We are now in Dante Alighieri’s 750th year. Though we do not know the exact date of his birth, we know that Dante was a Gemini thanks to an oblique admission in Paradiso (Canto 22) which narrows the options to between May 15 to June 15; a story reported by the Italian poet Boccaccio indicates that he was born in the month of May, further narrowing our options. Which means that literary and historical websites and magazines have long since churned over that particular field, discussing the effect Dante’s epic poem about Heaven, Hell, and everything in between has had on history and art; it is only fitting that a discussion of Dante and videogaming comes tardy, given the medium’s relatively late entry to the aesthetic field.

Leaving aside the inescapable cultural ties between Dante and the demonic (for example, the Devil May Cry series has a protagonist named Dante, though this is more of a referential connection than a substantial one), the great moment where videogames collided with the author of La Vita Nova came in 2010 with the release of Dante’s Inferno. The game was initially controversial due to its profoundly tactless marketing strategy: there were paid protestors acting like the Westboro Baptist Church’s book club, websites that let you upload your friends’ pictures and condemn them to graphically bizarre punishments, and an annoying box that you had to smash to silence whereupon it would accuse you of being wrathful. And then there was the minor tiff over the knife-armed souls of unbaptized infants. As far as nuanced references to the Inferno go, EA’s marketing division made Devil May Cry look like Boccaccio.

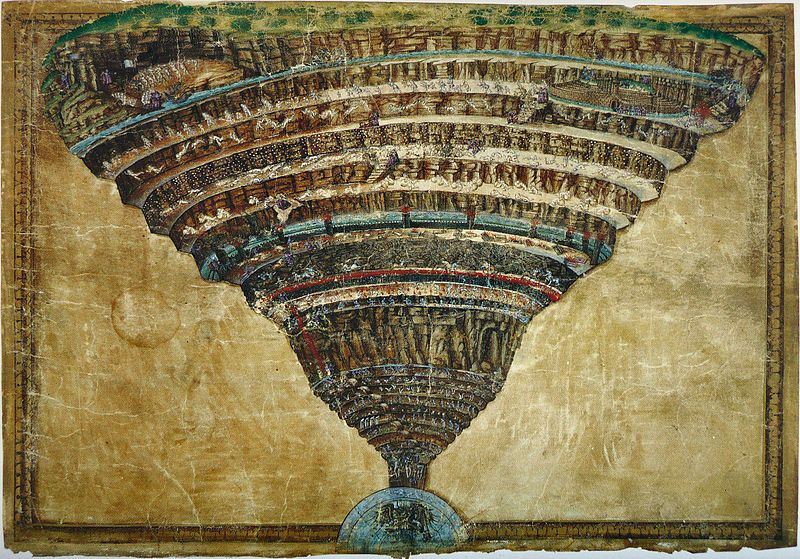

Sandro Botticelli’s Chart of Hell (1480-90), via Wikimedia Commons

But when the game was finally released, it was welcomed by lukewarm reviews. It was a mediocre clone of the then-popular God of War series, an easily caricatured example of ludicrous hypermasculinity, and took serious liberties with the theology behind the original text. Those more familiar with the original poem talked of how well it managed to illustrate the geography of Hell in some parts (for example, the seventh circle), or examined how it worked the original’s thematic concerns into level design. The fourth circle’s use of gears and moving platforms, for example, deftly invokes the medieval conceit of the Wheel of Fortune and the Sisyphean punishment of spendthrifts and misers. At the same time, a Dantista from Columbia University excoriated the videogame for misrepresenting the entire romantic momentum of the Comedy by turning Dante into Mario, who plumbs the underworld to rescue his princess—in essence, defacing Dante’s religious adoration of an image of divine grace by portraying it as cliché eroticism. That Dante’s Inferno employs tasteless nakedness to indicate her beatific status makes it worse. This fallen representation was, of course, but one of the many marks made against the game after its release.

But nowhere was there a discussion of Hell’s dramatis personae. The beauty of the whole Comedy lies not merely in its careful design, the allegorical theology, or in its language, but in the people that populate heaven, hell, and purgatory. Contemporary or classical, the circles, spheres, and cornices of the poem are filled with lively presentations that bring home the character of the poem—figures that are essentially absent from the videogame. Where is Ulysses, who gives one of the most impassioned and beautiful speeches in the Inferno:

“Brothers,” I said, “who through a hundred thousand

Dangers at last have reached the occident;

To this short vigil which is all there is

Remaining to our senses, do not deny

Experience, following the course of the sun,

Of that world which has no inhabitants.

Consider then the race from which you have sprung:

You were not made to live like animals.

