A new standard has been set for children’s apps

“Do you have kids?” asks Tinybop Founder and CEO Raul Gutierrez. We’re discussing The Human Body, the first act in his company’s The Explorer’s Library series, and, despite being the interviewee, he’s asked the first question. “Kids play with apps differently,” he explains, “so I always ask that first.”

This obsession with the unique ways that children experience the world is at the heart of Tinybop’s work. They make digital toys: apps that attempt to broaden kids’ horizons while speaking in their language. The Human Body is available in 59 languages but communicates through wordless interaction. This is the language of the iPhone and, Gutierrez tells me, it is also the language of children.

“I have two kids and they are first generation to grow up with touch screens,” he explains. “They’re not just phones, or game consoles, they’re also cameras, sketchpads, and music makers. Sometimes they’re friends; these are tools for creative expression.”

Gutierrez was working on other mobile projects when his then-six-year-old asked if he could trade his upcoming birthday party for an iPhone. “If you know anything about kindergarteners or first graders, the birthday party is one of the most important events in their world. It’s the currency they use,” he tells me. “And that moment really made me stop and think about how important this device was to him.”

“The birthday party is one of the most important events in their world. It’s the currency they use.”

Gutierrez started downloading apps to play with his kids. The number eventually reached 200. “I felt there was this tremendous opportunity to create apps as good as the best science books and models I had loved as a kid, but exactly right for this new context that is so sticky and appealing for kids.”

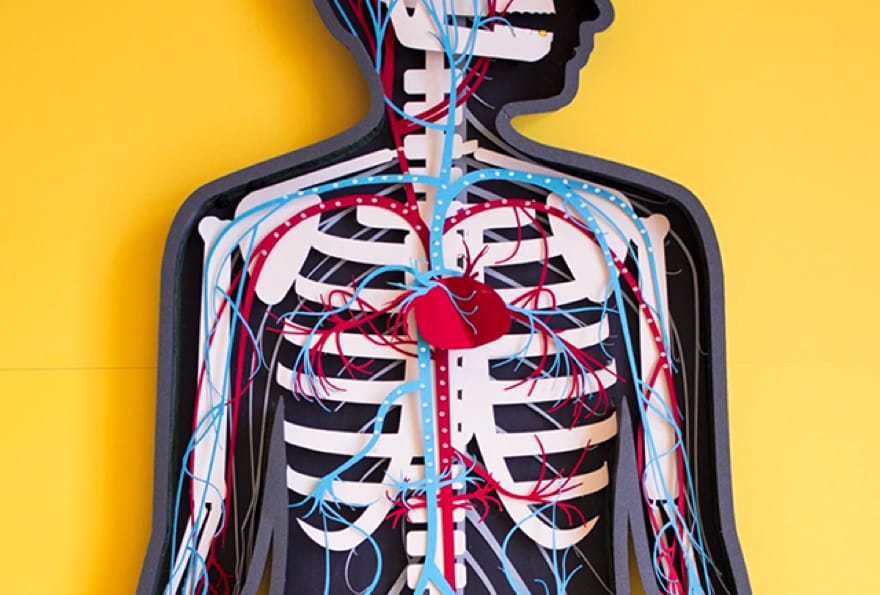

These books and toys, particularly the transparencies found in dictionaries, are Gutierrez’s most common points of reference as we discuss the Explorer’s Library, but there’s nothing retro about it. The Human Body doesn’t feel transposed from another era; it highlights the native, unique abilities of mobile devices.

The Human Body, like this human’s body, reacts to stimuli. It’s a giant exercise in cause-and-effect. Dragging an air bubble up its animated oesophagus, for instance, produces a satisfyingly resonant burp.

“It’s like the world’s most elaborate burp and fart app,” Gutierrez says.

That isn’t a joke, or even an inaccurate statement. The Human Body’s bodily functions are rendered in all of their squishy, fetid, sonorous glory. Each fart and belch is as unique as a snowflake. An enterprising child could play The Human Body’s intestinal tract like a musical instrument—heaven only knows that I tried.

“When a kid is pushing a bubble of air up the esophagus and it’s burping, we’re looking at the acceleration of how fast the kid is pushing the burp out of there and we’re modifying the pitch based on that acceleration a little bit so you don’t hear the same sound over and over again,” says Gutierrez.

