On Wednesday, Land Rover released a British suspense multi-sensory short story on Tumblr that rocked my world in all sorts of unexpected ways. And I don’t know how to feel about it.

Written by 62-year-old native author William Boyd, praised for his recent 2013 Bond continuation novel Solo, the conspiracy thriller follows the journey of struggling C-list actor Alec Dunbar. Feeling financially uncertain after another dud audition, Dunbar accepts an off-handed offer to make a trivial delivery to Scotland for a hefty sum of money. After being given a “weather-battered” Land Rover Defender for transportation for the delivery, the unsuspecting actor sets off on a journey of mystery, intrigue, and rugged terrains in the hinterlands.

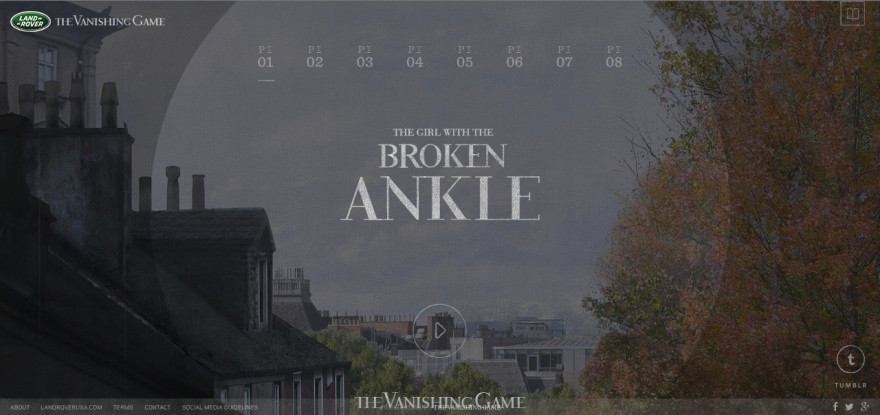

The project combines the dulcet tones of an excellent British voice actor with automatically scrolling text that coincides with video, photography, animation, sound, and music. Stunned into silence doesn’t even begin to cover it. The Vanishing Game is the first time I ever witnessed a soundtrack be put to digital literature so effectively. The subtly suspenseful score lands all of Boyd’s best moments, and his experience as a screenwriter shines through seamlessly with the videos and visualizations. All the main moving parts, performed masterfully by both narrator and author, take their rightful place center stage, while the multi-sensory queues usually remain as unobtrusive supplements.

Now, don’t get me wrong. There’s also a lot of times when The Vanishing Game falters. Hard. As in falling flat on its stupidly obvious face. Every now and again, a word like “water” or “snow” will be hyperlinked and, when clicked, redirects the reader to “real stories” from “real social media Land Rover owners” all gushing about their unending love for the vehicle using the #WellStoried hashtag. This narrative undoubtedly suffers from the advertisers grabby pull for “interactivity” by adding these clickable links which actually manage to ruin flow and immersion. After clicking on one of them accidentally, and interrupting one of the most sumptuously eerie moments in the story, I felt almost violated. Like I needed to take a shower to wipe the stench of money off me.

“We gave him free reign to tell the story he wanted and feature any Land Rover vehicle he wanted,” defends creative director of the advertising agency Y&R, Marc Sobier. “This makes it more of a true commission, rather than product placement or sponsorship. If an artist’s freedom is respected, I think these types of projects would be more appealing to them.”

I certainly don’t judge any writer who takes sponsored work—and if I did, I’d either be a huge hypocrite or just horribly naive and arrogant about any writer’s ability to survive without sponsored work. But it does feel undignified for the work and form at times. Especially because that damned Land Rover logo hovers so boldly in the top lefthand corner, never even fading into an unobtrusive watermark.

But Boyd also seems genuine in his excitement over the project. “One of the collateral pleasures of writing The Vanishing Game was that it made me realize how prominently Land Rover has featured in my life—in Africa and Britain—to an almost mythic degree,” he said in a statement. “I remember as a boy being driven in a Land Rover through tropical rain forest to the Volta River in Ghana to fish for freshwater barracuda. And, as an even younger boy, climbing into my Uncle Ronnie’s Land Rover, the Scottish day dawning, as we went out to feed the sheep on his farm. A Land Rover is part of the mental geography of almost every British person, I believe. Consequently, to be asked to write a story in which a Land Rover features was immensely appealing, almost an act of homage.”

Listen, I’m pretty proud of Land Rover myself (and I’m sure as the multimillion dollar company cares a lot about my opinion). They commissioned this innovative blend of new and unestablished storytelling with no guarantee of whether the stunt would be lucrative or not. They took a chance on a quite a nuanced and relatively unknown form of digital storytelling. That’s scary stuff for an advertising campaign. And to be honest, Land Rover seems to have demonstrated a much bigger faith in the future of digital storytelling than most of the world’s biggest publishing companies, who generally continue to reject innovations in literature and only reluctantly change when it becomes absolutely necessary.

And while the literary crowd is one that tends to turn its nose up (if not outright gag) at words like “sponsored literature,” there’s also something to be said for the historical relationship between marketing and literature. For one, we often forget the fact that classic novels like Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the D’urbervilles was written and published as a serialized periodical. When you think about it, the invention of serial literature in the seventeenth century was little more than a marketing ploy, to expand the audience base which would lead to more dough. Without a doubt, the serialized format affected the narratives of these stories. In fact, one of Hardy’s earlier stories even coined the term “cliffhanger,” since one of the acts (or “episodes”) literally left a character hanging off of a cliff. With a dramatic structure mimicking the more theatrical approach of Greek tragedy, serialized novels tend to stick closely to Freytag’s plot pyramid. As a marketing tool, or as a way to entertain the enormous audience of Greek and Elizabethan theater-goes, this more archetypal type storytelling casts a wide net, reaching a lot of people.

Would Tess of the D’urbervilles have been “better literature” if Hardy hadn’t felt the need to end each chapter in a bit of suspense to sell more magazines and make more money? The world will never know. But there’s no denying that the literature, regardless of what kind of marketing tactics it answered to, is still high-quality.

Of course, what Land Rover has done—commissioning an author for blatant product-placement—is a different beast than serialized literature. But as Boyd told ABC News, “They said they wanted an adventure and they said, ‘Somewhere in this adventure it would be good if a Land Rover appeared.’ But it was left entirely to me the extent I concentrated on that or made it fleeing and passing.”

Though at times references to the Land Rover in the story (lovingly called KT-99 due to a number code stenciled onto its side) can get a bit overindulgent. And you have to imagine how the editing process might change when its done to please an advertising company. But I mostly believe that Boyd decided to feature the Defender so prominently out of a genuine love for and inspiration from the brand. “What I tried to achieve was to make the Land Rover an inherent presence in the story, something always there—implicit, strong, solid, reliable, ready to function—very like the part it plays in my memory,” Boyd continues in his statement. “Welcome to an icon of motor vehicle history.”

The Vanishing Game’s eight-part story, aside from being available through an impressive customized Tumblr page, is also available as a free eBook on Apple’s iBooks Store (iPad and Mac), and the Kindle Store (either on your Kindle or through the Kindle app for Android, iOS, PC, Mac.”