A baby’s gone and knocked its head off a wall and quit breathing, so Tots and Stephen have to haul ass out to the ambo garage and make for Crazy Horse Housing in eastern Pine Ridge. Worm, an intern doing ride-alongs as she studies to be an EMT, decides to stay behind. It’s probably a pretty dull call, she says. The baby started breathing again, the dispatcher announces, and someone asks if it ever really “stopped breathing-stopped breathing? Or stopped breathing like–” and does an impression of a baby getting its wind knocked out, face panic-stricken but lungs still wheezing thimblefuls of air. So probably it’ll be a pretty dull call, and anyway, Worm promised she’d play this video game with me.[1]

The game is Assassin’s Creed III, and the main character is half-Mohawk—the first Native main character in any big-budget, blockbuster, American movie, television show or video game ever released[2]—and I live on an Indian reservation, the Pine Ridge rez in southwestern South Dakota.

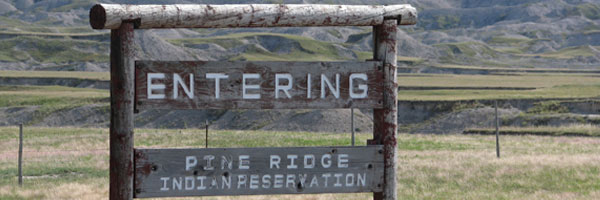

If you’ve heard much of anything about reservations in recent years, there’s a good chance this is the one. It’s the home of the Oglala band of the Lakota tribe, more widely known as the Sioux—which is actually a French-ified version of the Ojibwe name for the Lakota, which may or may not have been an insult meaning “little snakes.” Along with Geronimo’s Apache and maybe Quanah Parker’s Comanche, the Lakota are probably the most famous of the Plains Indians, the tribe of Crazy Horse, Sitting Bull and Red Cloud, of Custer’s Last Stand and the Massacre at Wounded Knee. Dances with Wolves is about the Lakota, and the illegal mining camp of Deadwood—home of the biggest gold strike in history, where the Hearst family made much of its money—is a few hours north of here in the Black Hills that the Lakota fought so long and so hard to save.

In the 1970s, members of the American Indian Movement came to Pine Ridge. Intra-tribal fighting, exacerbated by federal authorities, turned the rez into the most dangerous place in America for much of the decade, with a murder rate nearly twenty-times the national average, and almost nine times higher than Detroit, the most dangerous US city at the time. Peter Matthiessen wrote a history of that peroid called In the Spirit of Crazy Horse, Robert Redford made a documentary about the killing of two FBI agents and subsequent murder conviction of AIM’s Leonard Peltier called Incident at Oglala, and the Val Kilmer movie Thunderheart is based loosely on some of those events.

That, though is all ancient history. Old tensions still simmer now and again, but through a mixture of forgiveness, denial and historical amnesia, the violence of a generation ago is rarely a source of contemporary conflict. Former AIM activists are married to former Federal Marshals. The children of families on both sides of the conflict go to school together, hang out together, have weddings and kids and divorces together.

More recently, you might know Pine Ridge as the go-to spot for mass-media sob stories about the “bleakness” of reservation life. Reporters almost invariably use that word to describe the rez—Google “pine ridge, bleak” for a sampling – and to the outside eye I guess I can see why. The land is violently beautiful—lunar-looking Badlands; rolling prairies, burnt a pale saffron by the sun; scabrous ridges and looming buttes, prickly with cedar trees—but to anyone from the city it just looks variations on a theme of empty. This is one of the poorest counties in America, as most visitors know coming in, so the run-down trailer houses,[3] beat-up “rez-bomb” cars and trash strewn streets do little to dissuade the average reporter from any preconcieved notions of “bleakness.”

And then there are the statistics. The alcohol, drug, unemployment, diabetes, suicide and sexual abuse rates on the reservation are staggering. The average person born in Pine Ridge can expect to live for about a decade less than the average Haitian. Alcohol is illegal on the reservation, but the nearby town of Whiteclay (“Welcome to Nebraska, Home of Arbor Day” a roadsign on the border says) sells somewhere on the order of a few hundred thousand cans of beer per Whiteclay resident. It’s pretty clear where all the booze ends up.

