When I was born late into 1990, the Super Nintendo had already been released in its home country of Japan. Over here in the States, Super Mario Bros. (1985) had already been entertaining my parents for years. Pong (1972) had entertained my pastor, and Tron (1982) had already hit theaters to the collective “meh” of audiences worldwide. As such, I have only ever known a world with videogames. But it’s worth pointing out that, relative to text or music or even film, videogames are still a fairly new medium. And as with any new medium, its invention has lead critics and academics to develop new language for discussing it.

Take terms like “ludonarrative dissonance,” which describes the disconnect players feel when their actions in a game don’t match up with the story being presented to them. The term was only first proposed in a 2007 blog post on the then newly-released BioShock, and even taking into account prior discussions on the topic that did not directly use it, most only date back to the early 2000s at the oldest. This does not necessarily make the term incorrect or a poor representation of the topic it’s discussing, but it does mean that there is still time before it is taken as general knowledge for others to present alternative terms that might be able to better represent the idea, or to discuss if the issue raised by ludonarrative dissonance is even much of a problem in the first place.

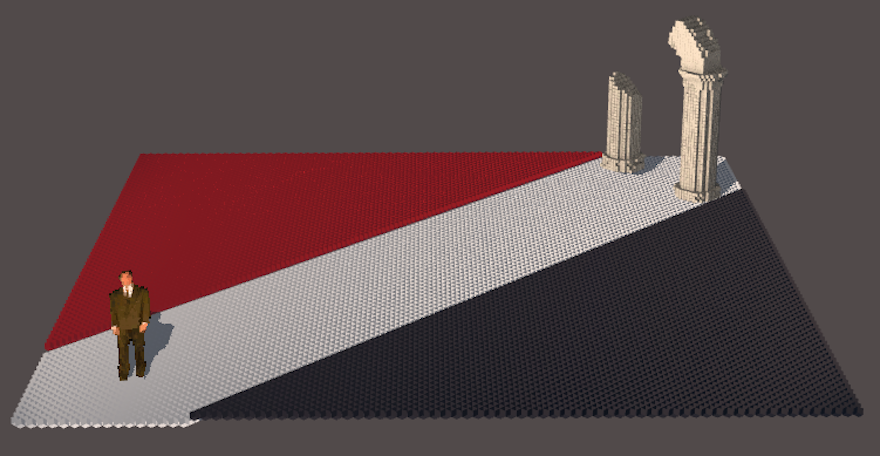

In their new game Game Studies, Pippin Barr of games like last year’s Best Chess and Jostle Parent, and Jonathan Lessard of games like 2014’s A Tough Sell and this year’s Rogue Solitaire, call some of of gaming academia’s most prominent truisms into question. A series of five short levels, the game is simple: get the man to the goal by clicking on the ground until he walks there. Along the course of each level, the game will lampoon one of five different theories, whether by having the player dive into a pool to demonstrate “immersion,” having them walk into a circle to demonstrate “the magic circle,” having them play baseball while listening to Snow White to demonstrate the conflict between “ludology and narratology,” and the like.

Notable among all these levels seems to be a general insistence that perhaps gaming academia is being a touch obtuse and generous in their discussion of these topics. For instance, while popular flow theory advocate Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi might argue that “flow” in a game is a special state of hyper awareness and enjoyment, Game Studies presents it as more of a tool of manipulation, just a simple method for getting the player to stay on a prescribed path rather than challenging the developer’s intentions. The same applies to Game Studies‘ depiction of the “magic circle,” or the thought that virtual worlds should provide an escape for the player and insulate them from reality. While this could perhaps be compared to the theatrical tradition of suspending one’s disbelief while watching a show, Game Studies presents it as more of a shallow constraint that anything else—step from a larger outside space into the more constrained circle and you get fireworks. Yay you! Not much else to do when you get there, though.

“While the academics sit in their ivory towers thinking about postmodernism,” writes Barr in the game’s factsheet, “Game Studies will be out there in the trenches, educating the public on the theory of games through the most painfully obvious physical metaphors for game studies concepts we could come up with.” He then goes on to discuss that, jokes aside, the idea behind Game Studies was to interrogate the question of whether games can be used as educational tools at all, or if trying to take difficult, abstract concepts and teach them using aesthetically-pleasing, fun systems of play dilutes the ideas a bit. Like the rest of the game, this questions another popular topic in game studies—gamification.

For instance, if a game is tailor-made to please the player, then can they learn the material, or does the lack of academic challenge mean that they are simply repeating the steps intended by the designer without considering what is being taught? For an extra bit of meta, Barr and Lessard then decided that the best way to pose this question would be to try to use a game to teach players about game studies itself, and seeing if they leave understanding it better or, rather, if they feel like they’ve been patronized to.

The game is available to play for free over on Barr’s site, and the end credits contains a full list of the references Barr and Lessard used while making it. While the game can be breezed through in roughly 10 minutes, reading through the sources will obviously take longer. But doing both raises the question: can a game teach someone about an extrinsic topic like academic theory—and can it succeed in making that learning process fun—or are you better off just sticking to the original text?

To play Game Studies for yourself, visit its website. To keep up with the rest of Barr’s work, follow his Twitter.