Take a short walk around the streets of Ha Noi, and it’s easy to come across pockets of French influence: grandiose colonial architecture, pâté-filled baguettes, bars with names like ‘Eté’. Unlike francophone West Africa, however, there’s little else to suggest the 52 years it spent as colonial capital of L’Indochine Françoise. Perhaps this is because the expulsion of the French is synonymous with the birth of modern Vietnamese nationalism, or because of the aloof nature in which the area was governed. Either way, the most profound impact that colonial rule still has on the contemporary culture of Vietnam is through the introduction of a sport that very quickly turned into an obsession: football.

I came to be in Ha Noi completely by accident. My girlfriend and I had just been denied work visas for Japan, on Christmas Eve no less, despite a clean record and job contracts. We’d already booked flights, and were determined to visit, even if only as tourists, but needed a follow-on destination, and fast. Almost immediately, it was Vietnam; we had friends there, who assured us that plentiful jobs for Tays (foreigners) and the extremely cheap cost of living meant it wasn’t much of a risk. Buoyed by their confidence and driven by the desire to make our first overseas sojourn more than just a holiday, we arrived six weeks later.

While it was easy to find work and housing, attempting to integrate and get to know our Hanoian neighbours proved far more difficult. As an intensely tonal language, Vietnamese is notoriously difficult to learn; even the slightest mispronunciation can render the most basic request into nonsense, often providing hilarity for native speakers. Thankfully, there was a global language, one that didn’t require perfect grammar or accurate pronunciation, begging to be used.

It quickly became apparent that If I wanted a quick way to engage with unwilling teens sent to my poorly-ventilated classroom by eager parents, or to defuse stares sent my way due to being the only white guy in the local bia hoi, it would help to know a little about European football leagues, or at least pretend to. The simple fact of being Caucasian seemed to confer upon me the status of assumed expert, and it was gratifying for my ego to play along, especially when the locals took me for an idiot most of the rest of the time. When talking about football, otherwise shy students and heretofore strangers were transformed into eloquent students of the game, easily outshining my knowledge while expounding on the virtues of any number of EPL, La Liga, Bundesliga or Serie A players and teams.

It didn’t matter that my ‘favourite’ team was chosen as a child because I liked the deep blue of their playing strip; many of the people I spoke with had chosen their teams for similarly arbitrary reasons. More importantly, we had something to talk about in our improvised, mediated language, one full of phrases cribbed from sportscasters and those vague physical gestures that somehow manage to express agreement and enthusiasm, no matter where you are.

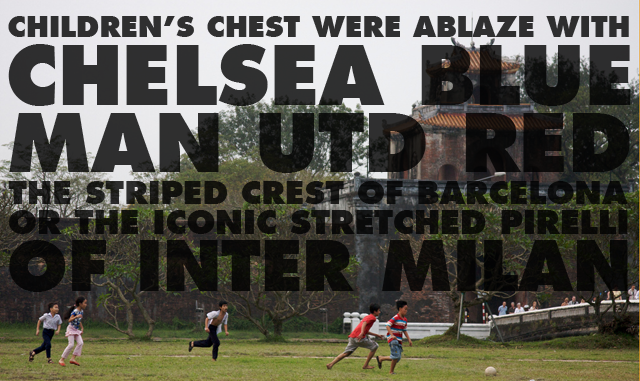

On the streets and in schoolyards, children’s chests were ablaze with Chelsea blue, Man Utd red, the striped crest of Barcelona, or the iconic stretched Pirelli of Inter Milan. It helps that these euphemistically-titled ‘replicas’ are obtainable for the cost of a coffee from Starbucks.

What you were much less likely to see was anyone wearing the kit of Ha Noi T&T or Xuan Thanh Sai Gon, or to hear of much enthusiasm shown when the subject of the local V-League comes up. Many fans just didn’t seem to be interested in it, perhaps due to its relative lack of quality and the fact that with the internet it is just as easy to watch the much more attractive European games. In fact, while you might expect the streets of such a football-mad place to be rife with cheeky kids passing a ball around on the way to practice, or makeshift games taking place in idle alleyways, you could easily spend several weeks in Ha Noi and see everything related to football except the beautiful game itself.

