The much-anticipated new iterations of Nintendo’s Mario and Zelda franchise have just been released—and, like most games in these series, to critical acclaim. (We loved Mario; less so, Zelda.) Both have been called the best game in their respective series: Super Mario 3D Land adds the four playable characters of Super Mario Bros. 2 to the Super Mario 3D Land template, and A Link Between Worlds brings the magic of 1992’s Link to the Past to a new generation. Both are looked to as reasons for their respective systems to exist, and this may very well be the case. But it might also be because they remind people of games they’ve already played—some over 20 years ago.

I’d be far from the first person to accuse Nintendo of preying on consumers’ nostalgia in order to get sales. The company is criticized for their long-running series, and dissenters regularly say that the company keeps on releasing the same product over and over with updated visuals. Both parties, those pro- and anti-Nintendo, say the designers appeal to their audiences’ nostalgia. But what does that term even mean?

It gets thrown around a lot these days, specifically in conversations about videogames. To be clinical, it refers to sentimentality for the past—for memories. However, this can be troubling; according to research done by Northwestern Medicine and published in the Journal of Neuroscience, “A memory is not simply an image produced by time traveling back to the original event—it can be an image that is somewhat distorted because of the prior times you remembered it.” In other words, when you remember something, you’re only remembering the last time you remembered it; and it is therefore affected by your mood at the point of remembering it. It means you remember things, in part, how you want to remember them. Or, perhaps, how others want you to remember them.

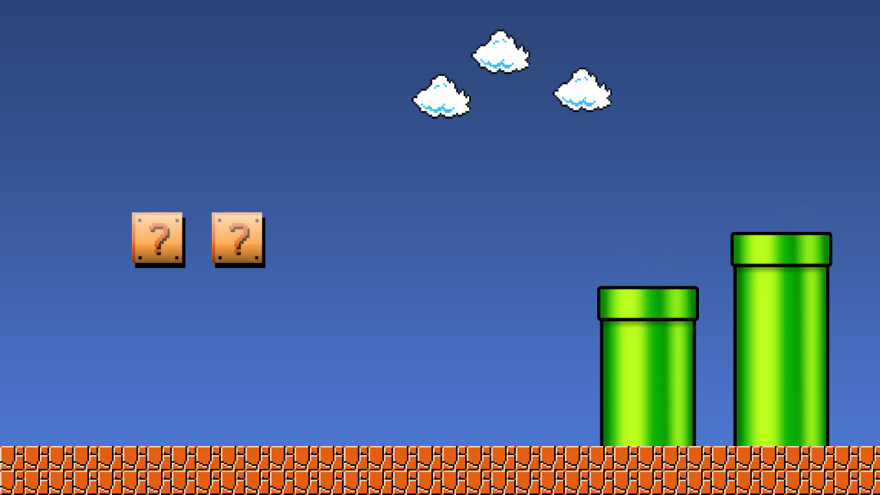

Some of the most powerful tools people interested in manipulating nostalgia have are images and symbols. Sociologist H. A. Overstreet spoke about the power of these tools in a lecture series called Influencing Human Behavior. He realized that people more readily understand things when explained using the “language of pictures,” and how “selective images” can be used to convey ideas and instruct a viewer on how to interpret an image shown to them. Now think about all those repeating elements in Mario and Zelda games: the 1-up mushroom, the star, the cracked wall in a dungeon, the eye switch, and how you were introduced to each one. Anyone who’s played even one game in the series knows exactly what to do when presented with these symbols: collect the mushrooms and stars, bomb the crack, shoot the eye with an arrow. Through repeating these elements in every game, Nintendo creates a visual language that players can very quickly understand and read. They’ve created an actual map-like legend for Zelda and Mario, a handy dictionary of images that teaches one to play without tutorials.

However, games are more than just a collection of symbols to identify; any franchise and every medium has its own visual short-hands and recurring tropes. Games, we know, are different because they’re interactive. Games aren’t just a bunch of one-way signs along a straight road; they’re full of many different signs guiding players along complex systems. And these complex systems are expected to work in the way that all of these signs tell us they should: making a self-contained environment that should make sense to anyone who jumps in. Media philosopher Walter Lippmann wrote about these systems as “pseudo-environments.” He believed that for the world to be understood it had to be broken down into smaller, pre-constructed and easily digestible pieces that tell whoever enters them everything they’d have to know about them. These pseudo-environments determine a person’s thoughts, feelings, and actions, and they inform people on how to behave given the world they inhabit. Games don’t just give us a world to explore, but tell us (some more subtly than others) how to explore it.

Nintendo is a master at creating these environments and teaching people how to explore them through constant iterations and reuse of assets. Anyone who has played any one of the games in the franchise already knows how to play every other game in the franchise, and this familiarity plays on the player’s nostalgia for the last time they played the game. If they enjoyed it the last time, chances are they will enjoy it again the next time, and the time after that. They create their own visual language that tells you that how you have fun in this new game is by doing the things you already had fun doing in the last game. In Nintendo games you have fun by having fun. Think about how happy you might have been to see Whomp Fortress in Super Mario Galaxy 2. I’d guess this probably has less to do with the actual level itself, and more to do with knowing you’ll have fun playing through it again because you had fun playing through it 16 years ago, as a child. That feeling—of thinking you’d be happy doing something that made you happy in the past—that’s nostalgia.

This is also the reason Nintendo skews younger than most other studios. While other publishers are aiming towards older, more monied demographics, Nintendo still focuses on selling to children. Because they’re one of the few videogame companies actually looking for children’s attention, children give it to them, and this allows Nintendo to start teaching them their visual language from an early age. And that, in turn, gives those children memories of Nintendo to refer back to when they’re older. Older people then buy Nintendo because it reminds them of their childhood. Using familiar symbols and systems Nintendo creates through-lines from every new game right back to your childhood. Nintendo becomes nostalgic in a very true sense, then. When an older person plays a Nintendo game they aren’t just playing that game, and they aren’t just playing every other game they’ve ever had a good time playing. They are reliving their childhood: going back to familiar systems and symbols that have always made sense to them, and will always make sense to them. And they will always be fun, because that’s how they’re designed to be remembered.

Second image via Julia P