“As children of the 80s,” starts game creator Mike Boxleiter, “we remember what life was like before terrorism came to this country.” Despite having sent this sentence to me by email I can tell that Mike wore his best poker face when typing it. He’s talking a sham. When he describes his longing for simpler times, before we found out that “anybody could be a terrorist and you wouldn’t even know it,” I’m fully aware of what he’s doing. It’s not hard to spot.

Mike is channeling the hysterics of an American who has taken the mass media’s message to heart. It’s a paranoia born of Bush-era politics and the post-9/11 “War on Terror,” which saw news anchors singing loose-lipped about conspiracies and inside jobs. First, the terrorists were far away, in the Middle East, but then they were your next-door neighbor, your boss, your mom, your pet dog.

“The guys who run your local bodega could be plotting to sneak arsenic laden pizzas onto a military base,” Mike continues, making his farce clear by running it through pure absurdity. “Your accountant might be dusting the inside of vending machines with anthrax, and your own grandmother could be organizing a raid on the Byron Nuclear Generating Station, hoping to steal enough Plutonium-238 to set off a dirty bomb at the heart of downtown Chicago!”

The reason for Mike’s travesty is to proffer the thinking that drives the modern-day fiction of his new iOS “puzzle-game-with-a-purpose” TouchTone. He’s teamed back up with Greg Wohlwend for the occasion, with who he previously hacked together the shot-matching basketball mobile game Gasketball.

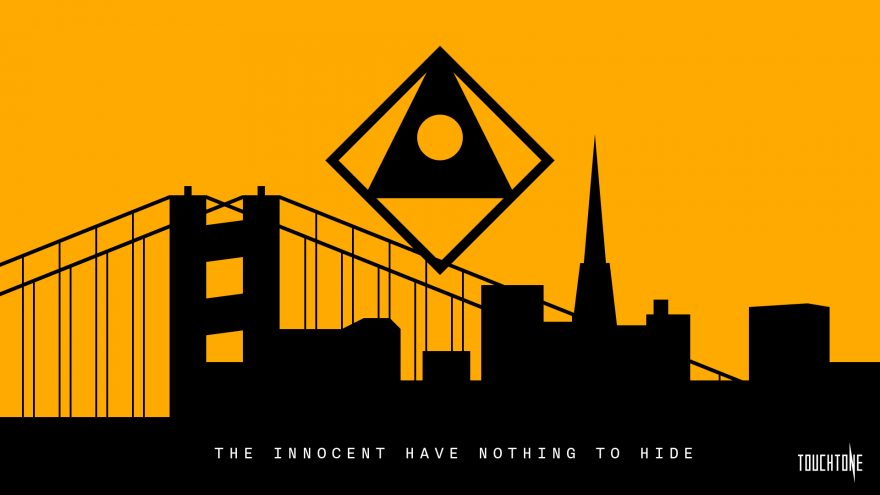

The puzzles in TouchTone have you bouncing lasers around a grid into receivers, establishing a connection—what the pair describe as “a cross between Rubix cube and Khet (think laser chess).” Making enough of these connections gives you access to citizens’ texts, emails, and phone calls. But you are not a spy. This is an alternate reality (which, worryingly, isn’t all that alternate at all) in which a fictional government organization has turned to crowd-sourcing its perennial battle against terrorists. It’s the consequence of basing an anti-terrorist policy on the mantra “the innocent have nothing to hide.”

As such, once you’ve read through the other person’s private communications that you unlocked, you then have a decision to make. Is any of what you read pertinent to the government’s interest in finding traitors to the state? More simply: do you suspect this person is a terrorist?

Mike and Greg think that TouchTone is important. Even though it’s expressed through a fiction, this is a game specifically about the reality we’re living in, right now. It couldn’t be any more relevant. “What once started as a simple game jam prototype has evolved into a platform for our outrage at the erosion of privacy in this post-Snowden era,” Greg said.

This outrage is subdued. In fact, it may not even be present in TouchTone at all. For it’s not a means for the pair to splutter in angered tones about their disbelief at the state of society, as if it were a digital soapbox. Instead, TouchTone has you arrive at this conclusion by yourself. At the start, I found myself disagreeing with what the game deemed potential terrorism a lot, which embedded the idea that the system was wrong, as if it wasn’t sufficient for its purpose. I’d say what changed later on in the game but, well, that would be spoiling, but it does continue to explore its theme to a similar effect.

Obviously, there’s a lot riding on the player seeing through the game’s fiction, to understand the implicit message at its core, and to not find agreement with its superficial layer. For this reason, during our conversation, Greg mentions that he’s “a bit nervous” about TouchTone. It’s not like the previous games he has worked on. Which, by the way, include Ridiculous Fishing and Threes!; two highly successful iOS titles. Why should he be nervous?

In Greg’s words, TouchTone is “a lot to bite off for iOS—a marketplace traditionally hostile to politically-themed games.” Indeed, Apple is known for rejecting games that might be considered offensive due to depicting real-life people or touching on political themes. Obviously, this shuts down any attempt at satire or parody on its App Store. So, TouchTone ran the risk of being rejected by Apple. Which may lead you to wonder why Greg and Mike were intent on funneling their message through an iOS game in the first place. I did, and so I asked Mike why he felt this was the right format. He brought back his ventriloquism act but ended up making a good argument:

“While a book might empower thousands to help suss out threats to national security, only a game can aid in that task in the most direct way possible. These dangerous texts, emails and phone calls all happen on these devices in our pockets, what better place to confront them than on that same battlefield?”

It’s these devices that are responsible for empowering us all. We have the reporter’s equivalent of a Swiss Army knife in our pockets at all times: there’s a camera for taking pictures, a microphone for recording speech, and immediate internet access to spread the information. With these we are able to manufacture a conspiracy as we see it, and spread it to hundreds and thousands of people, should it go viral.

“If you solve something, say something,” goes one of TouchTone‘s lines of advice. It’s obviously referring to the game’s puzzles, but it’s also the attitude that seems to fuel a lot of citizen-led investigations. With this on loop in their minds, these people effectively justify themselves breaching a company’s or person’s privacy. It’s all for the greater good, right? TouchTone confronts us with this reality and asks us to question it, to interrogate ourselves, to take a long hard look in the mirror. What’s the real threat here?