The “Cantina Scene” in Star Wars is still commonly used as a quick-hand reference for weirdos, freaks, and peculiar has-beens. A smarmy guy in a suit tried to offhandedly insult me a few years ago by saying that I looked like I “belonged” in the Cantina Scene—with its alien pirates and snorting alcoholics—to which I replied, “Thanks,” and smiled, much to his apparent confusion.

That minutes-long scene has been blown up, as with everything in Star Wars, into part of the popular lexicon. It’s used often as the butt of a joke, as a disparaging comparison, to express having an issue with the mere presence of the sub-normal. Rarely is it engaged with positively, to spread its known weirdness and extraterrestrial influence further into the realm of subcultural rapt. Imagine the species of outlandish sci-fi that would root itself in that and blossom throughout creative media if so.

No need, as that’s precisely what Tom van den Boogaart and Jake Clover have done, by each making a videogame world that uses the oddities of the Mos Eisley cantina as a starting point. Boogaart’s Bernband and Clover’s Hernhand have both been inspired by the other’s 3D game, and are both of the same city-exploring concept, but they each bear the distinct marks of their author.

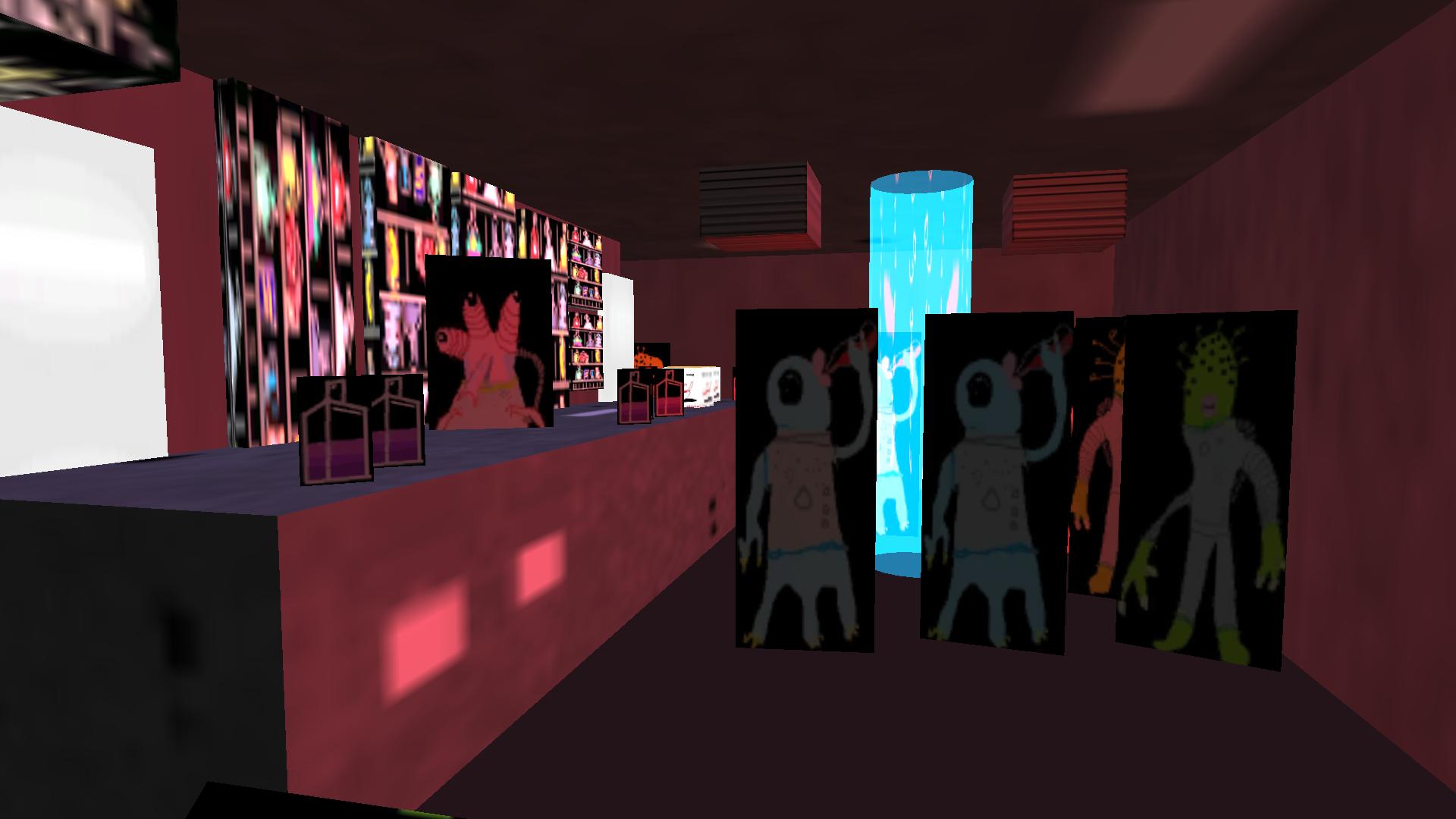

Boogaart’s Bernband is a highly accomplished multiplex of connected dark future-city scenes. At the upper echelons the bright lights and high-speed traffic blends in with the exotic sounds of the commoner’s live entertainment as a noise that drifts between the waddling pedestrians. There are bars, theaters, an empty church, a side street takeaway, a dead-end DIY store; all waiting to be discovered. On occasion, televisions murmuring news reports and flashy documentaries give the impression of a larger world.

You mingle with an entire population that burbles and squawks, that sucks on liquid substances from unknown protrusions from their face; it’s all very overwhelming and the blurred pixels and stark lightning reflect that.

Venturing around this city, while unusual, was a familiar task for me. In each new city that I step into—Berlin, Johannesburg, Paris, Krakow, San Francisco—I deliberately walk for hours in a single direction getting lost. I dare to go down allies, connecting side streets to roads, triangulating landmark monuments and unique graffiti, following the smell of a river to find a bridge. It all goes toward getting the “feel” of a place, including its street culture, manners, the condition of buildings, how crowded it is. Somehow, Bernband‘s city is interconnected in a way that allowed me to perform the same task; it feels that believable, like a proper bizarre city.

