One of the core tenets of horror is a sense of powerlessness. The audience goes into the genre knowing full well that, in order to get something from the experience, they have to submit themselves to things explicitly designed to scare them. Sacrificing our control is what makes the creeping suspense and outright fear of a well-made horror movie or book work. We allow ourselves to be played with because we want to be scared.

Videogames complicate this because they’re a medium that’s meant to present players with control over their experience. Horror games can do a great job presenting frightening ideas through sound, visuals, and story, but they’re often hamstrung by the fact that, by their very nature, they allow the player the minimal safety net of agency. If something frightening runs across the screen, the protagonist can respond with the press of a button, running, hiding, or readying a weapon. If something too horrible to look at is occurring on screen, the camera can be swung away.

Supermassive Games’ Until Dawn understands that this is a problem unique to games and attempts to solve it by stripping the player of the sort of direct control they’ve come to expect. At first glance, the developer’s solution seems to be rendering the experience in the form of a slick, computer generated interactive movie. Until Dawn’s opening chapter—a brisk, effective introduction to a group of teenagers whose bullying of a friend leads to a traumatic accident—offers little control over its playable character. She is capable only of walking around a kitchen, picking up interesting objects, and looking at them. When she flees the lodge the friends are staying in, chasing another character out into the snow of the isolated Alberta mountains, only timed button prompts are shown on screen as indicators that the audience can influence the outcome of what they’re watching.

It’s when the plot picks up again, flash-forwarding to the one year anniversary of the prologue’s events and the cast’s return to the site of the accident, that Until Dawn’s main systems are fully introduced. The most important of them is its Choose Your Own Adventure-style approach to character development. When it’s time to make a decision—which range from something as innocuous as whether or not to read an incoming text on someone else’s phone to life-or-death decisions like running or hiding from a pursuer—the player gets to pick how to respond. The game, shifting between the perspectives of its cast, encourages an illusion of ownership over the story and the characters. Unlike the straightforward opening, the rest of Until Dawn is concerned with constantly reminding the audience that how they guide the cast will have an influence on the story’s outcome.

This is true, but never to the degree that the game suggests. The characters may relate differently to one another—even live or die—based on the player’s choices, but the game is still an authored experience. It alters itself in smaller ways without ever stopping its inexorable march toward the same general conclusion. All the same, Until Dawn is better for calling attention to its branching narrative. (It dubs its mutable system the “Butterfly Effect” and pops up notifications every time the player has performed a consequential action.) It helps to distract from the fact that players only receive direct control over a given character when they’re exploring the environment. When it comes time to actually deal with dramatic circumstances—fleeing a killer or trying to rescue a friend from certain death—control is wrenched away, reduced to nothing but timed button-presses. This is the opposite of what videogames normally offer. Until Dawn’s action scenes turn the audience into spectators, only capable of directing the broad strokes of what’s occurring on screen. Rather than irritate, though, the powerlessness of these snap decisions combines with the constant “Butterfly Effect” reminders to heighten the audience’s sense of responsibility. If a character dies it becomes their fault—no matter how careful they’re being to keep everyone safe. Even though they’re never in complete control, the game’s designers suggests that the audience should feel a tinge of guilt every time something goes wrong.

This type of design wouldn’t work nearly as well if Until Dawn’s wasn’t so tonally confident. Supermassive pays homage to everything from Saw and The Descent to House on Haunted Hill, Halloween, and Night of the Demons, capably flitting from subgenre to subgenre as the story progresses and, surprisingly, maintains a coherent plot in the process. This is partially due to the great sense of place established through the visual design. Fixed camera angles allow for deliberately crafted shots. In some, the characters must navigate long corridors bathed in shadow, or move through artfully composed frames where opened windows highlight a potential source of danger. An orchestral score accentuates many of these moments, though there are just as often long stretches where nothing is heard but the howling mountaintop winds, creaking floorboards, crunching snow, and the murmuring of unseen threats. The blasts of discordant strings and spidery, high-register violins that accompany surprise scares are generic, but the atmospheric music is something far better—grand, classic-sounding pieces whose beauty is intentionally marred, like so much good horror composition, by always resolving on minor notes or cutting short a potentially cathartic crescendo. It’s music indebted to 1960s and ‘70s haunted house films—the sort of soundtrack where a sense of majesty typically underscores the grandeur of vast, crumbling mansions.

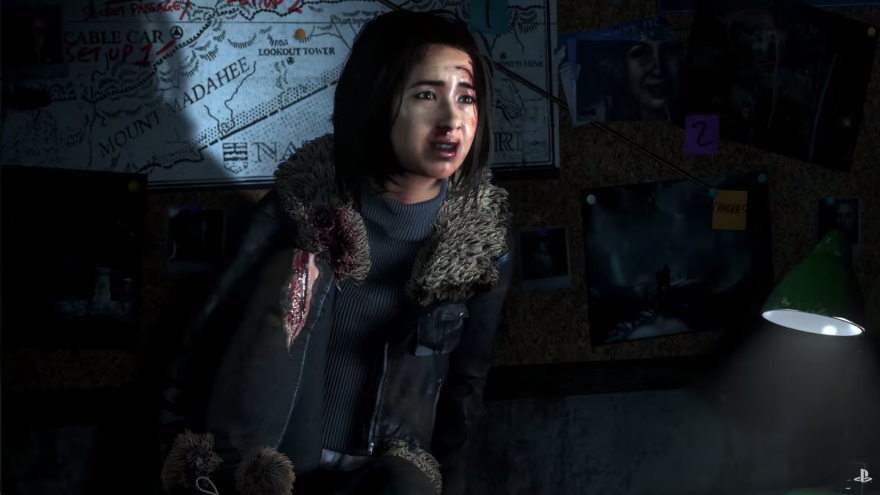

All of it lends an extra gravity to the fate of Until Dawn’s cast—an appropriately shitty group of teenagers who all look to be in their mid- to late 20s. The highlights are, of course, the biggest jerks. Worst (and best) among them are Mike, whose impeccably stubbled face seems incapable of displaying anything but sarcastic, handsome-dude smirks or hapless, hangdog concern, and Emily, who, even when facing her own death, can’t resist an opportunity to pick fights with other characters. Each of them is a teen horror caricature, but they’re all written and acted well enough to elevate the schlock above what would otherwise be tiring self-awareness. Even when Until Dawn is hammy—the most outré moments are chapter intervals featuring Peter Stormare as a scenery-chewing psychiatrist—it’s still skillfully and sincerely composed.

Where it suffers most is in its willing embrace of some of horror’s worst tendencies. A prolonged sequence forces the heroic character Sam to flee a killer dressed only in her revealing towel, a decision that brings the spectre of sexual assault into a story that otherwise avoids the subject. Cree mythology is used to enrich the game’s story on one hand while also turning sacred totem poles into silly, prophecy-enabling collectibles on the other. It also encourages the stigma that all mentally ill people are dangerous. For a title otherwise willing to reinterpret (subvert would be too strong a word) long-running horror crutches, shaping them to fit the purposes of its own story, Until Dawn stumbles by not questioning the worth of these conventions. It’s a rare example of the developer failing to consider the nuances of its own storytelling.

Until Dawn is a game constructed by people who understand how to manipulate its players’ sense of control. It’s informed by a deep study of horror films and smart in its consideration of how to employ this understanding in an interactive medium. It only fails in its uncharacteristic acceptance of a few outmoded tropes. In some ways that enhances Until Dawn as an attempt to properly translate its genre to a new form, while keeping its spirit intact. In others, it’s a disappointingly familiar problem to find in a game with so many novel ideas.