In the first few hours of The Division, you will be bombarded with phone recordings, resources and consumables, an overwhelming litany of damage numbers and weapon mods. It puts you in such a constant state of information overload that after a while it’s easier to ignore everything but the essentials. You come to assume that, as long as you are shooting, progress is being made. Stalking the cold streets of an abandoned New York City, running missions to collect supplies for upgrades, assaulting strongholds and rescuing hostages, the rhythm of the game is a familiar one. It’s one that has slowly been developed by Ubisoft over what is now a decade of open-world game design, one that colors a map with a rainbow of icons and symbols, the fiction merely a dressing on top. The numbness that grows out of this overload is also a process of occlusion, slowly divorcing your experience from the troubling fictions that make up The Division’s premise.

That’s why I was surprised when one little statement stuck with me, when all the who’s-who and what’s-what seemed to slip away: “The purpose of the Division is to secure the city and ensure the continuity of the government.” It’s a seemingly innocuous statement, hidden as it is among other loading screen tips about grenade types and upgrade nodes; another bit of information bloat in an already bloated game. Perhaps it’s because the statement is so strange; “ensure the continuity of the government.” Is that really what I have been doing in my role as a Division agent—Ensuring presidential control? Helping to form an ad-hoc dictatorship? It’s a statement that started to get to me, to get under my skin. As I ran back and forth, killing and collecting, I started to wonder what this game is really about.

When I began trying to unpick the confused web of real-world references and speculative fiction in The Division, it was this statement I kept coming back to. It’s perhaps because it is an appropriation, a direct copy of the wording of Directive 51, created and signed in 2007 by the president at the time, George W. Bush. Mostly classified, its small public portion regards government actions in the event of a “Catastrophic Disaster,” and is designed to cement presidential control until the all-clear has been called. For The Division, it is a key jumping-off point for its central conceit of a network of sleeper agents across the U.S, activated in extreme circumstances, and given absolute authority. But it is also a link to contemporary politics that the game seems proud of, mentioning the directive by name multiple times, as well as the bioterrorism outbreak simulation Dark Winter. It’s all part of an attempt at “authenticity” and “realism” that seems to motivate the game’s depiction of a post-viral New York City.

Directive 51 is also a highly controversial document. Accused of allowing the president to take dictatorial control in the event of a disaster or terrorist attack, it was both riffed on by conspiracy theorists and criticized in the press. The fact that access to the confidential “Continuity Annexes” were denied to Congress on multiple occasions only adds to this potency. The Division, however, treats it with a strange reverence, fashioning itself as a celebration of absolute power. As a Division agent the player is portrayed as the best hope for the city, an everyday hero in a beat-up parka and jeans, ready to fight anyone who might resist. Empowered by Directive 51, they can cut through the red-tape of the judicial system and civil law, to supposedly impose order back on a lawless city through running battles and military assaults. It’s a muddled fiction to step into, one that casts you as an authoritarian enforcer with an unlimited license to kill, as well as “the savior of New York.” But when the game says New York, it isn’t referring to the citizens or the culture, instead it is referring to that most important of features in a capitalist society—property.

It’s always been a quirk of videogames that they succeed in depicting believable environments over believable people. The Division feels like the ultimate realization of this trait. The section of Manhattan island that the game takes as a setting is an artful work of digital craft. It takes a detailed one-to-one replica of the existing city as its starting point and covers it with layer after layer of enviromental detail. Every surface is creased, worn, scratched and marked, then plastered with trash, water, notes, graffiti, and greasy footprints. There is an obsession with garbage that tells the story of the breakdown of the systems of society so effectively. Bags of it lie in great drifts across roads, it fills stairways and alleys, piling up in cavernous sewers. It is an image that speaks so strongly to the supposed knife-edge the game wishes to depict society as resting on. It defines a society of endless consumption brought to its knees. When combined with the Christmas imagery that comes with the games’ “Black Friday” timescale—wrapped trees lined up on the streets, fairy lights twinkling above burnt out cars—it starts to feel like a visual interrogation of late Capitalism. And when the precisely simulated snow drifts in, and you are stalking down an empty city street surrounded by refuse, The Division seems to make sense, it seems to say something. But before long, out of the swirling flakes will come a jerky citizen, who will congratulate you for your efforts, and then ask you for a soda. And all at once, that something is lost.

