On February 16, 2014, a local artist named Maximo Caminero walked into Miami’s Pérez Art Museum a nobody and exited, in handcuffs, with his name lighting up major media outlets worldwide. He achieved this feat by intentionally shattering a sculpture included in the celebrated Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s retrospective exhibition—an urn from the Han dynasty that Ai had covered in a coat of boldly colored industrial paint. The work was meant to provoke, especially within Ai’s home country … but he likely never anticipated that its harshest reaction would come from a Dominican-born painter living in the U.S.

The incident unleashed a Biblical flood of press, from mainstream news platforms to niche art-world media. Some focused on the culprit’s leaky justification: a protest against the museum’s focus on international artists instead of local ones; others spotlighted a 1995 work of Ai’s called Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn—a trio of photographs depicting the artist doing exactly what the title indicates—in order to frame his disapproval of Caminero’s act as hypocrisy.

But as Ben Mauk pointed out on The New Yorker’s Currency blog, there was one overwhelming commonality between all these stories: Almost every headline touted the alleged value of the destroyed artwork. Instantly and eternally, the object became known as Ai Weiwei’s “million-dollar vase.” Despite the wide range of opinions about Caminero’s crime and its takeaways, this aspect, at least, everyone seemed able to agree on.

A few days later, hacker/programmer/self-proclaimed information artist Grayson Earle launched an online game adapted from the incident. Ai Weiwei Whoops! was born, to paraphrase its “about” page, in order to interrogate Walter Benjamin’s concept of “aura,” or the sanctity we tend to ascribe a physical artwork due to its one-of-a-kind status. However, the game’s deftest critique of the arts is both more concrete and more systemic than any aesthetic conceit—and, unlike its real-life inspiration, may be a happy accident.

///

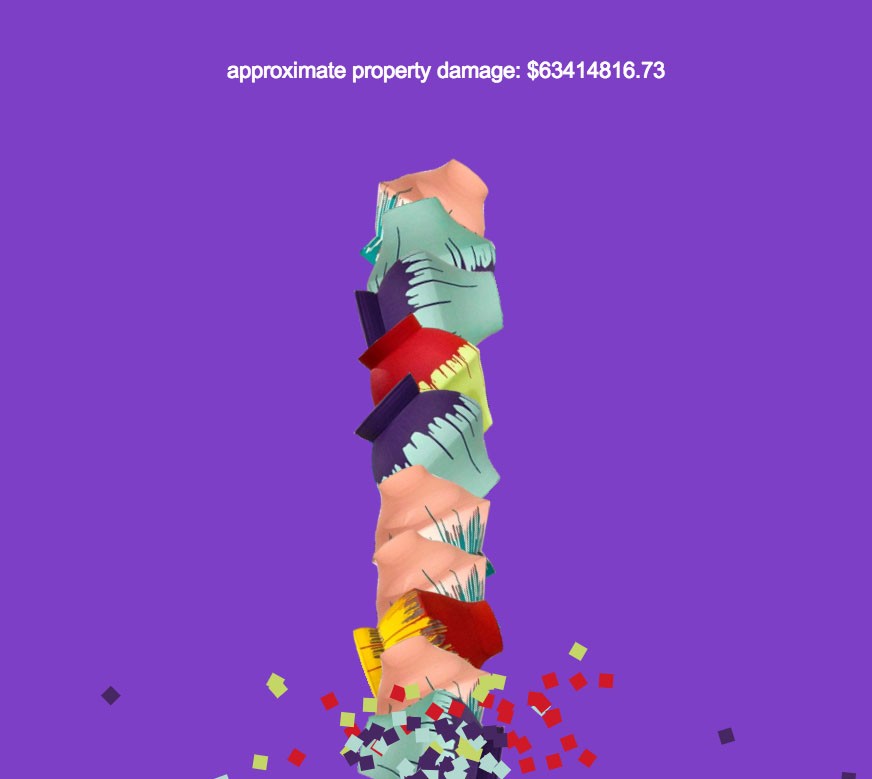

Ai Weiwei Whoops! offers no instructions, yet the devilish objective would be clear even without knowledge of the debacle at the Pérez. The moment the player drags her cursor onto the purple void of the game’s browser window/playing surface, it’s replaced by a rough image of one of Ai’s repainted Han dynasty urns—a digital stand-in for the piece that Caminero destroyed. From there, all the player needs to know is provided by the page’s tantalizing header: “approximate property damage: $0.00.”