But bleak or beaten down is about the last way you’d describe life around here. The place throbs with a vibrant humor and good cheer that are at once its defining characteristics, and its most ineffable. Tragedy can be captured with a few sad statistics or one of the ugly anecdotes that are never in short supply. That vitality though, the life of the place—in spite of, and yet somehow inextricably linked with, all the death and tragedy—is much harder to see, and harder still to convey.

Even positive stories about the rez sometimes ring false. It’s a wonderful thing whenever someone “makes it,”—going off to a fancy college, becoming a lawyer or doctor in a big city somewhere. The more relevant success story that you never hear about though is that of the average guy, just getting by. He struggles but shows up for work, helps coach his kid’s basketball team, and gets enough enjoyment out of his weekend to wake up Monday morning and do it all again.[4] But even if working moms yawning over their first cup of coffee could apply to be objects of media interest, they probably wouldn’t. It’s a longstanding tradition in the tribe that raising yourself above others, presuming to speak for them or about them, is a bigtime no-no.

This attitude has even rubbed off on me. I’m a white guy from Massachusetts, but I’ve lived here off-and-on for more than eight years, working as a teacher, coach, tutor, skate park overseer, bus driver, and ranch hand, amongst other things. I’ve also worked as a writer and freelance reporter throughout, but this is the first thing I’ve ever written about the rez. I’ve never felt like I understood the place well enough to write something that wasn’t silly or stupid or even harmful to the people around here. But a video game about a Native guy who runs around Boston fighting Redcoats was just too tempting to turn down.

*************************************

Stephen and Tots (short for Ta’teolowan–Wind Song Woman) get back about an hour after they left for the injured-baby call. Over American Spirit menthols[5] outside, they fill Worm in on what she missed.

“Eeez, we got 22’ed off the baby call on the way there for a thirteen-year-old girl who was all lit up at Subway,” says Tots. “She tried to fight the cops and they tazed her and she smoked her head on the floor, blood everywhere. She coded out on the way to the hospital, but we brought her back and now she’s conscious.”

Worm kicks herself for missing all the excitement.

“Jooosssshhhhhh,” Tots says a couple minutes later, “just messing with you.” The baby was fine when they arrived (wind knocked out, as predicted). There was a second call, and it was for a drunk thirteen-year-old girl who was picking fights with the cops at Subway, but no one tazed her (even after she hocked a golf ball-sized, liquor-laden loogie into the face of one cop). Just a crazy drunk girl who proved harder to get into the ambulance than a water bed mattress.

“All dead weight, that one,” Stephen tells Worm. “But you never know what you’re gonna miss when you don’t go out on a call.”

I’m happy Worm didn’t go on the call, though. I’ve needed her back here with me, slogging through the early stages of the game. In an act of apparently industry-shocking subterfuge, the makers of Assassin’s Creed hid the fact that the first third or so of the game is centered not on our half-Mohawk hero, but rather on his absentee father, an impeccably mannered Brit named Haytham Kenway who turns out to be a member of the Templars, the shadowy group that the shadowy, titular Assassins have been battling for centuries. Daddy Issues are a central pre-occupation of the series, both for Haytham’s son, and for the central figure in the game’s modern-day frame narrative, a begrudging Assassin named Desmond, who’s been thrust into a quest to defeat the Templars, make peace with his own Assassin dad, and save the Earth from like, solar flares or something.

The Haytham sub-plot is a fairly interesting one, but thanks to Worm missing all the fake excitement, we’ve managed to zip through most of it to the more relevant parts of the game. I’ve got a story to write, after all, and with Tots and Stephen back, I now have a full team assembled for the first appearance of actual Natives.

It’s Colonial-era Boston and a Redcoat officer has been kidnapping and selling Mohawks as slaves. Our Templar friend Haytham and his cronies strike upon a plan to free the Mohawks, gain their trust, and thus find allies in their quest to locate a secret temple Haytham has been sent here to find,[6] which is apparently on Mohawk land somewhere. Most of the kidnapped Mohawks have the vague, slightly unformed look of random faces in the crowd, and their characters never rise above that level. The lone exception is a beautiful woman whose face and clothes show the careful design of someone who will be important to the narrative.

