“A man chooses. A slave obeys,” Andrew Ryan said. If only it were that fucking simple.

When my uncle committed suicide several years ago, I’d never played BioShock. I’d never set foot in Rapture. I’d never encountered a Splicer, nor a Big Daddy, and I’d never heard of Andrew Ryan.

I didn’t handle my uncle’s passing very well. It happened on May 12, 2008. I was sitting an entrance exam which, if passed, would grant me a full-time university place the following academic year at Strathclyde University in Glasgow. Exams were never my forte, but after a nervy start—where two of the four pens I came equipped with suddenly ran dry—I settled in and found my stride. I left the exam hall pretty confident, all things considered, got into my car and drove home to my parents’ house.

As I made my way up the path, I began texting my girlfriend to tell her the exam had went well, and that I might finally get that PS3 I’d been threatening to purchase. I put my key in the lock, gave way to my parents’ black cat who had joined me on the porch, and opened the door. As I walked into the hallway I could hear my mother upstairs laughing, presumably on the phone with someone. I glanced up from my text, and was met by my father, wide-eyed and bloodshot, and suddenly realised my mother wasn’t laughing. My dad grabbed my arm—which was in itself unsettling, as he’d never used such force with me in the past—and ushered me from the hall into the living room, before gently closing the door. “Your uncle hanged himself today,” he said. I staggered backwards, almost falling, and thinking mostly about my dad’s decision to use the word “hanged” instead of “hung,” as if his discerning grammar paid some sort of deference to the enormity of the situation.

It was easier to focus on something like that. My uncle had been developing property in Edinburgh in the years leading to his death, and had gotten himself into some financial bother. He, along with my aunt, had most recently bought a block of four flats in Edinburgh’s prestigious Portobello area, but, unable to sell three of the finished homes due to an increasingly stagnating market, he struggled to raise the cash needed to begin work on the fourth. Unbeknownst to anyone else, he was in serious debt.

His work, though, had been remarkable. The top-floor flat was furnished with the sort of decor you’d expect from a Spanish villa: spacious and streamlined rooms with real wooden floors and immaculate white walls, split by shards of light which beamed through each room’s huge sloping windows; my uncle took pride in his work, and it showed. But the ground floor flat was a building site. It was a shell, stripped totally bare, complete with tall ceilings and high wooden rafters. It was here my uncle took his life, becoming an unfortunate, yet somewhat quintessential, victim of the global financial crisis.

Shortly after my uncle’s funeral I got around to buying that PS3 and, with it, the original BioShock. The months that followed were like nothing I’d experienced before. I harboured some warped machismo doctrine that those who admitted being depressed were weak. My mother began counseling. There had been some dispute with her boss prior to my uncle’s death which had led to her taking some time off, but this was the tipping point that forced her into early retirement. Every now and then my dad would ask me if I was doing ok. I’d always say yes. And to be honest, I thought I was. After all, depression wasn’t real, right? And there were a lot of people much worse off than me. At first I hadn’t noticed my mood changing. I didn’t feel the resentment, or displaced anger, or even an inordinate amount of the sadness associated with loss—but I suddenly stopped enjoying things. Holidays, nights out, music festivals all came and went with little notice. I passed the exam and got accepted into Strathclyde. I deferred entry to the following year.

“Is a man not entitled to the sweat of his brow?” asked Rapture founder Andrew Ryan. Taken on its own, it was a fair enough question. But when bound by the context of his inherently imperialistic view of Rapture; accentuated by the elitist tenets central to his imagining of a utopia—it was for me a hard question to swallow.

Suddenly Ryan’s words somehow resonated with my situation; with my uncle’s death. “A man chooses. A slave obeys,” he said, as if championing this idealistic axiom in any way justified the ideal itself. My uncle worked immensely hard to earn a living, took immense pride in his work, and yet struggled to “earn” the sweat of his brow. “What is the difference between a parasite and a man? A man builds.” But I couldn’t categorize my uncle so neatly as either. His work ethic fit Ryan’s definition of a man, yet suicide marked his only means of escape. Man or slave? Sure, suicide is a choice; but if governed by extreme emotion, it can also be a means of escape. My uncle’s suicide was his journey to Rapture, his escape from reality, and I viewed its capitalist, all-consuming allure akin to the devastating affect the desire for money, and latterly avoiding debt, had incurred on my uncle. Yes, a man is entitled to the sweat of his brow, but at what cost?

