In 1990, on the hundredth anniversary of Vincent van Gogh’s death, the Journal of the American Medical Association posited that the impressionist had suffered from “Ménière’s disease and not epilepsy.” A disorder of the inner ear, Ménière’s disease is known to cause nausea, hearing troubles, tinnitus, and vertigo.

The JAMA’s diagnosis is widely disputed, but Mac Cauley’s VR tribute to Van Gogh, The Night Café, does little to downplay the idea that the artist suffered from vertigo. This may or may not be intentional. As I noted when previewing the interactive experience in May, Cauley set out to transform Van Gogh’s Le Café de nuit into a 3D space. The environment, which Van Gogh modeled on Arles’ Café de la Gare, can now be traversed by anyone in possession of a VR headset.

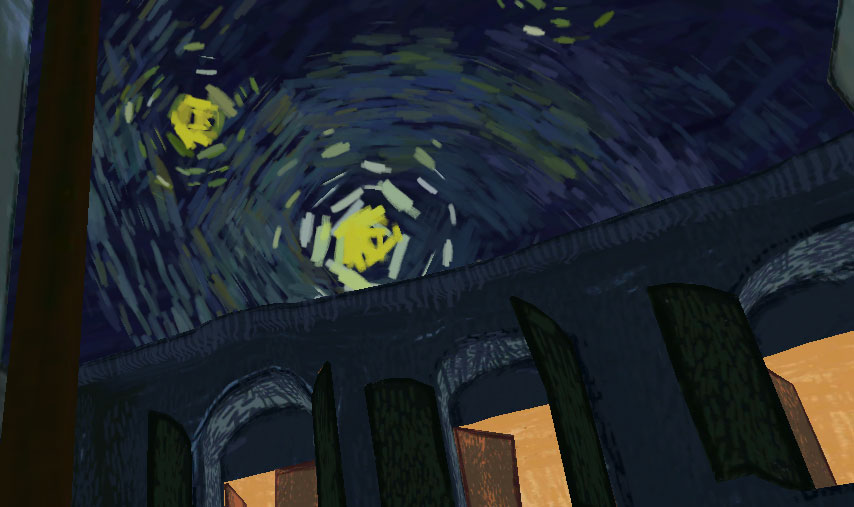

That’s exactly what I set out to do last Sunday, when the Kaleidoscope VR Film Festival brought The Night Café to Toronto, and the results were mixed. Cauley’s work is undeniably visually compelling. It unspools enough of Van Gogh’s swirls to make spaces navigable, but allows smaller features like rays of light to radiate through the air with all the weight of a heavy fog.

Each frame of The Night Café is a painting in its own right, but good luck navigating from one frame to the next. Cauley uses VR to achieve a hifalutin form of point-and-click. You aim by looking where you want to go and then move in that direction by applying pressure to a trackpad. (Kaleidoscope’s festival uses headsets with built-in trackpads. I can’t speak to how The Night Café works in other configurations.) This system is as straightforward as it is imprecise. It requires the user to move her head with unnatural precision. VR encourages you to take the periphery of your vision as seriously as its centre, but The Night Café’s navigation system requires you to only think about what is straight in front of you. Add to this the fact that you can only move at a constant speed, and much of your time in The Night Café is likely to be spent trapped in corners and crashing into walls.

The Night Café is therefore a nauseating experience, but in the brief moments before vertigo sets in, it is profoundly compelling. Therein lies the appeal of the JAMA’s interpretation of Van Gogh’s medical history. I’d like to believe the vertigo is intentional. I’d like to believe that The Night Café’s navigation is an attempt to get into the artist’s mind as opposed to a reflection of VR’s current shortcomings. I don’t really believe those things, but I cling to that hope because The Night Café deserves recognition. In the brief moments where Cauley’s work does not induce nausea, it extrapolates Van Gogh’s brushstrokes in a manner any lover of art would surely appreciate.