Some people say the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results. But I just call that playing a videogame. Or being young.

Peter Padder Pauleypop, a short game submitted to Ludum Dare 31 this past week, explores that tortured but somehow beautiful repetition which so defines the medium. And how crazy we all are for loving it. Inspired by the fishing sequence in the 16-bit gem of a Final Fantasy game Illusion of Gaia, the game labors over the isolating monotony of floating adrift in a sea of tedium. As one of Illusion of Gaia’s more hated scenes, the fishing sequence left players stranded on a raft in the middle of an ocean, forcing them to play through several in-game days of the same exact routine. You spoke to your lady friend, futzed about, and then caught fish. Over and over and over again. Day after day. In order to progress, you must catch enough fish, which by the end feels like feeding the demon that is the game system rather than sustaining your character.

A succinct summary like that doesn’t even come close to capturing the seemingly endless minutes many players wasted on that raft, though. You could only wait, until a couple of poor guppies come along to sacrifice themselves. Peter Padder Pauleypop, though a self-declared love letter from creator Richie Hoagland to the SNES Final Fantasy games, distills that immense, fruitless frustration. But it also reads like homage: an anguished love letter, perhaps, to your first significant other who you once adored as a young’un but who now just seems like a giant waste of time.

“I live off the broken machinations of a childhood,” are the first words ever spoken inside the world of Peter Padder Pauleypop.

You begin the game with your avatar, an amorphous blob, siting hunched with dangling feet off the ledge of a cliff. He looks tired, alone, resigned.

The environment is sparse, mostly white washed with some pencil-scratched shadows. As you first get up, the camera zooms out to reveal a sky behind the precariously tall structure you walk on. It recalls something out of Lemony Snicket or Wayside School: an impossible place, glued together only by the power of childhood imagination.

Your avatar shambles back and forth across the screen, zombie-like, mechanically fulfilling his purpose. Eventually it becomes clear that you need fish. No explanation for why, only the assumption that you will follow through with orders because that’s what the game told you to do. So you fish off the side of the cliff, the water indistinguishable from the waves of clouds flowing above.

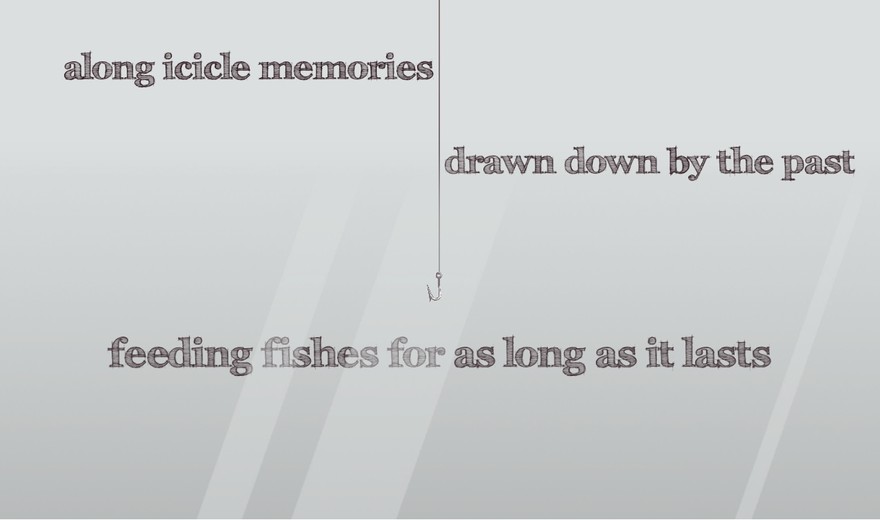

When you catch your fish, Peter Padder Pauleypop robs you of even of the basic pleasure of watching your avatar enjoy the hard-earned prize. Instead, you must get up, shuffle back, and watch the perverse Lemony Snicket structure transform into the stuff of pure nightmares. A black tongue shoots from out of an opening in the structure, wrapping around the fish before darting back in. The top of the building pulsates as the monster’s heart beats, pleased with your offering. Each time you catch another fish, snippets of a poem are revealed, and suddenly you realize it’s the monster speaking—taunting you, and demanding tribute.

Slowly, you start to see the benevolent monster as all the games you spent hours of your early years laboring over. Feed me, the games of childhood had demanded. And you obliged, sustaining them with each repeated, monotonous action taken again and again at the behest of a computer program. Suddenly, the defeat in your one-eyed avatar’s hunched shoulders mimic your own.

Returning to the games of childhood are a weird experience. Once the nostalgia wears off, an inevitable sense of futility creeps in. Is this really the game you logged forty hours with? Without the wonderment of childhood, the environments look dull and juvenile. Mostly, you spend your time in the game catching fish (literally or figuratively.) As an adult, you are robbed of enjoying life’s simple pleasures. Catching in-game fish reminds you of the groceries than need to be bought. You turn off your Nintendo 64 or SNES game, to let it collect more dust in your mind.

By the third fish you catch in Peter Padder Pauleypop, you’re ready to give up. But the game—that pulsating building monster—has already decided that for you, too. “End,” it declares, your avatar staring sightlessly into the sea.

Waste some time with Peter Padder Pauleypop on PC, Mac, and Linux for free here, and follow more of Richie Hoagland’s work through his game studio, Super Soul.