So I in turn spent hours plundering Rapture, not as a break from Ryan’s perceived societal mediocrity, but as a means of offloading my discontent. No splicer was safe as I stormed the desolate corridors and grandiose ballrooms of the underwater dystopia. I took immense joy in gunning them down, setting them alight, or, even better, savagely bashing them to death with my drop-forged wrench. I reveled in the tedium of the search-and-retrieve quests as I scoured every nook and cranny for fresh blood. Big Daddies presented a challenge, and constant Vita Chamber shuttle runs became less shameful with each bout. I didn’t give a shit how it was orchestrated, just as long as they wound up dead. And every single Little Sister got harvested.

Fuck you, Peach Wilkins. Fuck you, Sander Cohen. And fuck you, Andrew Ryan.

Instead of starting university in 2009, I travelled to Australia, where I spent two years living with my girlfriend. In so doing I left behind something I couldn’t really explain, but something I knew I needed to get as far away from as possible. Time passed, as did the unwelcome feelings; they seemed almost forgotten. I returned home in 2011; BioShock 2, at some point in the interim, had been released. While away, my depression had seemed lifted, but when I got back I realized it had just been put on hold. Rapture was the same. Glasgow was the same. I was the same. And so resumed a very unfortunate, very familiar cycle.

But something in this return to Rapture helped me identify my problems—a rare pleasant example of familiarity breeding contempt—and it was only after racing Eleanor Lamb to the surface as Rapture crumbled around us at the climax of BioShock 2 that I decided to open up to my family and tackle how I was feeling head on, something I had never considered before. Up until that point depression wasn’t real, or even if it was—I certainly didn’t suffer from it. Scottish people, particularly Scottish men, tend to suffer from a self-effacing inferiority complex, wherein talking about your emotions or how you’re feeling is perceived as a sign of weakness, whatever that even means. This is by no means exclusive to Scotland, but to put things into perspective: in 2012, the suicide rates of Scottish men were 73% greater than of those in Wales and England. No matter how cliched it may sound: a problem shared is a problem halved.

Rapture no longer haunts me. I got the help I needed, or at least am getting it. While playing BioShock Infinite last year, I had a moment of epiphany when I was suddenly back in Rapture at the game’s end. I felt a quick surge of panic, followed by—nothing. I was in Rapture the way other players had experienced it. In a way, it was my first time there.

No one expects depression, and in many situations it’s hard to identify. There will always be a man, or a woman. There will always be a city. I can’t say whether or not there’ll always be a lighthouse. But there certainly will always be someone to talk to. Do it.

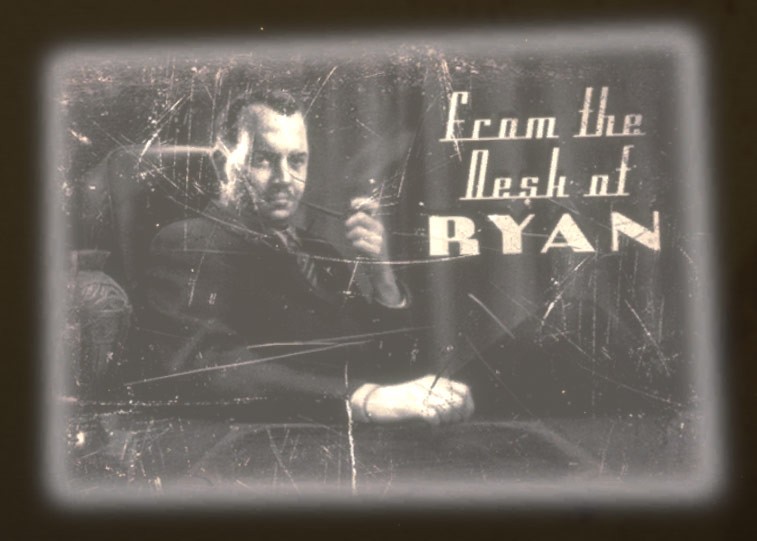

Header image via Eric Stafford