The first time I played, I swooped the urn around the void for probably thirty seconds, testing for any other wrinkles that might reveal themselves before I caved to the obvious. None did. So I clicked my track pad, and the urn I’d been controlling immediately dropped into a gentle but irreversible free fall, at about the same casual velocity as an oxygen-filled balloon. Another urn in a different colorway immediately took its place as my cursor. When the plummeting sculpture reached the bottom of the browser window a beat later, a musical shatter sounded out; the urn exploded into a shower of colored pixels; and a nearly million-dollar figure replaced the triple zeros in the “property damage” header. The game was on.

I continued demolishing pottery, but with an eye toward unearthing whatever additional opportunities Earle had undoubtedly built into the game. I tried dropped urns from a variety of different heights; I tried to see if I could combo the damage fighting game-style by smashing multiple urns into the ground at about the same time, or crushing one into the exploded debris of another; I even tried pausing my violence to see if I would be penalized for it.

None of these choices changed anything. I discovered that each smashed urn produced a slightly different property damage valuation—always between $900,000.00 and $1.1M—but that figure bore no causal relationship to my technique; the numbers seemed to be generated at random. The altitude of the drop didn’t matter. I couldn’t combo the damage. And if I stopped vandalizing, even for an extended period of time, all that happened was that the “debris” from my previous violence gradually disappeared. Not exactly a heart-racing development.

If the game didn’t reward nuance, fine. I would give it a crime wave. I positioned my latest urn as low to the bottom of the browser window as possible and began clicking furiously, initiating enough wanton destruction that the sound effects couldn’t keep up with the breakage. I continued my berserker rage for about fifteen seconds, then looked up at the property damage counter to check my progress.

If the game didn’t reward nuance, fine. I would give it a crime wave. I positioned my latest urn as low to the bottom of the browser window as possible and began clicking furiously, initiating enough wanton destruction that the sound effects couldn’t keep up with the breakage. I continued my berserker rage for about fifteen seconds, then looked up at the property damage counter to check my progress.

I thought reaching some set dollar value might be the key. $100M seemed a likely target. What would emerge when I crossed that barrier—a bonus? A badge? A level up? I soon cracked it, and what happened was this: absolutely nothing.

Thinking I may not have gone sufficiently ballistic, I continued shattering urns. I crossed $200M, then $250M. The approximate property damage figure kept mounting as long as I kept clicking. But no new stages, rewards, or acknowledgments of any kind arrived. I felt like a child throwing a temper tantrum in an empty house.

I briefly considered trying to surpass $500M, or even a billion… then thought better of it for the sake of my track pad and my arthritic future. If Earle hadn’t built any kind of triggers into the game by this point, I doubted that anything novel would arise even if I managed to destroy enough vases to rival the GDP of Ai’s native China.

So I stopped. I squinted at the red and yellow digital urn suspended in mid-air onscreen. And I wondered … What kind of game is this?

///

Game designers have dramatically evolved the concept of what a game can be since I spent my childhood pumping tokens into a Street Fighter II machine at my local Aladdin’s Castle. But in their most basic and most traditional form, games tend to be shaped by three elements: a goal, a mechanism to achieve it, and an antagonist to complicate those efforts. The elements can appear in a number of different permutations. Kill or subdue all enemies before they do the same to you. Solve the puzzle or remain forever locked in stasis by the puzzle-maker. Score as many points as humanly possible before time expires or the available number of chances dwindles to zero.

However, removing any one of those three elements from the equation mutates the game’s entire identity. Combine an antagonist and a goal—but omit a mechanism to achieve it—and what results is an insurmountable problem. Failure becomes inevitable because the player lacks any means to counter her opponent. A more progressive player might be able to extract some philosophical or emotional value from such an experience. But to a traditionalist, it’s no longer a game if there’s no hope of “winning.”

The same could be argued for a game without an antagonist. Offer a classically minded player a goal and the means to achieve it—but remove all resistance from her path—and the end product risks being seen as, at best, practice. Like the previous scenario, the fix is still in … just on the opposite side of the ledger. The formalist player will likely feel that her “victory” is hollow because the game was rigged in her favor all along. And that makes it no game at all in her eyes.

The third leg of this analysis—removing the goal—would be considered logically impossible by a strict constructionist of gaming. From that point of view, the whole concept of a game crumbles in the absence of a clear objective. There can be no antagonist if there is nothing for the player to pursue or even maintain. And as for the mechanism to achieve the goal, how could one exist if there is no goal in the first place? It may sound like a Zen koan. To a traditionalist, though, it’s just nonsense.

