As with most indie events in NYC, attending the showing of “If You Can Get to Buffalo” had me asking my usual first question to anyone within earshot: “Am I in the right place?”

Even as I was shepherded into a hidden theater deep in the unmarked Episcopalian church in the East Village, the confusion continued. A sound check on the center stage was being done be a disheveled man with a fabulous porn ‘stache in grungy clothing. The shadowed figure sampled and layered music from the early 90s in an eerily chaotic fashion, and it became clear as the lights went down and the players entered the stage that this was a character who was laying down the unsettling tone of the piece and introducing us to the show’s antagonist.

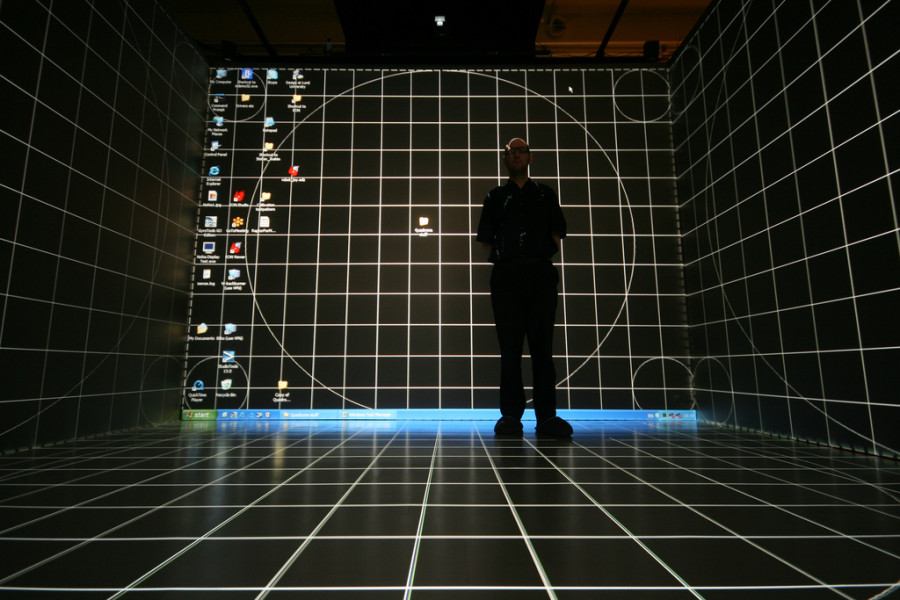

Lit up suddenly by individual spotlights, the actors appeared and were typing away at their keyboards, sitting in front of two long tables facing towards the audience. A projector screen on the wall straight ahead of the audience displayed scrolling text, describing the cyber house that these chat room participants had gathered in: LambdaMOO.

The year is 1993, a time when the Internet as we know it was just beginning to form into what it is today, a holodeck powered by imagination, a virtual playground where you can be anyone and do anything you’d like—chat room rules permitting. LambdaMOO was a take on the MUD (Multi-User Dungeon), but in this instance the combat RPG elements were replaced with more whimsical actions: dancing on the ceiling and pretending to sing Fred Astaire songs in a makeshift cabaret living room.

While the characters speak with one another, their voices overlap as they would in a chat room. To further punctuate the cyber feeling, the actors move often robotically through the stage, synchronised dancing sessions breaking out between scenes; the projector screen matches monologues from characters who talk of everything from the mundane to the absurd. There is a hint, occasionally, of the perverted.

Slowly, it becomes clear: there is a wolf among them, someone whose idea of paradise comes at the expense of everyone else.

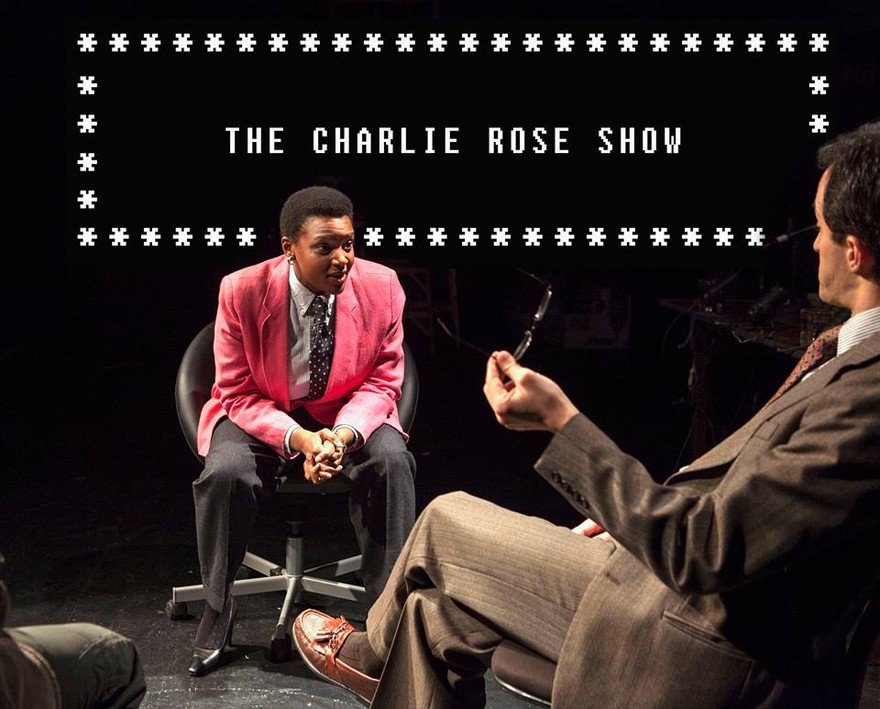

Between fantastical MOO chat moments, the lights focus on the front center of the stage while three characters take a seat in the physical world in a triangle pattern. These moments spotlight an interview between a clueless and disbelieving news anchor (who considers the Internet to be a passing fad), one of the LambdaMOO chat room participants, and a New Yorker reporter who pretended to be a woman in a chat room with the assistance of his wife.

