Memory and videogames is a complicated crossroads. Not least because there’s a minimum of three types of memory meeting at this particular intersection.

The most obvious one is personal memory: we remember the games we played over the years and attach emotions, physical locations, the music we were listening to at the time, and more to them. The second might be called technical or virtual memory, referring to the memory that videogames themselves contain. This is the RAM (random-access memory), the ROM (read-only memory), the immaterial saved data on hard drives and memory cards of old. Third is the cultural memory of videogames and it’s this one that is suffering the most right now as it determines which games are worth remembering in the public sphere and in relevant communities. This is enacted through a selective nostalgia; through the HD remakes, through the new games with “retro” aesthetics, through the articles and books written about games and their history, through the collections in museums and galleries, through the software that is created such as DOSBox that allows older games to be playable on modern hardware.

These three types of memory around videogames don’t keep to themselves either. They merge with each other across different debates and actions. When a teenager wrote that they found their dead father’s ghost inside Rally Sports Challenge (2002) on the original Xbox they didn’t mean it in a spiritual manner but a virtual one. The ghost was actually a saved replay of their father’s best race time on that track, the digital imprint of his actions recorded and preserved for as long as the hardware doesn’t retire: “i played and played, and played, untill i was almost able to beat the ghost. until one day i got ahead of it, i surpassed it, and… i stopped right in front of the finish line, just to ensure i wouldnt delete it,” they wrote. True or not, this story is plausible; it could have happened to someone or it might happen in the future. It’s a merging of the personal memory and virtual memory of videogames.

When games and culture writer Leigh Alexander wrote that videogames have a “memory problem,” she referred to their technical and cultural memories. The issue she writes about spring-boarding off a warning from Jason Scott of the Internet Archive who said that a lot of videogame history is going down the plughole. A lot of software is discarded once it gets old and that makes Scott’s job of retrieving it for preservation either very difficult or impossible. Plus, nowadays, it’s not uncommon to see an online multiplayer game wiped from the Earth after only 18 months, everything that happened inside its virtual walls lost forever.

This erasure happens elsewhere too; websites shut down, documents are lost, games confined to arcade cabinets are entirely wiped out. Konami removing the P.T. (2014) demo after cancelling Silent Hills is also a prominent example of this. But P.T. is also an exception as it has been remade by fans and continues to be imitated in upcoming horror game titles. It’s a game that people have decided should be remembered. Most games that are lost don’t get that luxury. This is cultural memory’s dark side in practice, it all too happy to let certain games and materials around them (articles, essays, videos, and so on) be forgotten.

But these games aren’t entirely lost. They do still live on as traces inside personal memories. And if that’s the case then it’s possible a fumbling description of them emerge in the subreddit “Tip of my Joystick.” It being a videogame-specific offshoot of the “Tip of my Tongue” subreddit, Tip of my Joystick is a place where people can get help in re-discovering games they have played before but don’t know their title and can’t otherwise find out what they are. It’s frequented by game creator and critic Noyb as he enjoys being able to test out his knowledge of obscure games while putting it to good use. But it’s a two-way relationship, as Tip of my Joystick’s list of solved games—that is, forgotten games that have been identified—often teaches him about games he has never heard about too.

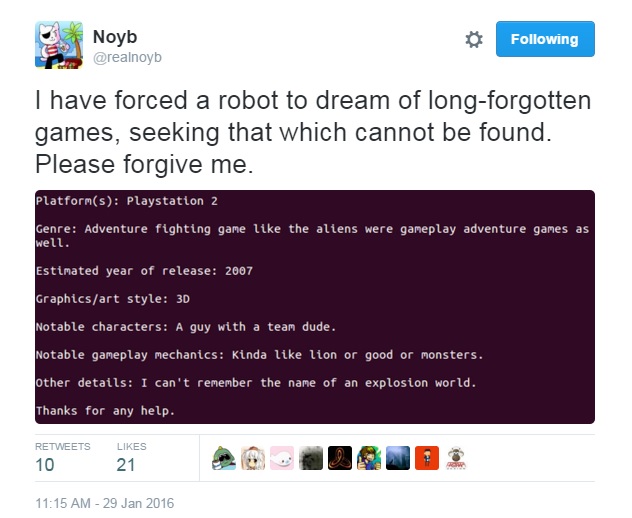

Noyb’s time spent on Tip of my Joystick has led to a small side project. He recently discovered Andrej Karpathy’s char-rnn, which is “the same neural network-building tool which made news last year when Reed Morgan Milewicz used it to generate Magic the Gathering cards,” according to Noyb. Char-rnn tries to learn patterns in sequences of text. And so it is able to work with the set format that posts in Tip of my Joystick are instructed to follow (platform, genre, year of release, and so on). With it, Noyb was able to write an ad hoc NodeJS program to scrape two years worth of Tip of my Joystick posts for char-rnn to work with. The resulting bot is then able to generate written mimicries of these posts as a stream of abstract descriptions of forgotten games.

Noyb admits that his bot is only building on the work of others. Darius Kazemi’s annotated code for the Twitter bot “Two Headlines” was very helpful apparently. But the curiosity behind the bot is all his. Noyb says he’s become fascinated with how the bot has managed to capture “the uncertainty of the original posters and plenty of gaming jargon, all of which enhances the sense of apophenia when reading a generated post.” He has cherry-picked some of the bot’s better output and shared it on Twitter but he’s still in the process of training it—it still struggling with long descriptions—and so he’s waiting before doing something more public with it. That might be sharing it as “a checkpoint file which can be run by other users of char-rnn, or perhaps generated in bulk and repackaged as a Twitter bot.”

The relevance of a bot that generates descriptions of forgotten videogames has not escaped Noyb, it of course being a combination of personal and cultural memory. That feeling of grasping at a faded memory, distant from us due to the blurring of time, is what Noyb’s bot emulates. It’s something that a lot of us are probably familiar with. But, beyond that, it also evokes the loss of a more offbeat and heterogeneous videogame history that isn’t bordered by the usual cast of low-poly platformers and sprite-based RPGs. This is something that Noyb is trying to direct the bot towards, more and more.

“It is inspiring how many games are coming out every day now—commercial and freeware, made for consoles and computers, audiences niche and broad—and this means in part that there are more and more games we collectively forget,” Noyb says. “The games you played as a child which never entered the discourse, the games which never bubbled up out of development forums or game jams, the games never profitable or popular enough to be ported to modern systems.”

His hope is for his bot to approach this breadth with descriptions of games that never existed but theoretically could. Games that match descriptions Noyb shared with me, like: “The player character was a sewer,” “a bunch of time watching a castle,” or “you had to look like a part of a demon that was taken.” Right now, though, in its current work-in-progress state, the bot only reflects the state of the cultural memory around videogames: “much of its current overfit output feels like little more than a hazy dream of reprocessed nostalgia, endless variations of the same themes,” Noyb says.

Hopefully, he can change that so that its output curves towards wilder descriptions, speaking of the potential creative wealth of videogames. Unfortunately, this mechanical tweaking of memory won’t have any direct or likely even an osmotic effect on the public consciousness around games, even though it’s exactly what it could do with. Hopefully the important plea of Jason Scott, the internet archivist, hasn’t fallen on deaf ears: “Please save your history … be a part of tomorrow, because tomorrow is going to learn from you.”

///