///

Although Earle bills Ai Weiwei Whoops! as simply a “game,” what I realized after my failed spree was that it defies the formalist definition. He’d stripped his creation of both an antagonist and a goal. In fact, it wasn’t even fair to say that my actions had “failed” because the onscreen world offered no way to lose: no enemies trying to prevent vase breakage; no timer threatening to expire; no finite number of urns to limit my vandal urge. I couldn’t be forced out. The game only ended when I chose to quit.

What I initially interpreted as the goal in Earle’s digital arena—maximizing the property damage total—turned out to be an illusion, too. The calculator continues to multiply in lockstep with each successive shattered urn. But does this qualify as progress in any classical sense? No, because true “progress” depends on a destination. If I started to, in the words of Quentin Tarantino, walk the Earth like Kane in Kung Fu, I could quantify how far I’d physically moved from my starting point. But that’s just an odometer reading. “Progress” would mean gauging how close I was to reaching my endpoint … and that would be impossible if I had no endpoint in mind.

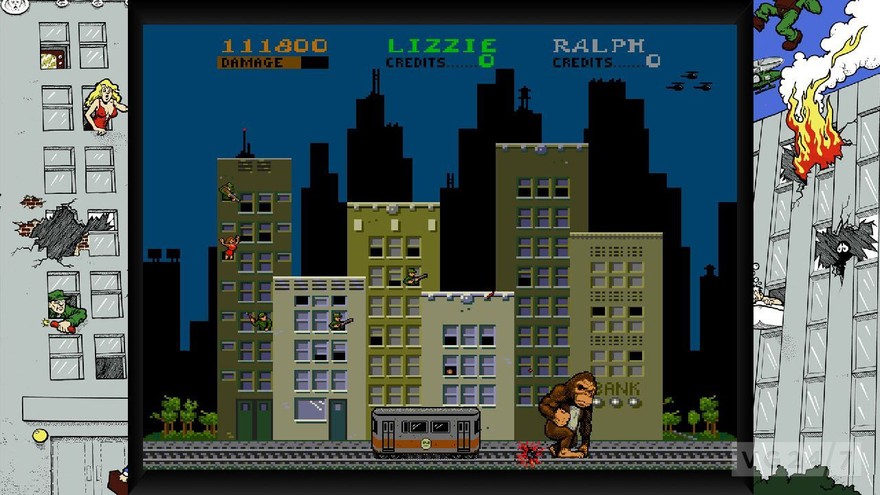

Ai Weiwei Whoops! functions on a similar plane. A player can ravage urns until her device’s battery melts, but it will never earn her anything in the context of this nontraditional interface. Compare it to a classic game like Rampage, where destruction earns points and provides the path to new stages, and the difference is stark. So stark, in fact, that to a gaming formalist Ai Weiwei Whoops! may feel like a kind of digital purgatory—a limbo state offering her no more than an opportunity to spin her wheels eternally for zero gain.

However, the defiance of traditional game standards in Ai Weiwei Whoops! ultimately leads to its greatest cultural relevance. To understand how, we must look not at Maximo Caminero’s decision to annihilate Ai’s sculpture in Miami, but at the greater ecosystem he intended to protest: the contemporary art world at large—which more than ever means the contemporary art market.

///

In his aforementioned New Yorker piece, Ben Mauk goes beyond simply noting that headlines about the destroyed urn were dominated by the million-dollar valuation; he rightly points out that the valuation itself is wildly overblown. Its origin defies logic—for one thing, the police never consulted the museum’s curatorial department, contenting themselves instead with an appraisal from the security staff—but its media proliferation makes perfect sense. Far more effective to lure clicks with a seven-figure fine art apocalypse than with the piece’s creator proclaiming, as Ai did in an interview with the Associated Press, that the million-dollar valuation is both “exaggerated” and “a very ridiculous number.”

Here lies the issue: Very ridiculous numbers now saturate the art market, especially the contemporary sector. Last year alone, Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog (Orange) set a new high price for a work by a living artist when it sold at Christie’s New York for $58.4M. The same night, a three-panel portrait by the 20th century master Francis Bacon reached a new sales apex for deceased artists at $142.4M. And to combat any notion that those records were uncharacteristic of the wider field, the TEFAF Art Market Report estimated the fine art industry’s 2013 gross at a knee-buckling $66 billion, with 46% of that sum (about $30 billion) coming from contemporary art sales alone.

