When 3D spaces were popularized in videogames it led to a new kind of energy bubbling up through creative pores. Those who worked within the medium had a whole new avenue to explore—all this extra space, and what to do with it? No longer did illusions have be figured out, but actual working 3D spaces could be furnished and design bent around the new challenges they brought.

Classic architecture such as Doom‘s haunting sci-fi corridors and Resident Evil‘s labyrinthine mansion were invented within this era, becoming archetypes for years to come. It’s typical of Pippin Barr, then, for his first 3D videogame to eschew these grand designs that came before it. It isn’t complex, and it doesn’t have an intricate world to explore or figure out. He has instead vouched for a game about emptiness. Of course he has.

Barr has already made a videogame that is mostly about waiting in line for hours at a time to see Marina Abramovic at the Museum of Modern Art. He has also created an endlessly unwinnable series of games based on Ancient Greek punishments that are best surmised as mini exercises in frustration. So the fact that The Stolen Art Gallery contains exactly zero pieces of art fits easily into his oeuvre.

But Barr didn’t make it this way for consistency’s sake. It was made after he discovered The Museum of Stolen Art, which is a virtual gallery filled only with pieces of art that, yes, have been stolen in the real world. The idea of that project is to restore these treasured but lost pieces back to the public through the use of technology. Barr liked the idea but wanted to riff on it a little. He wanted to make us ask questions.