Between fantastical MOO chat moments, the lights focus on the front center of the stage while three characters take a seat in the physical world in a triangle pattern. These moments spotlight an interview between a clueless and disbelieving news anchor (who considers the Internet to be a passing fad), one of the LambdaMOO chat room participants, and a New Yorker reporter who pretended to be a woman in a chat room with the assistance of his wife.

Our LambdaMOO participant/narrator all but sidles up next to the audience as he passionately defends the legitimacy and realness of the harassment and subsequent cyber-rape that eventually takes place in the chat room, despite the protests from the news anchor and the New Yorker reporter that this situation was make-believe and that no real harm was done.

And though the rape may read in an absurd fashion on the chat screen alone, with its voodoo doll domination and ultra-violent kitchen object penetration, the audience sees true traumatic horror in the faces of those sitting behind the keyboards. You feel chills when one of the wide-eyed participants flips the table in a passionate furor. You clamp your hand over your mouth as she sits with her back against the table in traumatic silence, taking stock of how quickly this playful paradise became hell.

This is all based on a Village Voice piece by Julian Dibbell, a prophetic 1993 piece that explores “a rape in cyberspace” and makes you question whether there is a distinction to be made between the physical and virtual worlds in terms of personal responsibility and consequence. In other words: is harassment any less harmful (or somehow more acceptable) just because it’s done online rather than in person?

My idealistic self says: NO, absolutely not. Let’s burn at the stake every smug troll who makes cavalier death threats while anonymous and puts the burden on law officials to petition ISPs to reveal IP addresses and social sites to reveal real names of—okay, dammit, my practical side just kicked in. We obviously don’t have the manpower (nor the laws) to regulate the sheer volume of harassment that takes place on the everyday Internet.

The once-shocking “Rape in Cyberspace” from is now every instant spent reading Twitter or YouTube comments. It’s clear that there is no longer an expectation that being on the Internet will allow you to escape from the physical world’s harassers. Your escapist fantasy may involve being a dragon-riding Warrior Priestess with an affinity for lemur charming, but somewhere, within arm’s reach, someone is typing in the command to tell their avatar to pelvic thrust your head because you refused to remove your clothes. Or simply because you were the closest living (or dead) person nearby.

But that’s a small manifestation of a real issue: take, for instance, YouTube videogame personality totalbiscuit and his recent announcement that his health has become so alarmingly bad due to constant harassment that he’s actively avoiding reading any comments on his content. Consider that Anita Sarkeesian of Feminist Frequency has had to have YouTube comments disabled since nearly the beginning of her series due to virulent harassment and that she frequently reports violence, rape, and death threats on Twitter, which go unpunished.

Another popular YouTuber, boogie2988, gets to the heart of the issue and has covered this topic fairly regularly in the past: “The job is technically easier, but there is a price, and the price is hateful emails. The price is hateful tweets. The price is having people harass you in public and online. It’s to have people try to fuck with you, to dox you, to share those dox, to try and hack into your account, to fucking deliver pizzas to your house, to try and swat your home, put nasty, disgusting things in your PO box, to harass you, to destroy you, to wreck you, to tear you apart.”

The Rooster Teeth crew of the popular Red vs Blue series based in the Halo universe have a love/hate relationship with their audience as well, frequently airing their grievances on their podcast. CEO Burnie Burns has lamented that he can’t, in some magical manner, prevent terrible people from consuming his company’s content so that he can be free of trolls.

Perhaps most disturbing about the present state of the Internet vs. its 1993 counterpart is that anonymity isn’t even required on the part of the harassers. Why bother using anonymity when there are little or no serious policies or enforcement measures taken on major networks? A great many services now have some degree of connectivity with a “real name” service, but that’s not stemming the thousands of paper cuts that are the cause of constant anxiety, and the feeling of utter dread and violation is no less real. For additional reading if you’re unfamiliar with just how prevalent this feeling is: Why Women Aren’t Welcome on the Internet.

At its heart, “If You Can Get to Buffalo” is absurd. Yes, the goofy videogame-inspired settings and situations and theatrical interactions are absurd. Yes, the presumption from outsiders that violations are acceptable as long as they’re done remotely is absurd.

But the thread that connects the two worlds is ordinary humans just doing their damndest to be happy; ultimately, the smug news anchor secretly turns to the Internet with reluctant but palpable excitement at the end of the play, typing away in a chatroom in the hopes of making an exciting new connection. “If you can get to Buffalo…” she says as she types, hoping to connect offline with her newfound Internet compatriats, no longer deriding this cyber-world. In some ways, the play proves that we don’t need VR headsets or increasingly haptic controllers: virtual places can already be startlingly real.

Header image via Zebra Pares

Charlie Rose image by Brendan Bannon

“If You Can Get to Buffalo” was written by Trish Harnetiaux and directed by Eric Nightengale. More info on it can be found here.