But beautiful though she may be, the woman’s mouth isn’t Native, her cheekbones are pronounced, but not quite right either, and the shape of her nose is all wrong. She’s essentially a white woman with darker skin and Native clothes. She even has freckles.

“Like Cameron Diaz with a tan,” says Tots.

When the woman, Kaniehtí:io, or Ziio for short, returns later with a speaking role, Worm jokes that she can’t be a real Indian because she doesn’t talk like one.

“She hasn’t said wick, or eeez, or ennit once,” Worm jokes, rattling off Rez-slang in her most exaggerated accent.[7] “She should be saying, ‘Gee, what ‘dem horses doin?’”

In fact, Ziio’s fluent, unaccented English make for a fairly funny stereotype-upending scene when she first speaks with Haytham. He says, “Me…Haytham…I come in…peace,” and she spits back, “Why… are…you…speaking…so…slowly?”

The talk of Ziio’s dark-white appearance was a more serious criticism than the rez-slang joke, but no one at the ambulance depot is making either of them too stridently. These observations are more in the realm of pointing out that the characters wear the same clothes in deep snow and summer sunshine, or that Kenway swims about as fast as Michael Phelps with a trawling motor up his ass—good fodder for joking around, but nothing worth worrying about too much. And really, there are no other criticisms of the game so far. It’s a testament to the efforts of the game’s designers, but also maybe a measure of just how low the bar has been set.

*****************************

“Natives in video games?” says sixteen-year old Bailey Clifford.

We’re in Bailey’s father’s house, a fairly new single-wide trailer bought through a federal program a few years back and set-up here in “Cliffordville,” the nickname given to the five Clifford houses spread out over a hundred and fifty acres or so on the edge of the White River and the Badlands, one of the prettiest spots you’ll find anywhere on the rez, or just plain anywhere. We’ve just been watching Bailey’s older sister, Soni, win the Miss Indian National Finals Rodeo Pageant live on the Internet from Las Vegas. Rodeoing runs deep in the Clifford family. Bailey’s dad Shane[8] is a former bull-riding and bucking-horse champ; Bailey’s bull-riding, rock starring, tattooing cousin Catlin isn’t competing this year, but he sang the Flag Song—the Lakota National Anthem—at the rodeo the night before, and an uncle is competing in the calf-roping division.

Above: Noah Watts

“I can’t really think of any,” Bailey says of Native characters in video games, “besides Red Dead Redemption. And then they’re pretty much just savages running around all crazy trying to shoot you, so you’ve got to kill them.”

A week later his cousin Catlin is back from Vegas, playing Assassin’s Creed with him, and I put the question to both of them.

“Gun is another one with Natives in it,” says Catlin. “But that’s about the same as Red Dead Redemption. They’re pretty much just savages. There are scenes where you’re just riding around and then there’s these screaming Indians chasing at you.”

“Yeah,” says Bailey, “they just run at you with no battle plan or anything, shooting all wild. They’re easy to kill.” Being portrayed as violent marauders is bad. But in the minds of experienced hunters and crack rifle shots like Catlin and Bailey, being portrayed as disorganized yahoos, lousy warriors and easy kills is far worse.

“There was Turok, a Nintendo-64 game that I really liked when I was a kid,” says Catlin. “Turok’s a dinosaur hunter who saves the world. It was full of stereotypes. He’s like one of these wise shaman-type guys who’s so in touch with nature and the spirits, and has all these special powers. But at least those are good stereotypes, you know? I dunno if it was offensive to other people that he had special powers and could shoot a bow—but I could relate to that. I wanted to have those powers and be a hero like that, and he was Indian and I was Indian. That’s how I saw it as a little kid.

“You can tell with this game that they actually tried to get some things right,” Catlin continues. “In Gun, they’re [Southwestern] Indians, but there’s a certain scene with a medicine man and he’s saying something about ghosts and he says ‘wanagis.’ That’s a Lakota word!”

“You can tell though,” Bailey says, “in this game at least, they went and used the right language, probably Native voice actors.”