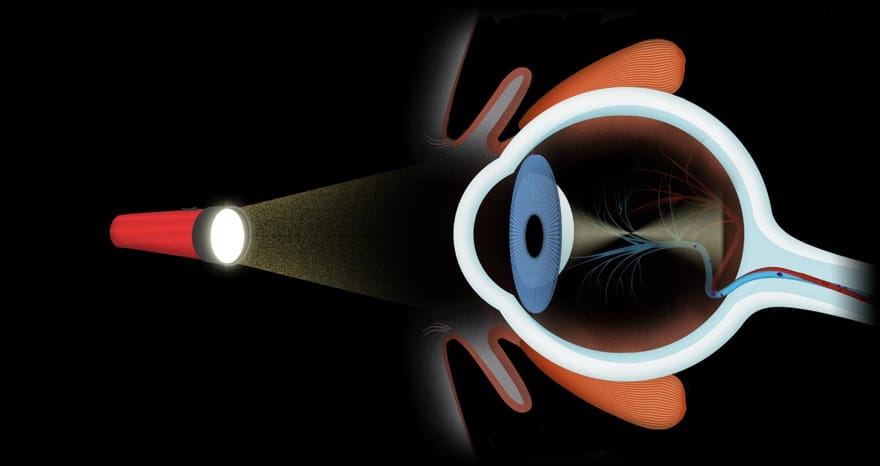

For the less scatological, this sensibility extends to the rest of The Human Body. Instead of telling kids that their eyes process images by flipping them, The Human Body flips the image from your front-facing camera in real time. Like the burps, this experience is subtly different each time you pick the app up.

“One of our guiding principles is animating with physics versus repetitive sprites,” Gutierrez explains. “We change the nature of the animation, based on the physics of the simulation and that seems to add stickiness.”

These interactions are tested on a range of children. Gutierrez’s children remain go-to guinea pigs. Tinybop also conducts play testing at schools and in their Brooklyn office, which is conveniently located above a social services organization and karate studio, where further feedback is easily sourced.

“We try to watch them very closely and see where they get frustrated, where they get bored,” Gutierrez says. “We focus on solving those pain points to keep kids engaged.”

This careful focus to children’s’ perspectives makes it hard for an adult to know what to make of The Human Body. Its visuals are engrossing but its interactions can be opaque. I sometimes tapped at the screen, haphazardly searching for interactions. Usually they appeared and were excellent. Sometimes I swiped into the void. Does this experience mean anything if the app is clearly not for me?

“Many parents are confounded by our apps,” Gutierrez tells me, “then they give them to their kids and say, ‘My kid was playing with that app for hours. What’s going on?’”

This phenomenon is even more common with Plants, Tinybop’s follow-up to The Human Body. “You’re changing the seasons, you’re moving animals around, you’re making rain, or sparking wildfires,” Gutierrez explains. “There’s not a lot that’s obvious to do in the adult gaming sense.”

Tinybop’s body of work is appealing precisely because it has a specific idea of what it is and who it’s for. The “loves” page on their website includes videos by Charles and Ray Eames, Prokofiev’s Peter and the Wolf narrated by Sean Connery, and Kentucky Route Zero. This mood board isn’t just pabulum. The Human Body has a distinct visual sensibility: it renders food as emoji and the body as a mix between a cartoon and polygonal art. This is not lowest-common-denominator “art for everyone,” which, paradoxically, is why it’s hard to imagine anyone disliking it.

In that respect, Tinybop balances the specific and universal. “We always try to create gender-neutral apps,” Gutierrez explains. “The Human Body is now in 59 languages, and sells in every app store in the world, so when we hit that button, we’re selling everywhere. We have to be conscious of cross-cultural concerns as well.”

This balance extends to the narratives Tinybop weaves. Homes, the latest act in the Explorer’s Library, is inspired by James Mollison’s Where Children Sleep. Its subject, Gutierrez says, is “The things all kids do, like eating, sleeping, going to the bathroom.” Yet, he continues, the message of Homes is: “All those things look very different in different cultures.”

“By the end of The Explorer’s Library, we’ll have a really nice package of apps that cover the big universal topics in science that kids everywhere need to know about,” Gutierrez says. Playing with The Human Body as an adult, you can envision that future and desire those digital toys, which are like nothing you’ve ever owned. But Tinybop’s toys are not for you, and that’s how you know they’re on to something.