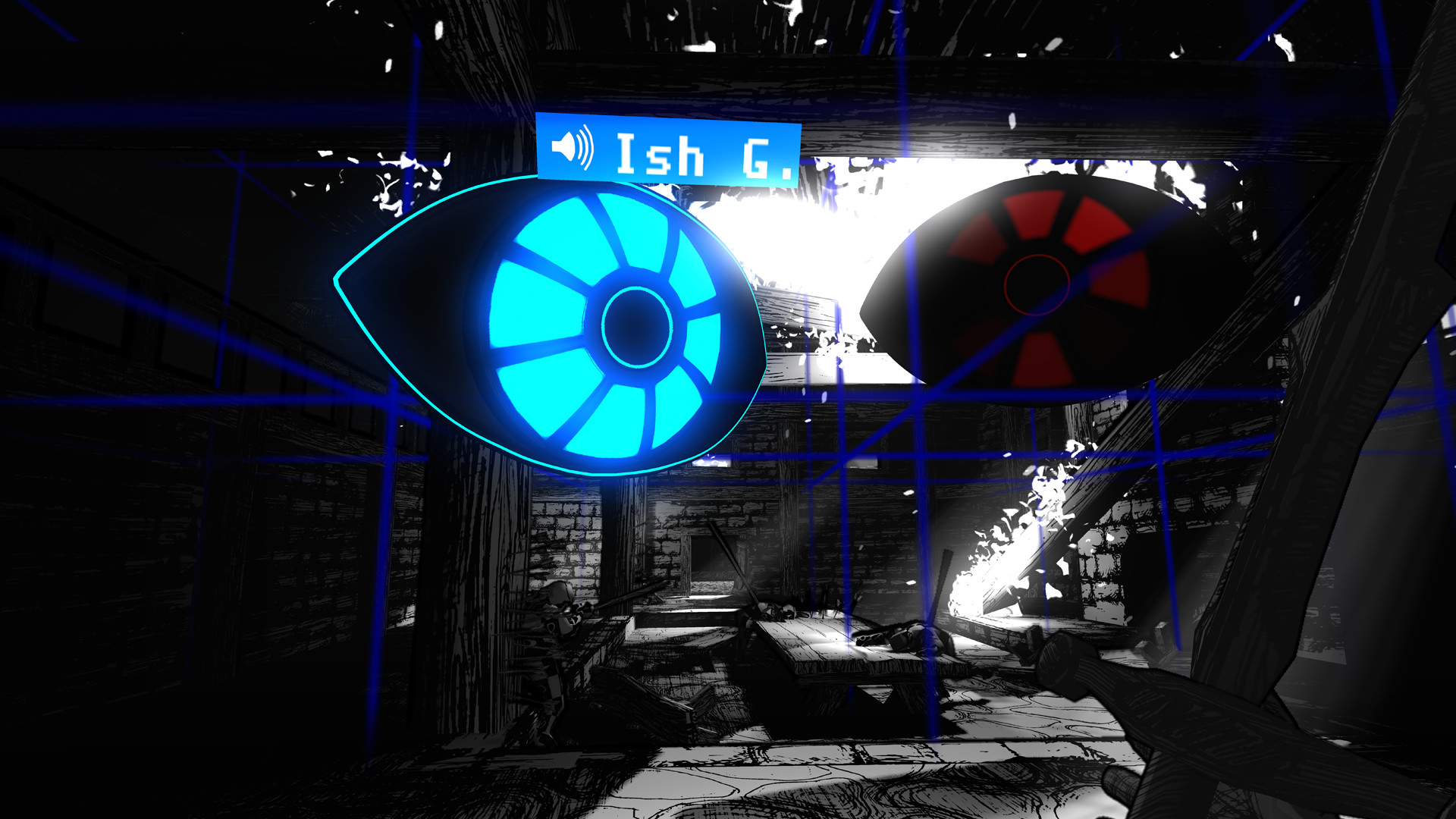

The world of The Magic Circle is a jumbled mess of half-finished ideas, overblown ambitions, long boardroom meetings, and the conflict between whiteboard and what can really be done. If it were the work of an individual, the geography of The Magic Circle would tell the story of a fragmented and fragmenting mind, the solitary genius locked in a room losing her humanity in order to make her art. Instead, The Magic Circle’s world—bridges leading nowhere, music with the conductor’s whispers left in, a sausage-shaped textureless protagonist because no decision could be reached about any characteristic he or she actually has—represents everything that goes wrong when art must be a collective process. Competing interests clash, ideas are vindictively implemented by one person then quietly deleted by another, and the final product represents a set of unwelcome compromises on the part of everyone involved.

I can’t imagine how on-the-nose this must feel for actual game developers; I got frustrated trying to be entertained by it.

As a subversive playtester, your goal is to use the game’s systems against itself, finding forgotten parts of its codebase, bringing them back into the game world, and seeing what kind of trouble that causes for the developers. You’re wreaking havoc inside of The Magic Circle because it seems to entrap everyone who touches it: the manic project lead who has been writing this sequel since its original 1980s text-based predecessor; the old pro-gamer-turned-developer who is bitterly, contractually obliged to keep working on the game; the intern/disciple who does the project lead’s bidding as a part of the fanbase foaming at the mouth for a sequel; and the art director and level designer, whose constant bickering manifests itself in passive-aggressive manipulation of the environment, gleefully breaking whatever the other was trying to fix.

It’s a stressful situation amplified by years of small, unresolved crimes against one another, and the game’s tone—affecting a light touch but straying closer to black comedy—actually manages to make it more stressful. Maybe this is deliberate. Maybe The Magic Circle (the game within the game The Magic Circle) is a failure that even fails to fail.

But the thing The Magic Circle does best is destroy itself. As you progress through the story, you learn to strip items and enemies in the game of their properties (fireproof, magical, electrified, walking, whatever) and, in the manner of Dr. Frankenstein or a cook trying to use up everything in the fridge, you recombine elements of the world to make new, grotesque-yet-functional additions to it. These allow you to solve puzzles, fight enemies, and destabilize the game world. Of course, thematically, that destabilization is both necessary and helpful. There’s a spirit of revolt in your work, a rhetoric of mortals killing the gods competing for control of The Magic Circle. You have to destroy this world to save the people who made it, a damning assessment of what it means to make art as a group.