How did this happen? Between the 1980s and mid-2000s, fine art caught the hungry eyes of two groups. The first was Wall Street, from Reagan-era traders to 21st century hedge-fund managers; the second was a vanguard of global plutocrats, from the Japanese real estate speculators of the late ’80s to the Russian oligarchs, Chinese money launderers, and Gulf state oil titans of today. Meanwhile, a subset of increasingly entrepreneurial and profit-minded gallerists raced toward this new clientele’s vaults with their safe-cracking kits in hand. As Marc Glimcher, President of mega-gallery PACE recently noted at the opening reception for his new Menlo Park outpost, “That’s how [the art collecting phenomenon] happened in the hedge-fund world. Twenty years ago, [fellow gallerist] Larry Gagosian put a big black X on the foreheads of every big fund manager, and went one by one.” Influenced over the decades by the gallerists’ outreach efforts and their own compulsion to harness every available market inefficiency, these high (and ultra-high) net worth individuals warmed to the notion of blue-chip artwork as an alternative asset class, a combination of tangible trophy and high-ceilinged investment opportunity.

The past ten years in particular have seen the members of this untouchably wealthy ecosystem, whom I refer to as Collectors Only In Name (or COINs), begin battling one another at an accelerating pace in galleries, auction houses, and art fair booths worldwide. Kelly Crow, Sara Germano, and David Benoit of The Wall Street Journal put the whole landscape in focus (in the hedge-fund link above) when they wrote that:

[The current art market] represents a major shift from a decade ago, when only a handful of Wall Street investors… were even going to auctions, much less buying art. Now, dozens of hedge-fund managers are joining the fray… Differing tactics abound, but taken together, this group of hedge-fund collectors arguably influence the prices and popularity of the world’s top artists—from mainstays like Claude Monet to newer hits like Jean-Michel Basquiat—to an extent unmatched by all but emirs and oligarchs.

Nor is the goal simply to acquire work. Instead, the objective is often to flip it as quickly and lucratively as possible. Crow et al again:

Nearly all [hedge-fund art collectors] are applying their day-job tactics to their art shopping, dealers say… Corporate raiders a generation ago typically held their art purchases for at least a decade. Today, the average holding period for contemporary art is two years, according to a former Sotheby’s specialist. That is enough time to reap a tidy profit on a rising-star artist but hardly enough for art history to rule on the artist’s lasting merits.

The crassness and commoditization fueling today’s art market make its ‘80s version look as quaint as a working class garage sale. Take it from someone who lived in both. Charles Saatchi, the advertising deity and renowned contemporary art collector/impresario, opened the Saatchi Gallery in 1985 to exhibit works from his vast personal holdings in a public venue. He spent most of the ‘90s collecting, funding, and promoting Damien Hirst and the other controversial Young British Artists; the scandalous group exhibition Sensation, for which Rudy Giuliani famously threatened to defund the Brooklyn Museum, consisted entirely of works from Saatchi’s collection. But in a blistering 2012 op ed, Saatchi declared that “[b]eing an art buyer these days is comprehensively and indisputably vulgar,” and “even a self-serving narcissistic showoff like me finds this new art world too toe-curling for comfort.” For a better sense of what triggered his gag reflex, one can look to this interview with self-proclaimed “cultural entrepreneur” and unapologetic art flipper Stefan Simchowitz, the early leader in the art world for the most infamous feature story of the year.

Far from remaining a private feast for individual investors, the frantic spending on contemporary art has even lured financial institutions to the table. Art funds have been established to assist clients in maximizing returns on this nascent investment platform, and art financing, usually offered by private banking divisions catering to the needs of high net worth clients, now offers collectors the option to use artwork as collateral for loans. Just recently, Goldman Sachs extended federally indicted hedge-fund manager Steven A. Cohen of SAC Capital Advisors a line of credit backed by $1B worth of Cohen’s art. Practically no single component of that sentence would even make sense to an art professional thirty years ago, but this is the current state of the industry.

Yet the economics of artwork as investment are just as precarious as they have always been, if not more so. The COINs tend to treat the art market like the stock market, despite that artwork lacks any fundamentals to guide its valuation. It generates no revenue; it lacks a balance sheet; it owns no assets, carries no debt, and offers no cash flow. Like baseball cards or comicbooks, art’s monetary value is determined by whatever a buyer can be convinced to pay, often based on no more than a narrative and the aphrodisiac of competition. It’s this uncomfortable truth that New Yorker art critic Peter Schjeldahl encapsulated as “the spooky assumption that art is worth anything.”