For starters, there is simply nowhere near enough open space or resources in Ha Noi for the majority of people to get the chance to play regularly. Empty sidewalk basically doesn’t exist. Parks are scarce and largely composed of concrete and water features, and although you might see a few enterprising kids playing keepy-uppy in a disused spot, there definitely isn’t enough room for much of a game. While one of the gated international schools, off-limits for all but the very privileged few, might boast one or two sports fields, many of the schools I saw were only equipped with something resembling a courtyard. Sometimes these areas had a few playground facilities, but usually they were clogged with clusters of padlocked-together scooters; either way, they weren’t well suited for kicking a ball around.

That’s not to say it’s impossible: organisations like Football For All in Vietnam (FFAV) are doing great work providing equipment and playing space for kids to use. Often, though, playing fantasies are acted out in quite the opposite sort of location: badly lit basements and converted living rooms down improbable alleyways and tucked behind shops, although always within range of a good parking spot. Just as football fandom in Vietnam is imbibed on screens, so it is on them reproduced: within the frenzied confines of a PlayStation 3 den.

One afternoon, a student of mine, Binh, convinces me to let us finish class a little early and head to an arcade near the school. Mid-summer tropical heat doesn’t make a four-hour private tutoring session on grammar particularly fun for either teacher or student, no matter how much you feel you’re finally making headway on the present perfect continuous. The weather is a classic July special, an infuriating mix of rain and heat that leaves two options: either get drenched or boil alive in a poncho.

I choose the latter and am relieved when the journey to the arcade only lasts a couple of minutes and we quickly turn into a nondescript block of buildings, with the only clue of their contents a well-worn plastic sign bearing the acronyms “PS3 – PES – FIFA”. After negotiating a park space we are guided into a characteristically grey cinderblock of a building and led down a hallway. What we find at the end is a large room equipped with enough shiny technology to rival the GDP of the rest of the block.

At least 20 latest-model flat screens adorn the otherwise empty walls, each uniformly joined by a PS3 and matching black pleather couch. Despite all the flashy tech, it only costs about $US1 for an hour’s play. Questionable economics aside, in a country where $US300 a month is considered a phenomenal salary, it’s the only way many would ever get the chance to hold a controller in their hands. Right now, the couches are filled with pairs of young Vietnamese men with an average age of around 20, engaging in what seems like life or death games of virtual football. Eagerly, we sit down at the nearest free console and join in.

As a decidedly amateur FIFA player, playing the unfamiliar PES, I am somewhat out of my depth. There are no Quick Play options here: each player is afforded as long as they need to agonise over line-ups, formations, tactics. It doesn’t seem bad form to abruptly halt play several times a game to tweak one’s squad, and there is a mutual respect (and even nodding approval) of an opponent’s need for his team to be at their absolute best possible combination. Attempting to shield my pride as much as possible, I choose Barcelona, pretend to agonise over my squad for a while, and am then promptly thrashed several times. It seems appropriate.

The academic intensity of pre-game fine-tuning is contrasted with the sheer emotional outburst delivered at the scoring of a goal: simply put, it’s clear that winning (and losing) a game has real meaning for these players, beyond mere arcade superiority. For many gamers, sports sims are about extending and perfecting skills we wish we had in real life, living out dreams that were at least theoretically possible in our youth; generally, if we have the sort of income to be owning a console in the first place, we can expect to put down the controller, leave the house and gain access to facilities to engage in the sport in real life.

In Ha Noi, these opportunities don’t exist for the majority of players, so it makes sense that they’d throw themselves wholeheartedly into the next best thing. One suspects that the online leaderboards for FIFA and PES would be dominated by Vietnamese players if they weren’t playing pirated games on heavily modded hardware. On subsequent visits with Binh, it became more fun for me just to sit back after a token game or two and watch them perform. They were that good.

Sitting there, trading jokes and ‘friendly tips’ with fellow gamers, members of the new generation of Vietnamese raised increasingly on outside culture, it was easy to forget where I was. It felt like home.