This article is part of PS2 Week, a full week celebrating the 2000 PlayStation 2 console. To see other articles, go here.

This article contains spoilers for Shadow Hearts, Shadow Hearts: Covenant, and World War I.

///

Several famously grim prophecies were recorded in the run-up to World War I. “The lamps are going out all over Europe, and we shall not see them lit again in our life-time,” said Sir Edward Grey, turning a phrase better remembered now than his own role in the disaster. On the first day of the war, Henry James wrote privately of “the plunge of civilization into the abyss of blood and darkness.” And over a decade earlier, military theorist Jan Bloch had seen the shape of the conflict: a “great war” fought in trenches, a “catastrophe which would destroy all existing political organizations…any attempt to make it would result in suicide.”

But no real doomsayer went over the top in quite the way Albert Simon, the villain of the 2001 JRPG Shadow Hearts, does. Standing ramrod straight in his formal cravat, top hat, and little white gloves, he’s a caricature of what Samuel Hynes called the “Edwardian afternoon,” which ended when the war began. In an alternate-history 1913, the game’s occultist heroes chase Simon from his gore-caked laboratories in Kowloon to dive bars in Prague. When they finally catch up in Wales, he reveals the “terrible vision” that drives him: “I can see the future in store for this world…earth will overflow with the screaming of the dead who know not yet their fate. An iron behemoth shall rise and in a flash, countless lives will be snuffed out. A hopeless future!!” To prevent this, he explains, he’s decided to summon one of the “Outer Gods” from “the M72 Nebula” to remake the planet.

Simon’s plan sounds, at best, like it might improve Bloch’s scenario to the status of “assisted suicide.” But as far as reasons to reformat the world go, “disquieted by industrial warfare” is not bad. Simon’s announcement embodies the strange appeal of the Shadow Hearts series, which dabbles in ghost stories, pro wrestling, political science, dogfighting, distrust of the Vatican, Japanese militarism, secret societies, and JRPG tradition, but is loyal in the end only to the principle of staying weird. By going sci-fi in its last hours, the game escapes the gravity of the political maneuvering it used earlier to set off its cast of Dutch, Japanese, Chinese, and English characters. Our protagonists can’t line up for turn-based battle against the Schlieffen Plan, but they can fight the “Meta-God” in space.

It’s the last of many swerves in a long and eccentric adventure. Shadow Hearts begins in Manchuria, where a Chinese warlock is absorbing local spiritual powers to clear the way for a national invocation—we’re told that he once tried to “blow Japan to bits” with a similar ritual, which left half his body warped and reptilian. The player’s party trades insults with his psychic projections while crossing China on trains, rusty biplanes, and a fishing trawler that looks less seaworthy than some vessels found on the ocean floor. In the second half of the game, the pattern more or less repeats in Europe with Simon as the antagonist. The game’s unusual eye for locations means your next destination is usually a mystery: you take in not just world capitals and mystical fortresses but small-font locales like Dalian and Rouen. (The sequel, Shadow Hearts: Covenant, is perhaps the only RPG to include a section in Southampton.) Some of the best stops, like the fortress in Hong Kong and an evil doll’s home in England, are hidden away and easily missed.

It’s a world of disparate horrors. There’s a town in Shadow Hearts where the spirits of domestic animals masquerade as the human masters they ate: “You don’t have to worry about your manners so much here…it won’t change the taste of [the] meat,” the mayor, a “Cat Lady,” tells you. In London, the owner of an orphanage melts down his wards into a “soup of life” to revive his long-dead mother. In Prague, a witch reaches out from the mirror in a women’s bathroom to rip the life out of unwary souls. At one point, to explain a ghost’s convoluted beef with the villagers of Dalian, the game launches into a grungy narrated cutscene that amounts to a campfire story (“the door opened….creeeeaaaakkkkkk….”) and runs nearly eight minutes, but feels like it could easily continue for the rest of your life. There’s nothing remotely like it before or after.