Still, staggering sums of money continue engorging the art market. They’re just not necessarily trickling down to the lower tiers of the hierarchy—tiers that include (but are not limited to) frustrated, little-known strivers like Maximo Caminero. There is a sense that this phenomenon is governed by circular reasoning: Only the most expensive artworks matter, and what makes them matter is that they are the most expensive. Respected artist and activist William Powhida captured this concept in the press release for his recent solo exhibition Overculture, which doubles as his term for the artists and collectors dancing at the market’s peak, where “price functions as a single variable for the success (or failure) for the participants” in “a closed system of exchange between members that ceases to be relevant to the larger culture.” Referenced for context by Thomas Micchelli of HyperAllergic in his review of the exhibition, Powhida’s earlier drawing Oligopoly Revised (2011) is in many ways a direct visualization of the same idea: ““a densely layered art world food pyramid topped by billionaire collectors while ‘The Yearning Unselected * You Are Probably Here’ sink to the bottom.”

This undercurrent of alienation now courses through the non-elite ranks of the art world, particularly among gallerists and artists trying to build a sustainable career without the aid of pre-existing industry connections or deep-pocketed financial backers. Journalist and general polymath Anthony Haden-Guest summed up the situation in familiar language when he wrote in April that “the [art] market is subject to the 99/1 effect, as most markets seem to be these days. What I mean by this is that there is generally one percent of winners… and then there is everybody else.” It would be an overgeneralization to say one hundred percent of “everybody else” feels equally ostracized, but neither is it uncommon anymore to believe that art has been reduced to numbers, the numbers have been inflated to nonsense, and the nonsense has pushed the overwhelming majority of participants out of the picture—perhaps permanently.

Outrage is inevitable in this context. Industry veterans decry the perceived dilution of “pure” creativity into easily marketable byproducts. Critics and scholars denounce the coverage of prices rather than principles. (Never one to put his sidearm on safety, MacArthur “genius” grant winner Dave Hickey of Air Guitar fame explained his (semi-)retirement from art criticism in late 2012 by quipping, “Art editors and critics—people like me—have become a courtier class. All we do is wander around the palace and advise very rich people. It’s not worth my time.”) Artists struggling to find an audience—especially one whose patronage consistently returns a living wage—savage elitism through their own work, or deliberately evolve their output to transgressive extremes. Occasionally someone even goes overboard, vandalizes a blue-chip artist’s work, and makes headlines for a few days.

Ai’s shattered urn is only one recent casualty of this trend. Less than a month after Caminero’s criminal mischief at the Pérez, a disenfranchised artist named Joseph Magnano used a paint sprayer and an arsenal of handmade signage to wreak havoc on the iconic Prada, Marfa installation by the celebrated duo Elmgreen and Dragset. In late 2012, Vladimir Umanets, another unknown artist, tagged his name and a short self-promotional message onto one corner of the Mark Rothko painting Black on Maroon at the Tate Modern. In 2001, a self-proclaimed “genuine artist” named Jacqueline Crofton egged The Lights Going On and Off, an installation inside the Tate Britain by Turner Prize-winning contemporary artist Martin Creed. Crofton explained her actions after the fact by declaring, “What I object to fiercely is that we’ve got this cartel who controls the top echelons of the art world… and leave [sic] no access for painters and sculptors with real creative talent.” Yet all of these rebels remain powerless to derail the money train. Just like in Earle’s game, anyone willing and able to bloat the numbers has no antagonist to hold her back.

Even the use of the reckless, (approximately) million-dollar valuation in Ai Weiwei Whoops! strengthens its connection to the new business-oriented art world. The myth exemplifies what Werner Herzog calls the “ecstatic truth,” a factual misrepresentation that illuminates a larger, more meaningful point by virtue of its inaccuracies. The higher the multiple, the quicker the player’s property damage total can fly into the realm of absurdity—just like those record auction prices and the art market as a whole. Earle even augments the effect by omitting commas from the sum, making the number’s actual meaning all the more unreal as it swells toward infinity.

Growing that total may not qualify as a game in the formalist interpretation of the word. But the enlightened “non-gameness” of Earle’s work is precisely what makes it so vital. Were it to obey the strict rules that established and popularized the medium early on, Ai Weiwei Whoops! may have peaked as a clever riff on current events and past aesthetic theory. By rejecting those same rules, it has instead become perhaps the stealthiest and most succinct simulation of the contemporary art industry today. The rampant accumulation of dollar value often looks like the only goal; the financial returns confirm that the mechanism to achieve success is in place; and the path forward seems free of any antagonist equipped to change its course. Every player of Ai Weiwei Whoops! is thus confronted with the same choice facing any open-eyed individual considering a life in the art world’s lavishly funded, top-heavy, present-day incarnation: If endlessly ringing up numbers is all that’s left, then how long do I really want to play?

Photo credit: VicPhotos, mookiefl, kertin1407