It’s no secret that Metal Gear Solid is a montage of the strange and bizarre. From nanobot-powered vampires to cyborgs with white blood, there’s no shortage of head-scratching moments amidst all the sneaking around and monologuing. But, now in its 17th year, Hideo Kojima’s magnum opus seems to be rolling towards its apotheosis by foregrounding its creator’s dark and often troubling preoccupation with the human body and the basic dignity of humanness.

Although many games have “bodies” and many games involve stabbing, shooting, slicing, and dicing them, few series have gone so far out of their way to showcase, alter, mangle, deform, transform, and violate them as Metal Gear Solid. Despite the series ostensibly being about nuclear nonproliferation, Kojima has never shied away from making sure that you knew at the core of Metal Gear Solid was a soft, fleshy protagonist in a world full of soft, fleshy people. Kojima delights in tormenting these characters, and over the years this theme has only escalated.

From early in the series, Kojima works to make his characters simultaneously more and less than human. One way that he does this is by stripping away characters’ names. In Metal Gear Solid you play as Solid Snake, not John Protagonist, and you fight against the likes of Sniper Wolf, Psycho Mantis, and Vulcan Raven. But their names haven’t simply been replaced; these names inform the persona and appearance of each character. Sniper Wolf hangs out with actual wolves, Psycho Mantis has a thin, gangly physique, and Vulcan Raven has a massive Raven tattooed on his forehead. By animalizing them in this way Kojima removes much of their agency. Their whole lives and backstories are dictated by a basic human identifier to the point where they can have no control over it.

Snake Eater exemplifies a different aspect of this. In naming the villains after emotions, Kojima reduces them to their basest feelings, feelings that overwhelm and control them. In doing so, the Cobra Unit is again both more and less than human. The members of the Cobra Unit also have unique physical attributes or have undergone some kind of trauma that makes them unique. For example, The Fear has a forked tongue and reptilian eyes. The Fury was horrifically burned and only appears in a protective full body suit. The Pain was also heavily scarred by his trademark weapon, bees. On the battlefield they are nearly unmatched, but the whole point of their defection is that they’ve been treated as only tools of war by the US government, and not as people.

This idea is taken to a nightmare end in Guns of the Patriots with the Beauty and the Beast Corps. Here, the characters are encased in full body suits that exaggerate their animal namesakes while reducing their human qualities. Laughing Octopus uses the tendrils to move and attack, barely using her own legs. Raging Raven attacks mainly through the use of her wings. Crying Wolf is perhaps the most shocking example of this, as her suit forces her to move on all fours and hunts by scent. Here the idea of reduction to animals and feelings are merged, a near-final debasement of their basic humanness. The Beauty and the Beast Corps scream and yell during battle, many incapable of intelligible speech due to the severe PTSD that they have experienced. Their names and identities are completely wrapped up in the singular task of war on Solid Snake.