Ubisoft did in fact use a number of Native voice actors, and I had the chance to talk to the primary one, Crow tribal member and actor Noah Watts, a few days later.

“When I tried out for the role, I thought it was going to be for a period piece, a movie,” says Watts. “They were billing it like a movie, to keep the plot of the game a secret. Now, I’ve played all the Assassin’s Creed games and I was reading the lines and I thought ‘This sounds like Assassin’s Creed!‘ But I thought there was no way they were going to make a Native Assassin. That would just be too cool. When I found out that it was, it was a real thrill and honor to get the role.”

Watts tends to land more roles playing contemporary Natives than buckskin-and-breechcloth historical types. One of his first gigs came with the 2002 film Skins, which was set and filmed here in Pine Ridge by probably the most successful Native director, Chris Eyre, and based on a novel by Adrian C. Louis, a Paiute author who used to teach at the local tribal college.[9] These Indie-an movies tend to have heavily Native casts and production teams. What made Assassin’s Creed different, he says, is that it was a non-Native creative team, but one that put as much priority on Native experiences and opinions as any other production he’d worked on.

“They hired consultants and experts, and every idea they had they tried to pass it by them first, to make sure it was as accurate and respectful as possible. The better directors, they try to respect our cultures, to understand that there are different indigenous cultures and that they’re all as valid as any other religion or way of living. They’ve been doing that for this game and I think it’s very respectful, and a good model for other companies, too. If they want to make stories about Natives that’s fantastic; they just need to include us in the process.”

And it’s not just the Mohawks themselves—their dress, their villages, their language—that the designers seem to have put a lot of effort into, but the surrounding historical context. Most of the action in the Haytham preamble takes place around the time of the French and Indian War, when the Mohawks and the rest of their Iroquis Confederacy teamed up with the British against the Algonquins and French. Thanks to The Last of the Mohicans it’s a story we know, and one in which we generally root for the British and the Iroquois. Only, teaming up with the Limeys was arguably the worst decision the the Iroquis and the Mohawks ever made.

France’s fur trading posts and military forts, dotted along the Great Lakes and the rivers connected to them, certainly led to clashes with Natives, but the French had more interest in trading with them than wiping them out. The English, on the other hand, saw the New World as an outlet for their “surplus population,” as Ebenezer Scrooge would later put it. They wanted not just a series of trading posts but a “New England” with it’s own cities and states and protectorates. To do this, the colonies needed land that could only be taken with smallpox blankets and bayonets.[10]

Surprisingly enough, this semi-esoteric historical fact is succinctly described by the game’s version of real-life British general Edward Braddock in a bit of martial, Walt Whitmanish philosophizing. The speech comes as Braddock prepares to battle not only the French, but his ostensible allies, Ziio’s Mohawks, a plot twist that is maybe light on historical fact, but contains a certain historical truth that runs throughout the game: alliances are fungible, motives are opaque, and everyone is more than happy to fuck over the Natives.

********************************************************

Back at the ambulance depot, Stephen’s telling a story about the first time his roommate met Tots. Stephen’s a white guy, but enjoys the kind of jokey, “there’s almost no such thing as offensive between us,” relationship with Worm and Tots that some of the funnier non-Natives who live or work on the rez get with Native friends and co-workers. Mostly he takes it, but he can dish it as well.

“My roommate’s a real asshole,” Stephen is saying, “he’s cool, but an asshole. So the first time he meets Tots he says, ‘Hey, is it true the police cars on the rez don’t have sirens? Just an Indian guy on the roof yelling, “Whoo! Whoo! Whoo! Whoo!?’”

People are laughing and the EMTs are telling war stories about car crashes, wild drunks, and diabetics so suspicious of hospitals they’ll let limbs go gangrenous and maggoty before they’ll call for an ambulance. There’s a lull in the hilarity when a call comes in about a guy threatening to hang himself right there in front of his family. The cops are on their way and will hopefully deal with the problem before things get that far, but Tots and Stephen are at the ready.