The hard-heartedness of the first game, which coolly dispatches minor characters throughout, gives its ghost stories some unexpected bite. (It has two endings, but the sequel picks up from the bad one.) So too does the designers’ oddly sexual approach to monster design, which is on display in both games: Janus-faced Peeping Toms hang upside down in midair; hovering eyeballs shudder with pleasure when casting spells; pale cylindrical men with backwards-facing heads patter over on stubby feet, then bend toward you to reveal a prehensile penis-tail reaching out from their navel. A monster log—that is, a diary, not an evil log that lives in the woods—describes each foe with clinical detachment: “Otherworldly snake that swallowed a pregnant woman whole and absorbed the fetus into itself. The human half is in agony and screams constantly.”

There’s something to admire even in the pre-rendered, vaguely regurgitated-looking backgrounds and hammered-flat faces of the first Shadow Hearts, whose grody visuals are inextricable from its weird-fiction atmosphere. When Shadow Hearts: Covenant arrived in 2004, it brought with it fuller 3D backgrounds, a somewhat mobile camera, and bumpier faces. Yet these technical improvements led to plain interiors and an outpour of broad, repetitive cutscenes that can be unpleasantly reminiscent of Kingdom Hearts. (Particularly in an interminable mid-game episode involving Anastasia and Rasputin, which plays like a second-rate adaptation of the Don Bluth movie.)

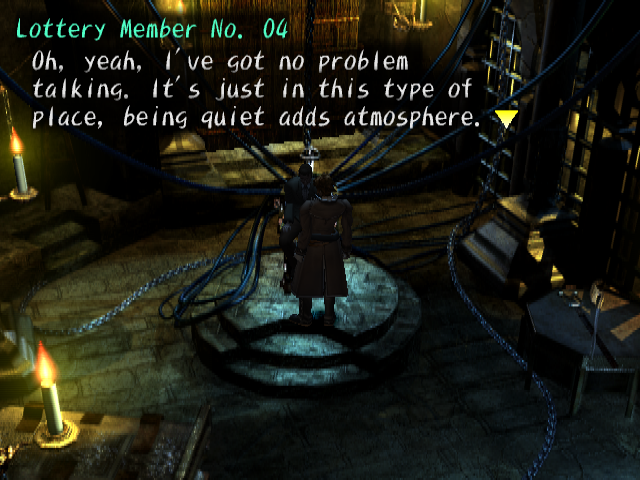

The Judgment Ring, the series’ singular timing-based battle system, is one piece of technology that gets stranger and better in Shadow Hearts: Covenant. In both games, you must stop a spinning arrow on the colored “strike zones” of a dial before your character can attack or use an item. Missing a zone means losing a turn. In the first game, the routine does eventually become second nature: hit X at 3, 7, and 10 o’clock to nail the hero’s combo every time, even when the strike zones are invisible or status effects shrink the ring. But Shadow Hearts: Covenant goes wild with the concept, letting you stack characters’ attacks into brutal combos that require upwards of 10 successful ring hits, but scuttle everyone’s turn if you miss any strike in the sequence. The combo system turns battles into wagers, mirroring the Judgment Ring’s use as a gambling game in towns throughout the series. The greatest secret society in Shadow Hearts is comprised not of its antagonists but the hidden “Lottery Members” in each city, who bestow gifts on anyone who can win their ring-spinning carny games.

Does Shadow Hearts have anything to say about World War I—the futility of the conflict, the great waste of life, the end of Henry James’s notion that we lived in a “gradually bettering” world? Not really. The setting adds to the game’s novelty but doesn’t take it over. Ideas from history wander in and out of a digressive narrative, mingling with concepts swiped from Final Fantasy VII and Lovecraft, with elaborate metaphors for depression and badly dated sexual politics and bizarre meta-gags. You can find someone pontificating about the “bitter battlefield of men,” but it’s the Great Gama, and he’s talking to a vampire pro wrestler about the ring.