Super Mario 3D World and the joys of jumping in videogames

The impending release of Super Mario 3D World ensures that over the holidays, gamers of all ages will be leaping, floating, and cat-scratching their way around what’s sure to be dozens, if not hundreds, of virtual playgrounds. From the trailers and previews, it looks as though Nintendo has crafted a game meant to be a multiplayer frenzy, an aim which definitely lines up with their “family fun machine” design for the Wii U.

Despite the smorgasbord of new quirks and gameplay treats that Nintendo is offering up with this latest title, however, I can’t help but be relieved by Shigeru Miyamoto’s recent reassurances that there might be more Super Mario Galaxy in the future—not because seeing Mario in a cat outfit isn’t cute (it is), but because what I love about the red-hatted plumber, more than anything, is how he has changed how I think about the simple act of the jump.

Each entry in the Mario series has been an experiment in transforming the act of jumping.

Jumping has always been essential to Mario’s identity. Before Nintendo of America christened him with the name of its warehouse’s landlord, it was his sole defining characteristic. In the original Donkey Kong, he was simply “Jumpman.” The man who jumps. There is a reason that, in Super Mario RPG, the only means a mute Mario has to prove his identity to scores of disbelieving NPCs is by displaying his jumping prowess.

In controlling Mario, we have been given a cornucopia of reasons to jump: to vault barrels, to squash goombas, to hit question blocks. Jumping is Mario’s primary method of interacting with his environment. Those of us who have played many platformers may take for granted how deeply ingrained Mario’s jump is in the grammar of videogames. (“How do I kill these enemies?” “Well, have you tried jumping on their heads?”)

But in much the same way that Mario has been central to establishing the jump as an essential utility in games, he’s also been at the forefront of liberating the jump from its utilitarian origins. Each entry in the Mario series has been an experiment in transforming the act of jumping, and the most successful and iconic of his outings have always turned a jump into an expression of joy and freedom.

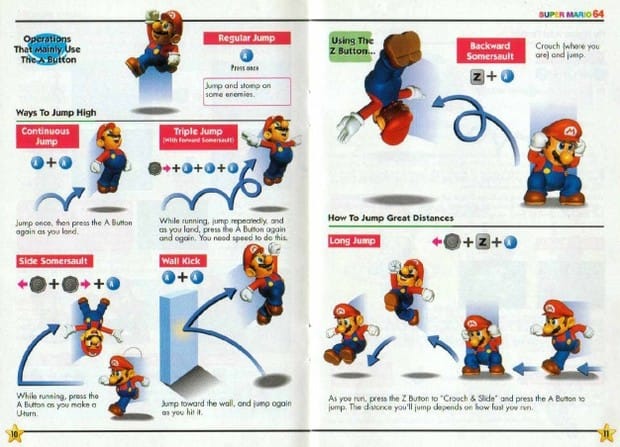

There’s probably no better example of this than Mario’s transition into the third dimension. Super Mario 64 offers players such a myriad variety of jumping abilities that it’s almost overwhelming: the jump, the triple-jump, the long jump, the backflip, the side-somersault, the wall-kick… not to mention the somewhat undignified (and yet still iconic!) “ground pound.” Each of these different jumps has a utility, to be sure, and there’s immense pleasure to be gained in properly utilizing them when they’re called for. But Super Mario 64, with its wide-open areas, invites you to jump simply because you can. Because there is an inherent joy in jumping.

When you attempt the triple-jump, Mario’s vocalized exultations are meant to mirror your feelings as the player. In a different medium, the notion of these shouts of joy being memorable or recognizable might be goofy (“Hoo! Woohoo! WAAHAAAA!”), but they correspond with a player striving to leap blissfully higher and higher, and everyone who’s played the game remembers them. Mario tempts us with the fantasy that we might jump and jump, each time higher than the last, until ultimately we launch ourselves into flight. It’s a moment that has lost little of its effect in the seventeen years since the game first launched.

Other Mario titles add their own twists to the sensation of leaving the virtual ground, but the most successful and cherished have always been those that tap into some primal urge of physical expression. Super Mario Galaxy is lauded for its superb level design, which breaks free from many of the imagined constraints of previous platformers, but the sensation that I’ve retained, six years after playing it, is the feeling of taking a running leap off the edge of a world–of hurling Mario into the boundless void of space, only to find him slung back around onto the opposite face of a planetoid and landing feet-first on the ground.

Mario tempts us with the fantasy that we might jump and jump, each time higher than the last, until ultimately we launch ourselves into flight.

Because games allow a player control of an avatar, they’re able to vicariously communicate physical sensations in a way that’s much more effective than any other medium. In no other medium can actions be performed by the medium’s audience; watching someone in a film narrowly make a leap across a chasm is anxiety-inducing, but an audience member doesn’t feel that leap in the same way that they do when they have a controller in their hand (and are responsible for that jump’s success or failure!). That responsibility forges a connection between player and avatar, and while it has its origins in the jump-as-utility, it fully extends into the realm of jump-as-expression.

And so many developers have taken what Nintendo pioneered with Mario and gone (pun fully intended) leaps and bounds further. Neither a film nor a book (nor any written words of mine) could fully communicate the feeling a player experiences when they sail skyward in Jumping Flash, for example. An oddball experiment among its FPS brethren, Jumping Flash allows the player a colossal three-stage jump, shifting the camera toward the ground so that they can plot their re-entry as they plummet hundreds of meters back to the stage. The game’s protagonist, Robbit, shares Mario’s ability to dispatch enemies by dropping on their heads–and watching the blocky, polygonal creatures rush up to meet the camera and explode in a shower of sparks and coins is immensely satisfying.

Plenty of games since have incorporated the jump as a fundamental element of the power fantasy they offer the player. Think of Crackdown, which gives us Superman’s much-vaunted ability to leap tall buildings in a single bound–and then allows us, in a manner very unlike Superman, to gun down half a dozen thugs in cold blood before our feet hit the pavement. Crackdown wears its nature as a power fantasy as a badge of pride, and though that manifests itself in a number of different ways–from being able to take a hundred bullets without dying to being able to karate-kick an oncoming semi truck–the most joyful thing about the game, the thing that gives players both power and freedom, is the ability to leap hundreds of feet into the air, our avatar’s arms slowly cartwheeling as we careen skyward.

Watching trailers for Mario’s latest, the upcoming Super Mario 3D World for Wii U, I have been contemplating whether it has anything new and exceptional to offer in the way of jumping. The new “Cat Mario,” prominent enough in the game’s design to warrant being included in its logo, offers players the ability to scrabble up walls and down-kick diagonally (something we’ve been doing in games since at least the days of the Ninja Turtles). I wondered briefly to myself why that particular combination felt so familiar until I remembered how much time I’d spent causing havoc in the simulated Steelport of Saints Row IV, which takes the power fantasy of Crackdown and carries it to virtually inappropriate extremes. Saints Row has fine-tuned its jumping mechanics to masterful effect: simply requiring the player to hold down the jump button and concentrate power before rocketing into the air adds a moment of anticipation which makes the whole effect positively delicious.

Games in three dimensions have come a long way since Super Mario 64, and Mario no longer has the role of defining the possibilities of the virtual space in the way that he once did. It’s satisfying to see, however, the ways in which games have played with the gift that the Jumpman gave to them, and to know that there are now a plethora of games which allow us to jump for joy.