Above: Catlin Clifford

I don’t know enough about psychology to have a whole lot to say about suicides here on the rez (something like four times the national average) but the rate of unplanned, impetuous suicides—which this call sounds like it might be—seems particularly high. One night last summer, a buddy of mine’s former boss got blanco, got in a fight with his girl, and then a footchase with the cops. He made it inside his house and found a gun before they could grab him and boom! it was all over.

“If that gun hadn’t been loaded, or if the cops had gotten him and dragged him in to the drunk tank for the night,” said another friend of the deceased, “he’da woke up hanging over and laughed about the whole thing, no big deal. He wasn’t a depressive, suicidal sort of guy. Just wild.”

Some local groups have started to address the suicide problem, but even that can be a mixed blessing. There are few people arund here with the proper training to really deal with psychological trauma, and there’s a case to be made that bringing more attention to suicide might actually make it more oddly appealing, especially to young people. If you’re a poor-ass kid who no one ever gave a shit about, and then you see some other poor-ass kid no one ever gave a shit about being eulogized and mourned by hundreds, her former enemies and no-account parents turned guilt-ridden and miserable…? Not many will make that decision. But far too many do.

As we wait to hear if Tots and Stephen need to respond to the suicide threat, I start to remember my original concern in trying to zip through the first parts of the game: the generally high level of excitement on the rez, and how it translates into ambulance runs. This is my first time in the ambulance depot, but I’ve been on ride-alongs with cops on the rez before and the workload can be frightening. On one ride-along, I went from Whiteclay, where a drunk had just slugged a Nebraska state cop, to a domestic dispute over who owned a horse after a messy breakup, to staking out the family house of a guy on the lam who’d been seen around town[11], to a call about a car full of drunk guys waiting outside another guy’s house and loudly announcing to the neighborhood that they were going to kick his ass, to a highspeed chase that we cut short when the driver took his old, brown, rez-bomb Buick straight through one of the three stoplights in town, barely threading the needle through the busy intersection, to helping a cracked-up car full of elderly people that said Buick ran off the road (and was one last foot of guardrail from pitching down a lethally steep embankment) even though we’d stopped chasing him two miles before, to watching impotently as my police officer tour guide used a tazer, pepper spray, billy club, car door, and some well-timed tackles to subdue the three guys in the car when we finally found their wreck further up the road. All of this, if you don’t count the time we spent in the jail booking a wino for public drunkenness, was in the first hour-and-a-half of the shift. The sun had barely set.

“Heeeyyyyy, Uncle,” I heard the thirty-ish driver of the car say to his older compatriot in the back of the cruiser, after he’d cried and coughed away enough of the pepper spray to talk. “I think I wrecked your car, man.”

“Shiiiitt,” said the older man, who turned out to be the ringleader of this particular circus, something to do with getting revenge on some guy who’d snagged up his woman. “You didn’ wreck nothing. If I’da been driving you’da seena wreck!” After some quick blood tests at the hospital they were both in jail, bloody, battered and telling jokes with the same cops they’d tried to fight an hour earlier.

My dad’s a retired cop (albeit in one of the safest cities in America) and I’ve covered cops and firefighters as a reporter in New York City and the Boston area, but I’ve never seen first responders work like they do in Pine Ridge. Complicating matters is the reservation’s size. Physcially, it’s larger than the state of Connecticut, but in terms of population it’s more like a large town or extremely small city. What that means is that you’re almost invariably having to arrest or resuscitate a cousin, a high school nemesis, the sister of an ex-girlfriend, the son of a tribal power-broker, etc.

I have more than a few friends who’ve benefitted from this fact, getting pulled drunk out of a ditch-driven car by a friendly face who drove them home to sleep it off. I’ve also met my share of cops who’ve dealt with the flip-side. One possibly (but probably not) apocryphal story has police responding to a wild party at a powerful tribal council member’s house, only to find the beer flowing like wine, and a table piled high with coke, pills and weed. The place went silent at their arrival, and the host pushed his way through the crowd and past the cops to take his appointed seat in front of the drug bazaar. He told them who he was and just what kind of trouble they’d be in if they tried to arrest him or any of his guests. Then he leaned down, took a rip-roaring snootful of blow and turned back to the cops, party-powder granules still clinging to his nose hairs, and said, “So. What are you gonna do about it?” The cops just left.

