Earlier this year, eight-year-old Jivan Armen logged onto a Minecraft server in his home in east Vancouver to start building something new, as millions of his peers do each day. Jivan loves roller coasters and had begun constructing one to transport sheep throughout his world. Then disaster struck.

A griefer logged on and set his roller coaster ablaze. There was no recourse; only tears. Jivan ran to his father for consolation. “It’s not a great introduction to the Internet,” Jivan’s 46-year-old father Haig says. In fact, since then, Jivan has been shy to log into his favorite game out of fear of abuse.

Later, on the 10-minute walk to school, Haig shared the experience with other parents, many of whom echoed poor Jiven’s tragedy. “They all said that inevitably some jerk gets on their child’s server and ruins everything,” Haig says. Fortunately, for Jiven and the children of Vancouver, Haig Armen has a solution.

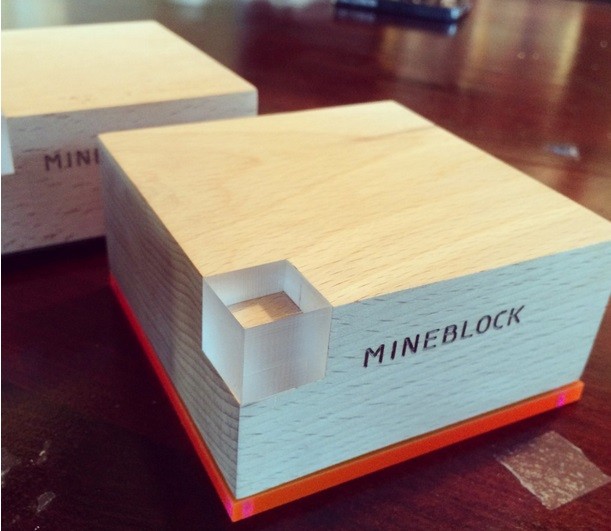

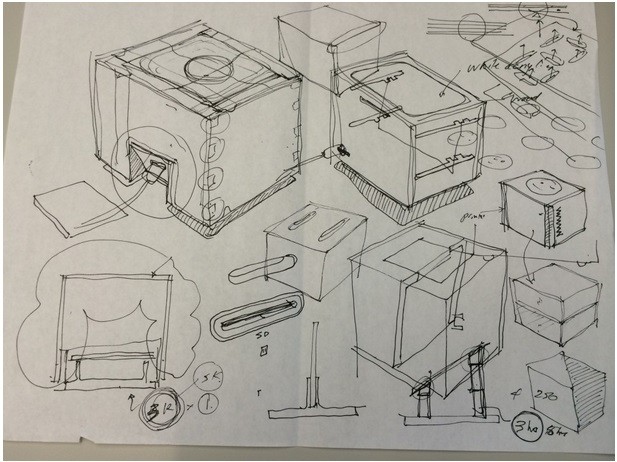

About a year and a half ago, Haig began working on an ingenious device called the Mineblock. A physical object powered by the credit card-sized Raspberry Pi computer and not much larger than your hand, the Mineblock does just one thing: run a private Minecraft server.

To convince reticent parents, Haig valued ease over functionality. “I didn’t want it to look like a computer,” he says. You simply plug it in and Mineblock creates its own wi-fi network. Parents simple connect to it and add it as a server for up to eight different players to enjoy. There’s no concern about griefers invading the party or that tech-illiterate parents would struggle to get it up and running. Armen says that Mineblock is plug-and-play. It will even have a battery pack so parents can take their servers in the car or to the park. “I just saw this amazing opportunity,” Haig says.

So why a physical object? Why not a web-based hosting service targeted at parents instead? Part of the rationale is his practice. Haig runs a small interaction design firm called LiFt Studios and teaches design and dynamic media at Emily Carr University, so he was just practicing what he preaches.

But after attending a conference called Solid, Haig was enraptured by the concept of “the internet of things,” small connected devices that may only do a single thing. “I like the idea of physical and digital merging, of intelligence embedded in an object,” Haig says. Not to mention, one can easily see this being a staple at Minecraft parties such as the three that Haig has already hosted for his two kids. Moreover, it’s easier for parents to simply take Mineblock away if things go awry. “It’s not some thing that’s just out in the cloud,” he says.

Griefing is a problem across a wide variety of internet communities, and no one’s figured out exactly how to keep people from misbehaving. But just as tools like Block Together help Twitter users do the policing that Twitter won’t do itself, Mineblock fixes a very specific need for parents that Mojang, Minecraft‘s creators, have been loathe to do themselves. Haig says parents are drawn to the open collaboration skills that Minecraftengenders, but want a safe space for their kids to explore without their handiwork being damaged.

At the moment, Mineblock is still a patent-pending prototype, but Haig plans to take it to Kickstarter in the near future. He hopes to raise enough money to create 500 units, but it’s hard to imagine that being a problem. For now, Armen will stay busy at his crafting table.