This article is part of a series called Shut Up, Videogames, in which critic Ed Smith invites games old and new to pipe down, or otherwise. In this edition, he looks at the genre defying third-person action-adventure, The Order: 1886.

It’s no masterpiece—it’s the story of immortal knights fighting werewolves and vampires in Steampunk London. But The Order: 1886 (2015) is still more than videogame critics deserve. Its low review scores and petulant detractors are proof, once again, that games could never become art (whatever that would mean) because the people playing them and the people responsible for curating them simply wouldn’t allow it. Verily, no-one who reviewed The Order during its launch last year had a bloody clue. From complaining about its length, its closed, straightforward levels and its unwillingness to let the player explore, critics recited the same handful of complaints they throw at every game they can’t be bothered to consider. Even the praise levelled at The Order— “great atmosphere,” “solid gunplay,” “creative weapon design”—was recycled air. It’s a sorry state when a game as uninterested in tradition and form as The Order can only be viewed through the antique framework of magazine videogame review. And when critics have grown so smug and apathetic that only brazen, moist-eyed complaisance like Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (2015) can get them to think—even for a second—about what they’re saying.

The Order cannot only be viewed through the antique framework of magazine videogame review

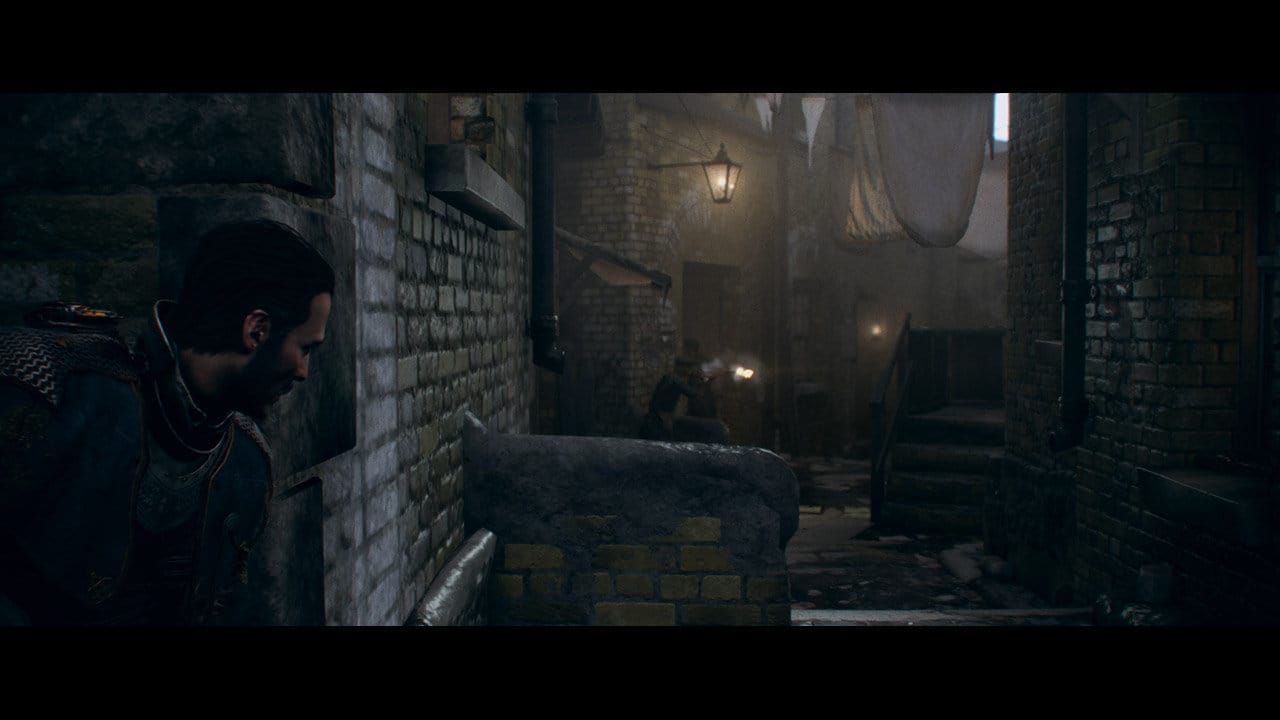

There are so many fantastic moments in The Order: 1886. The one-on-one knife fight with the alpha werewolf. Standing over the airship ballroom, identifying assassins disguised as guards via the discrepancies on their counterfeit uniforms. Igraine is a fantastic character. The ending, considerably more muted and sober compared to what could have been, is a rare example in the gaming industry of restraint and sombreness over spectacle—not that the game struggles with spectacle. Ready At Dawn Studios, quite rightly, picked up an award from the Visual Effects Society, and I can see why. Where so many games conflate visual lustre with colors, wide open spaces and fantastical expression, Ready at Dawn is fascinated by cold, old interiors. I’ve spent a lot of my life inside English churches, and the great halls at country estates, and the same woody smell and fragile silence that hangs heavy in those places permeates The Order, especially during scenes around the Knight’s roundtable.

At times, The Order lapses into rote third-person shooter or horror game style but largely I’m impressed and relieved with how defiant it remains throughout, refusing to emulate the many other games based around guns and monsters. I’ve never played anything like The Order: 1886. And I don’t mean in the dumb, false Saints Row way—this isn’t a sandbox game where every wacky, supposedly idiosyncratic idea has been researched and focus tested, and is remarkable only to the kind of people who think the Joker from The Dark Knight (2008) is a complicated character. I’ve bemoaned in this article the use of clichés, so forgive me in advance, but The Order is a true original. Videogames are often created to slot neatly into genres—shooter, horror, “interactive story.” But like its antagonistic Hybrids, The Order refutes easy classification. That wilful lack of straight identity meant, essentially, it was too complicated for game critics, not the individuals, mind you—they’re smart people—but the field in which they work.

Individuality and videogames are a square peg and a round hole. We credit work to studios. We judge all games by the same or similar criteria. We refer to artists with the dehumanizing titles “developer” and “designer,” or even worse, “dev.” The lack of diversity in the videogame industry is visible from space, but beyond precluding women, gay people, and people of color, there’s a surreptitious effort, smuggled through customs under the rubrics of consumer friendly or matter-of-fact writing to homogenize and compartmentalize videogames. Everything must have a term and a place. Everything must fit at least some of our pre-existing notions about what games are or should be. So when a game joyfully undermines the conventions of so many genres, a game like The Order, which cannot be easily separated out or discussed like one would discuss a household appliance, it goes misunderstood and forgotten.

Exactly what’s caused this opposition—an opposition expressed through unremarkable often non-confrontational language but an opposition nonetheless—to heterogeneity I could only speculate. It probably has something to do with games still being created by white men, to be reviewed by white men and then either bought or despised by white men. I’d say the gaming industry’s homogeneousness begins at race and gender but extends beyond those things, leading to a culture so blinkered and small that any contrary ideas, even if they come from white, straight, Western guys, must be chased away. We’ve delineated the independent space as suitable for exploration and experimentation, but big budget games are simply not allowed to effectuate and change. That would challenge our stratifications. It would fuck with our minds. Hence the magic of The Order: 1886. Hence the tragedy of its reviews. Something is going on. And until it’s identified and challenged, great, inventive, big budget games will continue to go unsung.