The busiest nights, Worm and Tots are saying, are on the first of the month,[12] when welfare and social security checks come out and again around the tenth, when Electronic Benefit Transfers, the debit-card successor to Food Stamps, are made. For most people, EBT day just means a week or two of decent eating, the wildest thing associated with it being the Sharps Corner Common Cents convenience store, which normally shuts at nine, re-opening at midnight after a thorough restocking to deplete EBT cards well into the wee hours. But as with any place, there’s no shortage of people around here desperate enough to trade EBT funds that are supposed to be feeding their kids for a few quarters on the dollar to feed their respective addictions. This means plenty of partying, plentying of reckless driving, and plenty of 911 calls.

Above and at top: Bailey Clifford

Word eventually comes over the dispatch intercom that the cops talked the guy down from committing suicide. Lord knows what happened to him from there.

By this point in the game, Haytham and Ziio have teamed up to save Ziio’s village from the aforementioned General Braddock. Shortly after Braddock delivers his Lebensraum-soliloquoy, Haytham and Zio take him out, and then Ziio leads Haytham on a quest to open the ancient temple he’s been after. They’re unsuccessful, but make due with a romantic evening under the stars. (“This is where she got her nickname, Macajawea,” someone says to begrudging laughter.) Fast forward a decade, and Ziio is a single mom raising her son in her small Mohawk village, his father too focused on the Templars and their epic questing to care much about either of them

We’ve finally entered the the advertised part of the game, the Hero With a Thousand Faces-esque rise of future-Assassin Ratonhnhaké:ton, aka Connor. At the ambulance depot, the reactions to the Connor assassinsroman is solidly positive. The Mohawk language is the biggest hit—noone knows how to speak it, or how well it’s being spoken here, but language revitalization is about the most uncontroversial, unadulterated good that can be done on a reservation, so everyone’s in favor. The village looks accurately done (longhouses, not típis) and most of Connor’s fellow tribesmen have as much flesh and bone to them as any one-off video game characters can be expected to have.

There are hunting scenes, where you have to use bait and snares (“Turn up my snare!” another EMT, Isnalawica, says in his best Eminem). The bow-and-arrow hunting goes over even better, no surprise given the crowd. Worm is a middle school archery coach, and took second place last year at the American Indian Higher Education Consortium (the tribal college version of the NCAA) archery meet. Tots’ dad is a skilled bowhunter, and while Isnalawica is more of a gunpowder guy, he’s been thinking about taking up the bow. There were some nitpicks, including the fact that supposed deer tracks in fact look like elk tracks, and the structural impossibility of the bow Connor uses. Still, the bow looks pretty wick, and it’s hard to expect a bunch of agorophobic programmers to know too much about the subtleties of stalking even-toed ungulates.

Here the game deals a bit in the “good stereotypes” that Catlin spoke of earlier. If you don’t harvest the meat and hide from an animal that Connor kills, the game tells you he wouldn’t have let it go to waste like that. Someone jokes that Connor’s village must have a full-time house band or an Ipod, playing traditional drum songs in the background, and Connor of course goes on a vision quest.

Good stereotypes are maybe just the flipside of bad ones, but just as you’ll be hard pressed to find many Irishmen who’ll complain about being stereotyped as charming, tragic, Guinness-quaffing wordsmiths, you won’t find a lot of Natives who are too upset about being seen as skilled hunters who revere nature and abhor waste.[13]

At any rate, while Assassin’s Creed III does deal in some stereotypes—though mostly just good ones—it also deftly undercuts both historical over-simplifications and personal ones. As Connor moves forward through history, exhibiting an almost Forrest Gump-like ability to play a pivotal role in nearly every major historical event in the Revolutionary era, it becomes less clear what exactly is driving him. Concern for his village and Mohawk people? Blind rage and vengeance for the murder of his mother? A yearning for acceptance from that absentee, enemy of a father?

Also increasingly unclear is what exactly Connor should be doing to protect his village, the ostensible goal that started him on his quest in the first place. The Revoluitonary rallying cry of freedom is an initially compelling one for Connor, but as he soon finds out, slaves, Natives and the poor need not apply. One minute he’s saving George Washington’s life, and the next Washington is plotting to destroy his village. Should Connor be supporting anyone in this white people’s war? Should he have just stayed home?

