The Cat and the Coup is a valiant attempt at what may be an impossible form: the documentary game. That’s how Peter Brinson and Kurosh ValaNejad bill their surreal interactive hagiography of Dr. Mohammed Mossadegh, the democratically elected Iranian Prime Minister who first privatized the country’s oil fields, and whom American and British secret services consequently conspired to depose in 1953. The freeware game first made waves at IndieCade last year, and now, it’s widely available on Steam. In an age of shallow historical memory, it performs a service simply by reminding us of a significant international controversy, and will surely give Stephen Kinzer’s All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror a salutary bump on Amazon. It’s also a charming and poignant—if sharply curtailed—experience. However, to call it a “documentary game” distorts both terms.

Indie documentary games have been made about everything from JFK’s assassination to the Branch Davidian siege, and the idea that games can teach us about history has infiltrated the mainstream in the guise of war simulations. Though the educational value of the documentary game has been hotly contested, the coinage endures: it makes a brave sound, assuaging our secret anxieties that gaming is pure escapism. But the documentary form itself presents an immediate challenge to interactive media, which are always about the user’s ability to guide the course of events. How should we meaningfully do that in a story where every detail and outcome is preordained?

The Cat and the Coup offers a clever solution. The player controls Dr. Mossadegh’s cat, guiding the Prime Minister from milestone to milestone in reverse chronological order, beginning with his death under house arrest in 1967. By any traditional measure, it isn’t much of a game: the physics puzzles are rudimentary, sometimes inscrutable, and only lightly interactive. The feline avatar may not have much agency, but it allows the player to unobtrusively skirt history, and the choice of that impassively omniscient creature evokes a soundly neutral perspective. Likewise, the haunting music of pianist Erik Satie strikes a perfectly ambiguous emotional tone. But otherwise, The Cat and the Coup fails to rise to that standard of objectivity. If you accept the proposition that good documentary stands on a tripod of clarity, depth, and impartiality, then this software is on shaky footing indeed.

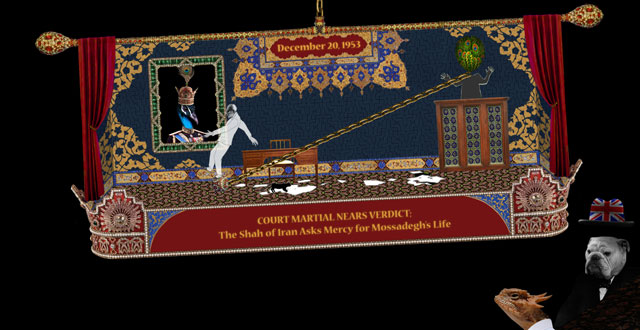

Ambiance, not rigor, is its strong suit. The sublime art style combines the aesthetics of Monty Python animation and ancient Persian miniatures. Layers of stationary and animated scenery and figures are illuminated with attractive arabesque patterns. But one has to wonder whose idea of a documentary it is, outside of Luis Buñuel. The use of surrealist symbolism to compress historical events can be an effective mnemonic, as when protesters literally push in the walls around Dr. Mossadegh, making you feel his confinement. But more often, it obliterates clarity. Presiding over the Prime Minister’s court-martial is a judge whose head is a peacock-feather-patterned balloon enclosed in a globular vase, which you bat off his shoulders so it rolls across the floor, still attached to his balloon-head by a chain. Dr. Mossadegh has to ride this rolling orb like a circus performer, smashing holes through the floor to the next scene. History becomes baffling.

Furthermore, the symbolic order imparts a moral bias that is much more human than cat. For example, alongside noble images of traditional Persian warriors looms a huge, fearsome pig in Western military garb with tank treads for feet. In fact, most of the Western characters have animal heads—President Truman is a rabbit, with a framed portrait of a British bulldog (Churchill, one presumes) in his office. Only Dr. Mossadegh is portrayed as human. After six scenes, the game abruptly ends, and he sleeps on a rising tide of oil, now moving forward in time as text scrolls by at an alarming pace. He arrives back in his body at the moment of death, closing the game’s structure in an elegant loop. Then he floats divinely into the sky.

One understands that the makers of the game wanted to distinguish their protagonist. The unabashed sympathy with Dr. Mossadegh may well be warranted, and the whole endeavor rings a timely note amid the Green Revolution and the Arab Spring. But this is the stuff of entertainment and polemic, not documentary, which should aspire to pin down facts without moral bias or prettifying filters. The Cat and the Coup is an intriguing, sometimes informative, and highly partial (in both senses of the word) point-and-clicker that everyone should experience for its bewitching environments and its creative riff on a pivotal moment in modern history—nothing more and nothing less.

It may be that documentaries and games are two great tastes that simply don’t taste great together, owing to their conflicting individual demands. But the real issue may be even deeper: that gaming involves a state of passive transfixion which should never be confused with proactive social engagement. Whether or not what we do in front of screens—however enlightening their contents may be—matters in any real-world way is a huge and open question. Respectable, traditional documentaries must answer it as well. For what are we actually doing when we engage with informative simulacra—say, An Inconvenient Truth—besides spending the carbon required to run them, while the world we’re learning so much about rolls heedlessly on?