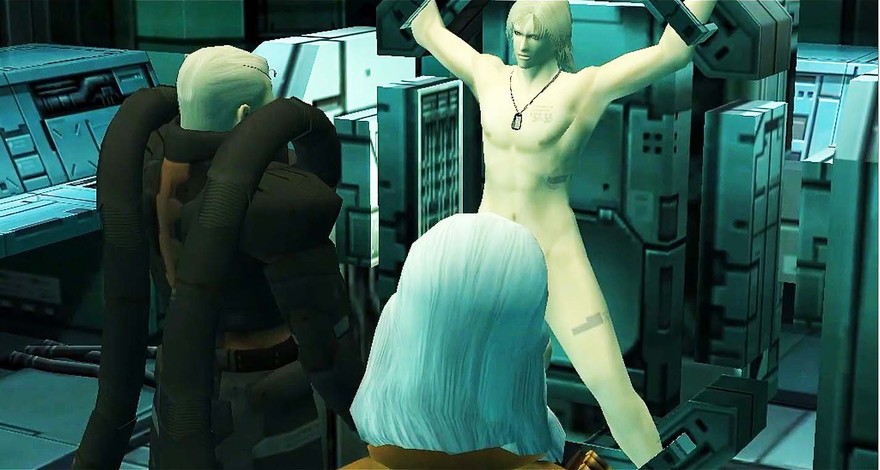

But that’s not the only way that Kojima breaks down the human body. He also frequently tortures and strips his characters. The Metal Gear Solid games each feature a sequence where the main character is tortured either topless or naked for an extended amount of time. In the first three games the player character is completely helpless and whether or not they pass out has no real bearing on the game as a whole. Unique to Snake Eater is the fact that the player is not tortured completely naked. On the surface this nudity is somewhat arbitrary and doesn’t add much to the story. However, this does directly speak to the theme of nuclear nonproliferation, albeit in a more obtuse manner. In these sequences both Snake and Raiden are reminded of their vulnerability despite their previously demonstrated strength. The torturers are also always on the side of the power seeking to gain nuclear autonomy. This represents an ultimate kind of power shift. No matter how strong a nation or army becomes it can all easily and instantly be wiped away one of these nuclear weapons in the same way that Snake and Raiden both grow stronger and stronger until brought low by an atomic enemy.

Snake Eater presents yet another angle on Kojima’s body politics. Instead of only torturing the main character, he also partially blinds Big Boss when Ocelot accidently shoots out his right eye. Also unique to Snake Eater is that it’s the first time that the player does not have to mash a button in order to endure the torture—Colonel Volgin batters away at him and both Big Boss and the player are simply along for the ride. Although not naked, the player and the character are put in a position by Kojima that is more helpless than at any other time in the series. Tellingly, Ocelot remarks that Volgin’s torture “is really not that bad. It’s the ultimate form of expression.”

This scene sets up an element that is shockingly apparent in The Phantom Pain but also present elsewhere in the series: amputation, augmentation, and prosthesis. From the trailers it’s clear the Big Boss has had his left arm amputated and replaced with a weaponized prosthetic. But although the title is an explicit reference to the phenomenon experienced by amputees it goes deeper than that. The word amputate itself comes from base words meaning very literally “to prune around,” and the series as a whole is very much one where distinctly human elements are pruned or culled. Big Boss previously loses an eye and his genetic information, Raiden loses his entire body from the upper jaw down (which is spurred by his belief that his girlfriend Rose has miscarried), The Boss and Olga Gurlukovich both give up children, and Solid Snake essentially has 40 years of life taken away due to accelerated aging. And that’s not an exhaustive list either. The Metal Gear Wiki has 8 pages dedicated to amputees alone.

All of this bodily loss, separation, and augmentation are reflective of the main threat of each of these games: the inhuman, the abstract threat presented by a world with a nuclear gun pointed at its head. Solid Snake makes it his life’s mission to fight giant metal robots that fire nukes and in doing so takes on a literal embodiment of the military industrial complex. Similarly, Big Boss, the Boss, and a slew of others have fought that same military industrial complex by building giant metal robots that fire nukes. Each of these distinctly human losses against a distinctly inhuman enemy has a great personal cost. It serves as a reminder of the muscle and bone characters struggling against massive systems which dwarf them and debase them in order to maintain a social order.

This debasement in order to maintain the status quo is never more apparent than in Ground Zeroes. In a moment that caused many to wonder if Kojima had crossed an invisible, unspoken line, he finally turned a living breathing human into a weapon by inserting multiple bombs into the body of a young woman in an attempt to kill Big Boss. While the weaponization of humans is by no means new to the series, the gruesome and arguably senseless way it occurs take Big Boss from a sympathetic character to one who goes on to threaten the world in the later games. This war on humanness also appears in the latest trailer of The Phantom Pain, when an unknown narrator says “race, tribal affiliations, national borders, even our faces will be irrelevant.” Combined with Big Boss’s description of what the Patriots were trying to achieve from Guns of the Patriots, a world governed by systems and norms that created peace, one can see how the irrationality of an embodied human might be a threat.

What can be seen from this constant thread of debasement, harm, loss, and replacement is a struggle to maintain one’s humanness in the face of an inhuman enemy. The series is full of heroes who give up their essential humanness in order to better participate in the war. Kojima’s punishing and mangling of bodies is more than for gruesome effect, it’s to continuously push other more grandiose and apparent themes of the series. The strange, dark, and often troubling body politics of Hideo Kojima are not distinctly different from other directors like Cronenberg, Barker, or Fincher. It’s there to remind us that soldiers are flesh and bone people with ambitions, hopes, and dreams. It’s there to remind us that weapons of mass destruction are the ultimate dehumanizer, the ultimate agency removal device. It’s there to remind us that the road to hell—or at least Outer Haven—is paved in good intentions.