In the game, the complications come to a climax when Connor’s all but forced, in a cut scene, to kill a childhood friend from his village, who’s been conned by a Templar into thinking Connor is a murderous traitor to his own people. But the scene begs the question: once Connor pulls a General Westmoreland, destroying a fellow member of his village to save it, has he not in some way become that murderous traitor?

There are some truths in these conflicting ideas, and on some level they relate to contemporary reservation life. What rez-ident hasn’t faced the conflict of what it means to be Native, but also an American? Between national, mainstream values and measures of success, and local, tribal ones? Or the question that Connor was forced to deal with, of staying home or venturing out, of protecting the tribe from without or strengthening it from within? But sitting at the ambulance depot or in Cliffordville, these issues do feel a bit abstract and Ivory Tower.

Since the 1960s, few political wires have been more live than identity politics and mass media depictions of historically-screwed minority groups. Pine Ridge has been no stranger to the phenomenon, thanks to the 1970s AIM-era and the general upsurge in cultural pride and preservation that has followed. “For a long time, we were supposed to be ashamed of who we were,” an old-timer once told me. “They’d cut off your braids when you went to boarding school, and wash out your mouth with soap for speaking Lakota. Families changed their names to things like ‘Black.’ It’s different now. Families call themselves Black Feather again.”

It’s a testament, perhaps, to how much has been accomplished on these fronts internally, on the reservation, that most of the people I spoke and played Assassin’s Creed with didn’t seem all that concerned with how the outside world percieves or depicts them. Most people have some form of access to that outside world—satellite tv, the Internet, occasional travel—but few put much creedence in the kinds of debates that roil college campuses or cable news studios.

“It’s like your own little world here,” says Worm. “I was in Ohio a couple weeks ago and they were all talking politics all the time, getting fired up about these things because one was Republican, one was Democrat. It’s not that I didn’t care about the election, but I don’t understand why people let things like that upset them so much. It’s almost,” she says, teasing me, “like a weird white people thing.”

I don’t disagree, and have some half-formed thoughts about what it says about our culture that we use abstract political beliefs to define “who we are” to the outside world, or that we seek so many of the little morality tales that help us make sense of life from professional sports and celebrity gossip, instead of the actual lives of real people we know and can commiserate with.

Pine Ridge, on the other hand, has a fairly self-contained culture, one where media exists but isn’t prioritized, and where people usually have bigger things to worry about than getting all worked up about some stupid fashion designer putting headdresses on models. Not that it doesn’t piss people off, mind you. Who’d want their culture treated as some silly dress-up game, particularly when that culture has survived hundreds of years of explicit ethnic cleansing by the media and political power structure? But for the most part, stories like that are met with a little laugh and a knowing look that seems to say “Ohhhh, white people. What did you expect?”

“Over the years the people that wanted to be a part of Native society or whatever—like the classic white guy who claims he’s Cherokee, or German tourists that try and sneak into Sundances—they give it a bad name, and so some people around here just don’t like anything about Natives that you see [in the media],” says Catlin. “But usually people are pretty cool about it.”

That’s particularly true if the movie, or television show, or video game is especially badass and entertaining. Sure, Taylor Lautner is a white guy playing a one-dimensional Native in Twilight. But that didn’t stop the local Numpa Theater from showing the movie to packed houses last week, or the mostly female audience from breaking into ecstatic “Li-li-li-li’s,” every time he took his shirt off. Johnny Depp looks awfully silly in stills from his upcoming Tonto and Lone Ranger movie, and most people will roll their eyes at the Elizabeth Warren-levels of Cherokee blood he claims to have. But if Johnny Depp is as entertaining as he usually is, and the movie’s big special effects budget is put to decent use, Numpa Theater will probably have another hit on its hands.