So, yeah, it’s fun to get lost inside Boogaart’s metropolis, and also to escape the bustling streets by falling into ventilation shafts and walking down industrial alleyways. Stand alongside a guy staring into a fish tank. Look up at the criss-crossing pipes. Sit on a pew and watch as somebody’s child plays their instrument in front of an audience for the first time.

Then, turn a corner and emerge in underground scenes that are inhabited by even weirder folk: bright green clubs of tentacled dancers, garage parties of teenagers nodding to gangsta rap about the size of wheel rims. All walks of intergalactic life found in their own holes of a sprawling, active city.

Clover’s Hernhand has the same structure as Bernband, although the focus on rumbling, terrifying micro-sounds makes it feel even more alien. Spaces range from the empty and disquieting, to busy and cramped. The automatic doors are the size of walls and resemble the patterns of a lizard’s skin more than an access way. Rather than a whole highway of cars whooshing by, Hernhand just has a lone hover-van circling the air as if it’s performing a strict surveillance routine. You don’t feel welcome here, nor like you can blend in at all, not like in Bernband.

It’s the kind of sci-fi world in which you don’t know whether it’s safe to keep moving forward or not. Everything seems to speak in its own harsh language—wall-mounted hand scanners, the garish moving patterns of the walls, the creatures that made a home between two trashcans. If Bernband captures our strange fascination with the Cantina Scene, then Hernhand exposes its disturbing underbelly of roughnecks and creepy stares. No surprises that Clover lists one of the influences for the game as “public toilets.” (Once, to illustrate his love of muffled sounds, Clover said, “sometimes I stand in public bathrooms and listen to the sound of the hum.”)

While Hernhand feels just as alive as Bernband, it’s less a unified city and more of an abstract nightmare vision of a megalopolis. The underground sector here isn’t a delightful find, it’s inescapable: you fall down a large metallic shaft to the sound of evil laughter, landing on a flat plane with a single cluster of skyscrapers, all of it surrounded by a void. Mingle with the vicious, or the other option is to drop off the sides and fall forever.

Bernband and Hernhand give us a look at what the darker, more peculiar side of popular sci-fi could look like. They’re videogames that imagine Star Wars without the humans and the heroics. They ask the questions, “What if Star Wars focused on the aliens that spoke in a language we can’t translate? What do their worlds look like?” These are just two of many possible answers.

You can download Bernband for free on Game Jolt. Hernhand can also be downloaded for free on Game Jolt.