But to pursue virtue and know the world.”

Where is Guido da Montefeltro, the soldier turned priest condemned to Hell for breaking his vows by offering military advice to Pope Boniface after the latter assured him that he would be pardoned for doing so:

“Francis afterwards, when I was dead,

Came for me, but one of the black cherubim

Said to him: “Do not take him: do not wrong me.

He must come down and be among my servants,

Because he gave fraudulent advice,

Since when I have waited to seize him by his hair;

For absolution is for the repentant;

You cannot repent and will at the same time,

The contradiction is not allowable.”

To be fair, these are characters from the eighth circle, which was truncated into a series of combat challenges in Dante’s Inferno. Instead, where is the Paolo and Francesca from the poem, the two adulterers bound together throughout eternity, who talk of how they were seduced not by each other but by the story of Lancelot and Guinivere? In the game they are treated as collectibles, depicted as exchangeable naked wretches rooted to the ground, and lose all individuality by merely begging for mercy— “have pity on our perverse will” —or protestations of sincere love—“it was not a passing romance; it was our destiny!”

In his Dante: Poet of the Secular World, Erich Auerbach argues that Dante’s Comedy is the first work in the western tradition that portrays men and women in fiction as we are familiar with them in our day-to-day lives. To do this, he outlines Dante’s reliance on the medieval idea of the Habitus: “every action, every exertion of the will toward its goal leaves behind a trace, and the modification of the soul through its actions is the habitus.” We draw the word habit from habitus, but we use it flippantly (“smoking is a bad habit”) without the seriousness of its Latin denotation: a true habit is a reflection of the internal, something you do without thinking, an almost reflex-like expression of your character. Aristotle writes about how excellence is a habit, meaning that this high achievement of skill is something that comes preternaturally to a person. But this is not a deterministic model: habits are formed, through action or inaction. A habitus is, ultimately, the culmination of the choices you have made, the essence of who you are.

This is, according to Auerbach, the true genius of Dante: “Thus Dante undertook to portray the human beings who appear in the Comedy in the time and place of their perfect actuality or in modern times in the time and place of their ultimate self-realization, where their essence is fulfilled and made manifest forever.” Dante takes the habitus of his characters, and presents them in their fulfillment: Paolo and Francesca are caught up in the winds of lust in Hell just as they were in life. Their punishment is not ironic retribution, but the logical continuation of their selves after death. It is this conception of character—an essential attribute, reaching out into eternity—that leads Auerbach to call Dante the first poet of the secular world, as his conception of character prefigures that which modern art (with its novels, short stories, plays, movies, and so on) would adopt.

This failure of character is the underlying failure of Dante’s Inferno’s appropriation of the Comedy. Hell is not merely a visual environment: it is filled with people absent from the game as a whole, save for when they are placed as mere mechanical objects to be taken advantage of for experience points. In essence, Dante’s Inferno falls into the great trap of videogames: it transforms people into mere game mechanics that the player must abuse, not characters to be engaged with. In this dynamic, the protagonist then becomes another mechanism for the player’s entertainment. Though Satan tells the digital Dante that, “this is your hell,” the original Dante’s Inferno is very much a microcosm of the world itself: he encounters those familiar to him in off-the-cuff moments, just as we might walk down the street and meet the father of a friend or a former teacher. This Dante certainly has a privileged status in the poem, but it reflects the privilege of grace dispensed by God through Beatrice; the videogame’s Dante is just a solipsistic protagonist.

To be fair, Dante’s Inferno tries to present a narrative reckoning of digital Dante’s past misdeeds: this new Hell is designed to be a reflection on his own failures of Lust, Greed, and Violence; every other boss battle is another person from his past. Passing through each circle and defeating each foe is then meant as a mechanical representation of catharsis. But this is the same model the game uses for the various sinners scattered about the circles. Put another way, the central failure of Dante’s Inferno’s adaptation of its original is its transformation of a pilgrim into a warrior. As a pilgrim, Dante travels towards a final destination, engaging with people on the way, discovering new lands, all of which are incorporated into the final revelation that comes with the completion of the journey. As a warrior, other souls are only impediments to be overcome or tools to be leveraged.

But Hell is other people, not mirrors. The videogame version is made for you, the player, to win; the poem presents the whole of the (Western) world through its various peoples and has no such egotism, for Dante’s Comedy is ultimately about love. Not the cliché romance between Beatrice and Dante, but the disinterested “love that moves the sun and the other stars”—stars absent from the ending of Dante’s Inferno, which sees our naked warrior standing before Mount Purgatory in open daylight.