The Division has a serious representation problem. Despite the complexity of its world, and its bleak sophistication, it fails miserably to represent the culture within it. Its crude depiction of a society divided entirely into “us and them” feels like the ugliest of conceits. “Citizens” are classified as those friendly-looking, passive idiots that wander up and down streets looking for a hand-out. “Enemies” include anyone who might take their own survival into their own hands. Within the first five minutes of the game you’ll gun down some guys rooting around in the bins, presumably for “looting” or carrying a firearm. Later you’ll kill some more who are occupying an electronics store and then proceed to loot the place yourself, an act made legal by the badge on your shoulder. Even the game’s “echoes,” 3D visualizations of previous events, seem designed to criminalize the populace, usually annotating them with their name and the crimes they have committed. This totalitarian atmosphere pervades everything—even down to a mission where you harvest a refugee camp for samples of virus variation, treating victims like petri dishes. Developer Ubisoft Massive runs merrily through any complexity and shades of grey in these acts, in what seems like a vain attempt to mask the fact that you are shooting citizens because they are “looters,” constantly prioritizing property and assets over human life.

When discussing these aspects of The Division it’s tempting to start linking to articles on social behavior in disasters, on the myth of widespread looting or the psychology behind it. But as interesting as these debates might be, in this case they don’t apply. While I wonder where these factors were in the developer’s supposedly painstaking research, it’s important not to confuse real-world ethics with those of a game, where a closed system functions in highly defined ways. The gang members you kill and the civilians you save in the game are not citizens, or even equals, they are simply actors within a limited simulation. What they are, though, is a representation, an image of the world we live in, reflected back to us. For this reason, like any system of representation, the game has specific politics. It doesn’t matter that the game’s associate creative director Julian Gerighty claimed “there’s no particularly political message” in an interview with Kill Screen’s Michelle Ehrhardt. What matters is that by its very nature The Division is political, and, more importantly, that those politics paint a paranoid and misanthropic image of society.

Let’s try a simple thought experiment. Imagine we modded the game to switch the character models of the idle and sick civilians with those of the hooded “Rioters.” All across The Division‘s ailing New York, men in hoods and bandanas would be stumbling along the street, asking you for food or aid, while gunfights erupted between pea-coated men and women with carefully wrapped scarves. The strangeness of this image only serves to evidence that we constitute society through visual cues, class hierarchies, and pre-formed assumptions. These assumptions are used within The Division in order to criminalise a whole segment of society. The enemies of The Division aren’t an invading army, they weren’t created by the disaster, instead, as the game suggests, they were already there. They were, says The Division, part of a vast underclass that lies at the dark heart of the city, ready to prey on the weak, waiting for their moment to rise. The Division’s viral outbreak is imagined as exactly this moment, where all the rules are forgotten and the vicious may overpower the innocent.

This is the paranoid fantasy of the right-wing brought into disturbing actualization by The Division. Look at the three gangs that form the main antagonists of the game: The “Rikers” are the prisoners of Rikers island prison that lies off the coast of The Bronx. They are the most obvious member of what The Division presents as societies’ dangerous underclass—known criminals. The “Cleaners” are former sanitation workers, who have decided that the solution to the virus is to burn it out of the city. A gang of blue-collar garbage men and janitors equipped with flamethrowers, they represent the lowest rung of the working class. The third gang are the “Rioters,” a majority black, generic street gang, decked in hoodies and caps that spend their time looting electronics stores and dead bodies. Perhaps the laziest and most repugnant of all the game’s representations, the Rioters might have been clipped from the one-sided and inaccurate media coverage of disasters like Hurricane Katrina. Their collective name even seeks to mark anybody who resists the dominant regime for execution. Together, these gangs present a trinity of soft political targets, those that can be killed with little social guilt or questioning. The Division mercilessly uses these skewed representations to justify its political violence.

