Near Death begins when a woman crashes at the abandoned Sutro Station in the Marie Byrd Land region of Antarctica. There is no ceremonious setup, only the bare-bones facts of her situation: the temperature, the location, the condition of polar night, and the wind chill. She fumbles through the dark with the dim glow of a flashlight before finding one of the buildings of Sutro Station and uses a small personal heater to circulate warmth. Her situation only worsens as her contact cannot extract her in extreme conditions, and she resolves to find some way to survive or escape before the frigid dark engulfs her like it did the outpost. It’s a survival tale at its meanest, most basic core. There is nothing but the slow crawl forward a few glimmers of respite. Unfortunately, that meanness strips away any substance or depth to be found in the struggle for survival.

As the sophomore effort from Kent Hudson and Orthogonal Games, Near Death cannot escape comparison to the team’s previous game, The Novelist (2013). In The Novelist, the player haunts the summer home where a writer and his family retreat, unaware of how the player influences their delicate family dynamic. It’s a quiet game that, despite a somewhat narrow focus on the titular character, explores the complex relationships involved in keeping a family together. Limiting the player’s movement options makes The Novelist, at times, uncomfortably voyeuristic and helplessly bleak; even when the characters do connect with each other, someone’s wants are always lost. Combing the thoughts and writings of the family gives the player an intimate perspective into each character, resulting in a troubling and honest picture of a family haunting the same space.

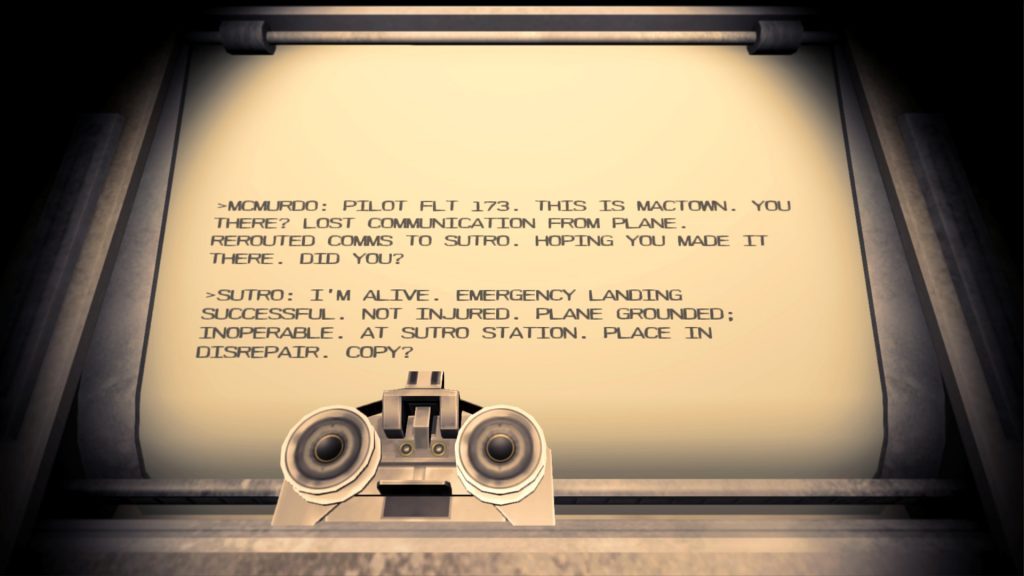

Whereas The Novelist minimized the player’s ability to explore the house and interact with its characters to maximize the impact of an intimate story, Near Death attempts the opposite—forgoing character drama for a story about the methods and means of survival. That is, Near Death’s narrative drama builds from the arduous tasks required for the protagonist’s survival. Her only contact communicates to her through a teletype, and, though there is enough banter to give the illusion of a character behind that antiquated tech, neither he nor the protagonist becomes anything more than what they do. Actions are the story in its entirety.

Near Death, then, becomes a survival game at its absolute purest. Others in its genre—The Flame in the Flood, Alien Isolation (2014), Don’t Starve (2013), Rust (2013), Miasmata (2012), etc.—all contain something other than the natural elements (a monster, a noticeable art style, a death-and-rebirth feedback loop) to trouble the player as she fights to survive in hostile environments. Near Death, however, has no hook or narrative invention to propel its protagonist forward other than the primal need to stay alive. As a result, she and her contact, despite a few jokes between them, seem hollow and under-developed. If some other part of her character, some existential force other than my directing her with a mouse and keyboard, occupies her mind and drives her toward home, I never learned about it.

This hollowness of character echoes in the empty Sutro Station as well. Aside from a breakroom that contains a pool table and an eerily functional jukebox, nothing about it seems like it was ever inhabited. Traces of human life have all been buried under ice and snow, and while the wilds of Antarctica should maintain a distinctness in the game, the station just seems like another version of an empty house or abandoned outpost I have explored time and time again in recent memory. There may be some lesson here, a sort of Conradian observation about the futility of our desire to tame the dark parts of the world. If so, then it forgets the human element that makes such moral tales resonate. Instead of tension, there’s boredom; instead of revelation, I met another task to complete. For most of the time I spent in Sutro Station, I felt bored, encumbered by the slog from point to point until I could finally leave.

Part of me thinks this feeling of boredom is by design. After all, it is only because I had nothing else to do that I thought meticulously how to move from one section of the station to the next. I looked at the very basic map I found, planned my routes with poles and guiding ropes to anchor my path, set down beacons to serve as guide markers, and took careful stock of the battery life of the flashlight as I sent her stumbling into the dark polar night. I began to notice how the portable kerosene heater worked best in small spaces and found ways to create small pockets in the station to generate a quick burst of warmth before moving to the next objective. Despite its emptiness, I grew somewhat attached to the station that held me hostage as often as it provided respite.

On a couple of occasions, I even ventured out in the snow with the distinct goal of becoming hopelessly lost, and after what felt like a few feet, I turned around and lost sight of the station. The terror of being swallowed by the darkness outside is, perhaps, the game’s greatest quality. It happens suddenly and convincingly after misjudging distance or losing a guiding light through the thickness of the storm that panic causes a sequence of bad judgments that result in freezing to death. Trudging through the oppressive dark and scrambling to patch up broken windows to create a makeshift shelter for heat provides moments of genuine triumph, as long as conquering sections of the landscape can serve as its own reward.

In those moments, Near Death succeeds in eliciting a sigh of relief at finding a moment to breathe in a place hostile to comfort, and, thankfully, the game’s smart pacing means it does not overstay its welcome. Such tension, after all, is no more sustainable than the station at the game’s center. Ultimately, though, Near Death has nothing to say beyond the struggle to navigate the harshest environment on Earth. Perhaps that’s enough, that the story of survival isn’t about conquering the environment but finding a way out. But with the way in which The Novelist uses its conceit of voyeurism and spectral suggestion to tell a story of family drama, I hoped that the minds at Orthogonal had something more thematically ambitious woven into Near Death. Instead, it mostly feels cold and barren.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.