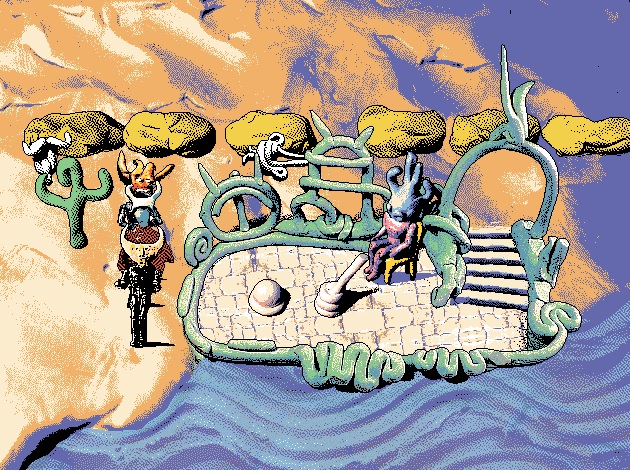

Mason Lindroth has been building up to Hylics for over a year. It’s his biggest project to date, and along the way he’s been breaking off bits of it here and there, releasing them as smaller games. If you’re familiar with his work, you can recognize the ambulant skulls—coppery brain cases hoisted on a nest of tentacles—as they chase you in Hylics, as they were used in Lindroth’s delightfully strange god sim Weird Egg & Crushing Finger.

The more you explore the world of Hylics, the more you’ll see where an idea, a sub-area, or a monster has manifested elsewhere in his oeuvre. But this doesn’t frequent to the point that it feels constructed from smaller parts that don’t congeal as a whole. Quite the opposite: Hylics is Lindroth’s work coming together under a single structure and philosophy, and it’s all centered on his signature use of clay.

In Hylics, mostly everything is made of clay, and if it’s not then it’s usually still in some way malleable. Trashcans are accidentally crushed when searched; juice boxes are drank from a straw until they’re empty and then implode; vegetables are picked, consumed, and then regrow. This is one of the game’s major themes: the reshaping, destroying, and creating of objects from materials. This is why a dying fish tells you that you can make sandcastles a little higher up on the beach it lies on. You take the damp sediment and form it as ramparts and parapets to mimic the techniques Lindroth applies to his creations. You can make a little city if you wish but you can also run through it and kick it all down just as easy. This sandy playground acts as a synecdoche for everything Hylics is implicitly about.

Flesh is the most significant of the materials in Hylics. It’s treated almost as a currency for one’s own life despite it being no less fragile than the sandcastles. When you take damage in Hylics you lose flesh (instead of, say, health). When you rest you restore your flesh entirely. And should you die, you have to watch as main character Wayne endures all the yellow flesh on his face melting away, leaving just a crescent skull. But he doesn’t die, not really, nor do you lose progress, you simply appear in a hub world from where you can warp back to a previously reached area marked by a floating crystal.

While it seems odd at first, not dying and not having to load up a previous save, it makes sense within the grander themes of Hylics. The title itself acts as a big signpost to what these themes are. Hylics is a word derived from the ancient Gnostic belief system and refers to the body. In particular, it describes the body in its relation to the three types of human the Gnostics saw, the other two being psychics (spirits inside the body) and pneumatics (spirits free of materiality). The body was considered the most inferior of these three types. As such, the Gnostics believed that to be material, or of the material world, was the lowest form of being, and so would strive towards a spiritual existence by becoming enlightened through the acquisition of knowledge.

This journey to leave one’s body behind is seemingly at the heart of Hylics although it is never spelled out. In fact, Lindroth admitted to me that the text in Hylics is deliberately misleading. “Hylics has a familiar RPG structure, but instead of exposition, the game has semi-randomly generated text,” he told me. “The player’s goals are communicated visually, by the environment design, so I felt free to make the textual aspects of the game into a sort of joke or red herring. Everything else is there to present a certain atmosphere.”

The RPG structure is key to making Hylics work. Lindroth relies on it so that we intuitively understand that to progress we may need a certain item, or to defeat a particular enemy, or venture into an as-of-yet uncharted area. In short, the game’s ties to the genre are there only to spur on our curiosity. Piecing together this RPG structure was a matter of just that: Lindroth grabbing the world maps from one of his games, the third-person navigation from another, and mushing it together as you would separate pieces of clay into a single ball. But his previous games didn’t cover all the other expected elements that comes with an RPG and so Lindroth admits he was “curious” as to how he’d personally handle those.

The most alien of these RPG elements to Lindroth’s work are the turn-based battles. These have a very rigid structure without too much room for expression without dropping the format altogether. That said, Lindroth certainly makes the battles both enjoyable and recognizably of his own making. He tells me that he finds “battles useful as tools for pacing, and as a means of displaying interesting graphics,” and so that’s what he focused on for Hylics, as well as avoiding the illusion of challenge. What we get are some of Lindroth’s most wonderful animation so far.

All standard attacks are issued with a hand arriving on-screen and making a click between the thumb and middle finger. Your character could be wielding a gun or a club but this attack remains the same. While there’s something satisfying and almost cute about this attack animation the reason for its ubiquity is purely due to Hylics being a one-man project. You can glean this from Lindroth’s explanation of his process to me: “I photograph objects against a greenscreen, and then adjust some sliders in Photoshop. Pixel art is sometimes thought of as a laborious process so it’s fun to quickly fake it. I also incorporate some 3D models and hand drawing; keeping the resolution low makes compositing easy.”

Special attacks are given a little more love. Often, they see the single hand of the standard attack joined by its opposite, molding bits of clay between forefingers, casting books made of minced meat at enemies, or unraveling clay into esoteric patterns. Using items during battles is just as entertaining as they are destroyed in whatever way is appropriate. The most dramatic of these is the stick of dynamite which, once thrown, explodes with the force of a nuclear warhead going off. These animations all manage to be playful—sometimes humorous—in a way that most other battle systems in RPGs never get close to approaching. But they also feed into the focus on physicality and ductility throughout the game.

However, while Hylics (and, indeed, most of Lindroth’s work) may in some way be inspired by the Gnostics worldview, its animations and art almost seem diametrically opposite to it. For Lindroth has always celebrated the materials of the world we live in rather than scorned them. He shares his own fascination with the process of creation with these materials through his games: hands molding substances feature a lot, sand and clay always, and he often illustrates death as a dramatically beautiful breakdown of muscle and bone. To play a Mason Lindroth game is to delight in all that is possible within the material world and to learn how wonderful creation and destruction can be.

Hylics will be coming out in August. Follow Mason Lindroth’s Tumblr page for updates on his work.