It’s a perverse idea of society, one where the government and its agents are the only thing standing between the average man and a host of violent sociopaths that surround him; from the “hoods” hanging on his street corner to the janitor at his office. They want what he has, the man thinks, because it is what they lack. They want to take what he has earned—to destroy what he has built. It comes from a deep seated place of ignorance and selfishness, one that doesn’t seek to understand the world but to divide it up into property and power. This ideology is nothing short of poisonous and yet The Division uses it as the fuel for its world. It borrows, word-for-word, the rhetoric of the New Orleans police department command who after Hurricane Katrina gave the order to “take the city back” and “shoot looters.” It presents those disenfranchised by society as its greatest enemies. It follows neo-liberal dogma so blindly that in one bizarre mission it actually sends the player to turn the adverts of Times Square back on, as if those airbrushed faces and glimmering products were the true heart of New York City, shining down like angels on the bodies of the dead among the trash.

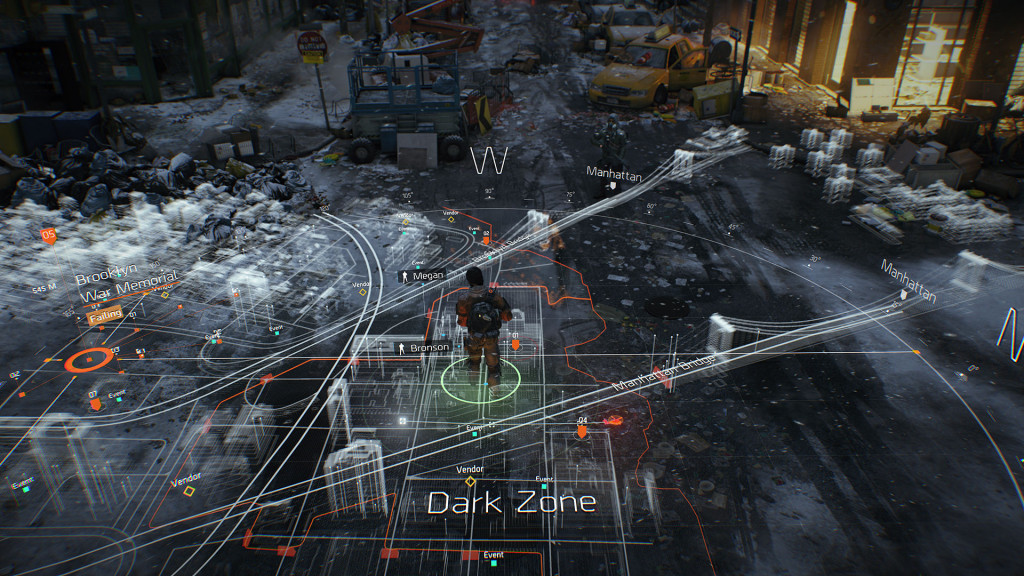

Let’s be clear here. I couldn’t care less about legislating the morality of digital characters, or attacking the prevalence of killing as a mechanic in games. What I do care about is any cultural object which sells itself on paranoia and ignorance, which propagates the worst self-destructive fantasies of Western society and that wields political ideologies under the pretence of entertainment. The Division does exactly this, its representations reinforcing the fractures of contemporary society. It’s this overriding ideology of The Division that I find hard to ignore. Even while I am cycling through its rewarding, if rote, selection of upgrades and improvements. Even while I am cutting through the player vs. player “Dark Zone,” one eye on the corners for the signs of rogue players. It’s an ideology that many will let slip into the background, as they spend hours churning through the upgrade tree, following the endgame pattern of daily missions and loot runs. It’ll still be there later in the year, as the three expansions for the game arrive, bringing with them new players and new systems. It will persist, like a virus, beneath all the firefights and the exploration, between the safe houses and the dirty, dangerous streets. It’s even there in the title, which for me no longer refers to a military designation, but the “division” between “us and them,” “the have and the have nots,” to the game’s own politics of segregation and repression. The Division is a game so eager to criminalize the poor, so eager to play into clichés of class war. Yet it staunchly refuses to take responsibility for its representations, for its politics. If we want that to change, we have to make it, and its creators, responsible.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.