I make roughly that point to the assembled EMTs and get some vague assent, but mostly just tired shoulder shrugs. It’s closing in on two o’clock on Sunday morning, which means they’re barely halfway through a 48-hour shift. Things might perk up in a couple of hours, or they might stay calm through the night. Either way, it’s time for the EMTs to get some shut-eye. The game was pretty good, people are saying, and all this stuff about how Natives are depicted is kinda interesting. But Tots and Worm and Stephen and Isnalawica are taking classes, making ends meet, planning weddings and dealing with breakups, just like any other group of twentysomethings. They need to take their rest where they can get it.

[1] I’m forever grateful to Worm for this, as it’s been an exceedingly long day. I spent the morning and afternoon out bow-hunting, only to have a pair of gun hunters Elmer Fudd their way in to a ridgeline and scare off all the deer just as they were coming within bow range, then start winging futile shots at the retreating herd close enough that I heard the hiss of the bullet cutting through the air before the ringing “Thud!” of the gunpowder concussion. Then I arrived home to see a few members of the local skunk population duck into a well-hidden hole they’d dug under the crawl space beneath my trailer house. They pulled the same move last winter and it took me, a team of local kids on break from college and enough small arms firepower to make the cast of The Walking Dead jealous to dislodge them. As a general rule, I don’t kill anything I’m not planning on eating, but just as there are no atheists in foxholes, there are no animal rights advocates living above America’s stinkiest, rabies-ridden scavengers.

Wick is short for wicked, and is used fairly interchangeably with vish—for vicious—as something of a positive modifier. People in Ridge use it in more or less the same way that Bostonians use wicked, for reasons no one quite seems to understand. Do-gooder Catholic volunters maybe, bearing catchy colloquiallisms? Just as the intensifier “pissah” can be added to “wicked” in Masshole-ese to make it something resembling superlative modifier (“Paaawwwlll Peeeeyce threw a wicked pissah no-look pass to Rondo,”) pure can be added to wick or vish to really up the ante on a sentence. (“Eeeeeez, that pass from Pierce was pure wick, ennit?” “No way, Pierce is ched.”)

Intensifiers like Eeeeyyyy and pure actually fill the same linguistic role in rez-English that the Lakota word áta did in the old days. “It’s always hard to say how much rez-slang is derived or influenced by the original Lakota,” says Peter Hill, a fluent Lakota speaker and teacher, and perhaps the only guy on the rez who’s skinnier and whiter than I am. “But with áta and Eeeeezzzz it’s pretty clear.” There’s a case to be made that the local tendency to shorten words (wick, vish) also has a forerunner in Lakota “fast speech,” an informal speaking style that shortens and combines Lakota words. But shortening words is very much a Pine Ridge phenomenon, not done as commonly on other Lakota reservations.

My little sister works at the Southie Boys and Girls Club, so I had her ask as many kids as possible a simple question: would you rather be from somewhere people know about, but for bad reasons, or a place that no one knows or cares about? The results were pretty interesting—nearly all of the boys said they’d rather be from a big, bad, famous place, while the girls said the opposite. This was maybe just the small sample size or maybe the fact that anyone in their right mind would rather be associated with Ben Affleck than, say, Jill Quigg, but its certainly interesting. The best recent take I’ve read on the complexities of growing up in a changing Southie, check out Boston Globe reporter Billy Baker’s article on the subject from this summer.

The most fascinating thing my sister’s informal research turned up, though, was how many of her kids were actually playing Assassin’s Creed III. Some were already fans of the franchise, some found out that it was mostly set in Boston and wanted to check it out, and pretty much all of them love the game.

“I bought it based on the commercials,” thirteen-year old Robert Lee told me over the phone. “I didn’t know the backstory or anything about the characters. I just figured it would be cool to play a game in Boston. And the game is great! You go through pretty much every historical event that happened, the Boston Massacre, the Tea Party, Lexington and Concord, everything. All the little maps had great detail of Boston, they even had the Back Bay and Fenway still all covered in water. And I liked having the Native Americans in there. You got to hear their language, and kinda get both sides of the story.”

The Native aspect had a special appeal to brothers Mark and Matt Walsh, too. They’ve got a little bit of Native blood on their mother’s side of the family. It’s not something they know much about, but said it was cool to see that shown in a game.

Photography of Bailey and Catlin Clifford by Angel White Eyes, a student at Oglala Lakota College.