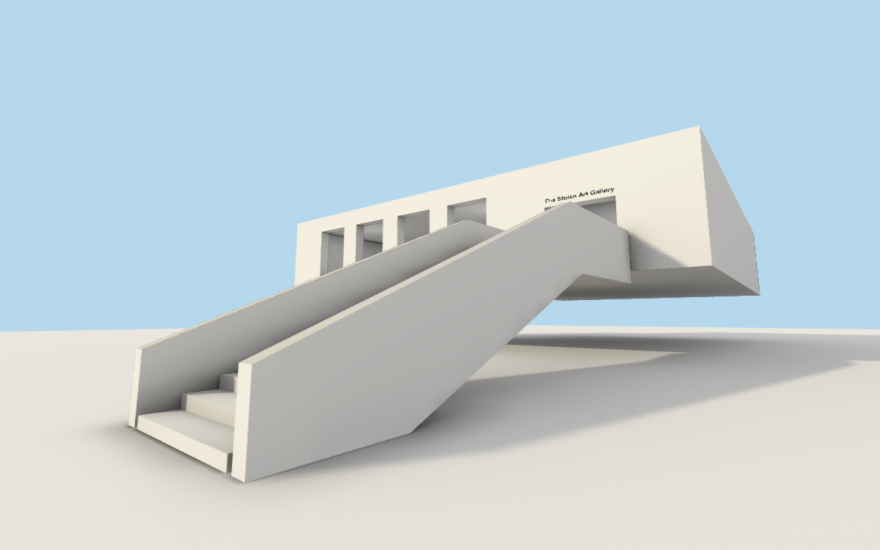

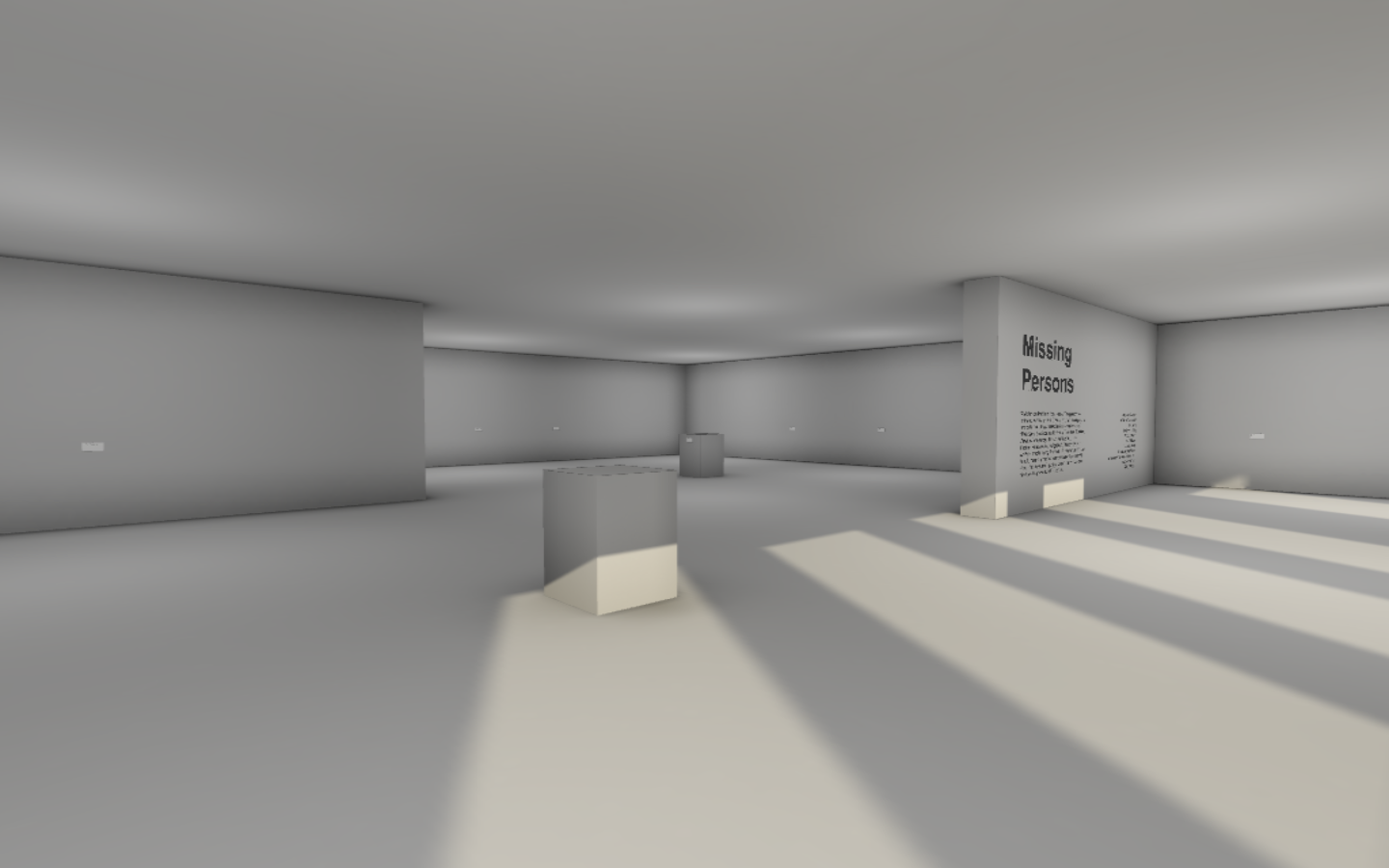

He does this by offering us the space of an art gallery, including the informational tags that describe each art piece, and the plinths that would hoist two of them to an equal height as the images hung upon the walls. It’s an art gallery in everything except its capacity to house any art—an art gallery according to its dimensions and descriptions, but not its contents.

When comparing it to The Museum of Stolen Art, Barr rightly points out that his take is “rather closer to the truth of the matter,” but in a less smug fashion than that reads. His point with this first 3D project (apart from learning 3D game development) is to have us think about “virtual accessibility.” Yes, you can see these stolen artworks in that virtual gallery, but does that resolve the situation? Of course it doesn’t.

Further than this, I think Barr is erring towards having us consider whether the virtual can act as a surrogate or a placebo for matters in the real world. As we become more intimate with and rely more on technology, there comes a point at which we might want to take a moment in order to question how much of our existence we’re substituting for virtual counterparts. Is it a problem that our possessions and experiences are immaterial? To be clear, there are no answers here as art like this exists only to pose questions. Look, here’s another one: is this art or not? Another: is this even a videogame?

You can muse on these matters to yourself while checking out The Stolen Art Gallery.