History, in case you were wondering, covers a good chunk of time. Much of that time has been horrible, but there’s plenty of it. How, then, does one go about representing history? Should the focus be on the time or the suffering?

The normal solution to this problem, as is evidenced by the history section of any bookstore, is to focus on suffering over time. The thousands of World War II books may feel like they take years to read, but they are each about 500 pages long. They are indexes of suffering. Timebound, which is being announced on “Back to the Future Day,” aims to reverse that trend and put the emphasis on time.

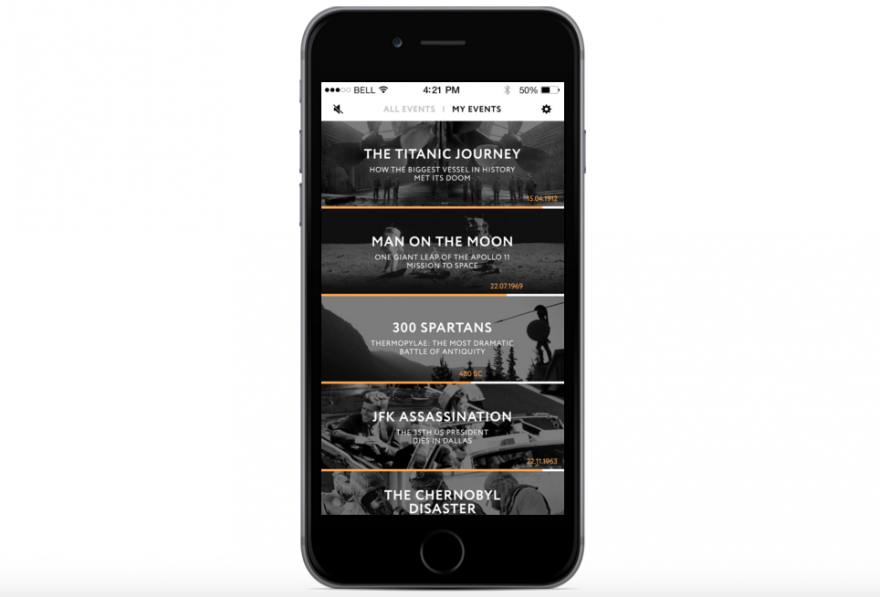

The game, which was developed by Mika Golubovsky and what he describes in an email to Kill Screen as “a team of writers, designers and developers with experience in media and academic history,” provides push notifications for historical events spaced out at verisimilar intervals. The events that will come with the initial release apparently range from a couple days to a couple years, though Golubovsky writes, “We’re even thinking about the Hundred Years’ War, so people have a chance to share the experience with their grandkids.”

This raises a few questions, which point to both the potential challenges inherent in this concept and its appeal.

First, how long does a phone last? The average smartphone has a lifespan in the region of three years, which means that it’s not clear what you’d be handing down to your grandkids. Or, to use a more charitable example, the odds of your phone outlasting a real-time rendition of World War II are not favourable. This is an interesting reflection on physical and digital mortality, though it is probably not the point Timebound is trying to make. The app is, in a sense, trying to make history tangible, but for events longer than a few months, it is actually likely to produce another piece of digital ephemera—a login you carry from phone-to-phone, assuming you don’t forget it. You can carry history with you, but it’s easier to shake than the real thing.

The question, then, becomes how often your phone buzzes? Here’s how Golubovsky explains it:

Once you’ve picked an event, you get push-notifications about its every twist and turn. You live through the event, hour by hour. So if you picked World War Two, you’ll be living in it for six years, receiving all the significant information at the exact time of day it had actually happened.

So there’s your answer: possibly every hour. Which, I don’t know? Why not every few minutes? It’s hard to argue that significant events do not sometimes follow one another in rapid succession. And maybe Timebound really will go there. The sinking of the Titanic, which is one of the events set to be included in the beta version, could conceivably work in this timeframe.

One other question: What might Timebound do when nothing of note was happening? Borrowing Golubovsky’s Hundred Years War, what might be made of the relative peacetimes of 1360-69 and 1389-1415? Would your phone go silent for nine and 16 years, respectively? Would you wake up one morning, now lacking the follicular endowment of the last time Timebound served you a notification, and suddenly discover that hostilities had resumed under Henry V? This is both a fascinating prospect and a somewhat impractical idea: The ideal interval between notifications is probably not longer than it takes to conceive, gestate and raise a child up to their Bar Mitzvah. This, incidentally, is probably why Golubovsky notes that the Hundred Years War is an idea for down the line and not right now. The sinking of the Titanic has far more practical pacing—unless you’re James Cameron, that is.

Might this all be a bit much? That is the ultimate luxury of exposing yourself to history ex post facto: You can set your own terms of engagement. So maybe a minute-by-minute wouldn’t be historiographically excessive, but it would probably constitute a poor user experience. (Note that this is not what Timebound proposes; it is simply the fullest extension of its premise.) Which, again, fair enough. It’s not like World War II had a good user experience. The great irony of Timebound is that a part of the project exists in the past but its questions about the curation and frequency of push notifications is very much of the present. Timebound purports to be a real-time rendition of history but there are subjective judgments—technological, historical, and otherwise—embedded in this recreation.

There’s nothing wrong with that. A certain amount of subjectivity is inherent on all historical undertakings. Most such undertakings, however, do not present themselves as real-time renderings. The compression of time makes the inherent judgments more apparent: obviously things had to be culled a bit to fit a book. Timebound, like the many niche historical Twitter accounts that tweet out events, are in comparatively uncharted territory. There are just as many judgment calls to be made here, but our understanding of what the form entails lags behind.

You can find out more about Timebound on its website.