French philosopher Guy Debord talked about the idea of the dérive, a mode of travel where the journey itself is more important than the destination, where travelers “let themselves be drawn by the attractions of the terrain and the encounters they find there.” But to think of dérive as a kind of random stroll dominated by chance encounters would be to miss Debord’s essential point: spaces, by virtue of being inhabited or shaped by humankind, possess their own “psychogeographical contours, with constant currents, fixed points and vortexes that strongly discourage entry into or exit from certain zones.” Spaces can be designed. They can be made to promote certain pathways, encourage specific behaviours, even elicit emotional reactions.

While impactful, this idea isn’t new. Humans have been engineering the social and psychological affordances of architecture and urban planning for centuries. For example, archaeologist Michael E. Smith argues that empires such as the Aztecs, with their neatly orthogonal capital city of Tenochtitlan, used city planning both to reinforce the cosmological beliefs of the Aztec religion, and to legitimize the political authority of the empire among the people.

In fact, if we take into account humankind’s original role as both a predator and a prey species among the vast savannahs of Africa, it isn’t hard to posit that a powerful awareness of space and place is intrinsic to our humanity. In fact, psychologists Yannick Joye and Jan Verpooten do just that, taking a Darwinian approach to analyzing the role of monumental architecture. They assert that the erection of what Michael Smith describes as “constructions that are much larger than they need to be for utilitarian purposes,” both a) parallels threat displays in the animal kingdom, signifying the might of the builders, and b) exploits our natural sensitivity for “bigness” to instill feelings of awe. In other words, we are biologically programmed to be highly sensitive to space, place, and location.

Mice and Mystics image via Flickr.

Games and Spaces

Spatial design is so important to us, that its principles transcend even the physical world of architecture and enter the fictional realm, especially that of games. the In the 1940s, Dutch historian Johan Huizinga published his ideas about the “magic circle”; a “consecrated spot” where play occurs (“the arena, the card-table… the tennis court”). Taking into account Huizinga’s ideas, you can argue that, fundamentally, the act of playing a game is the act of delineating a boundary that separates the mundane world from a mystical, created one—a world that is governed by rules different from everyday life. The concept of the “magic circle” applies even more to games that try to tell stories: any such game is unavoidably about the ‘where’ that the story takes place in.

Think about children playing make-believe, overlaying the real world with imaginary landmarks, superimposing an impenetrable citadel onto a jumble of pillows, varnishing a gnarled tree with magic and mystery. Similarly, sitting down for a rousing game of Dungeons & Dragons, is essentially about plunging into a fantasy world of enchanted forests, sinister dungeons, and caverns that stretch deep into the earth, ripe for exploration. Any boardgame that carries even a shred of narrative either includes lush artwork featuring the locations you visit, or force the creation of a psychic space: take the beautifully detailed stone floors of Mice and Mystics (2012), or the wind-tossed dragons of the minimalist game Tsuro (2004), that hurtle through only the open skies of your imagination.

Videogame designers, of course, often choose to focus a great deal on setting. The Mushroom Kingdom in Super Mario Bros. (1985) has a very particular aesthetic; BioShock’s (2007) underwater city Rapture is frightening and sad, and the upcoming No Man’s Sky promises a gargantuan, mathematically-generated galaxy brimming with impressionistic landscapes. But more than just provoke an emotional response, carefully constructed spaces allow for a different kind of storytelling. “Environmental storytelling”, where spatial elements are used to reveal or further the story, has become somewhat of a buzzword within gaming circles. As media scholar Henry Jenkins puts it, “…a story is less a temporal structure than a body of information… a game designer can somewhat control the narrational process by distributing the information across the game space.”

Videogame designers, more than almost any other art creators, are furnished with near-limitless options regarding what they can do with the spaces they create, as well as what happens to the players who choose to inhabit them. They can, very literally, fashion any sort of space they care to dream. But for all this power, and all the narrative potential of space and place, most videogames follow a fairly traditional route to storytelling, using the space only to supplement a linearly (as opposed to spatially) told narrative. “Generally speaking,” argues Jamin Warren about videogame stories on the video series PBS Game / Show, “games are fairly straightforward when compared to other mediums.” If you look at other entertainment and artistic media, examples of unconventional storytelling structures abound. Dhalgren, science-fiction behemoth Samuel Delaney’s hugely successful 1975 novel, is mind-bogglingly circular in its narrative construction. Christopher Nolan’s Memento (2000) would be a far less compelling film if watched in chronological order. And readers of Neil Gaiman’s towering Sandman series of graphic novels are used to drifting dreamlike between different time periods—the latest book, The Sandman: Overture, is set simultaneously before and after the conclusion of the original series. Unfortunately, within the realm of digital games, where unusual narrative structures would assumedly be easier to create thanks to the magic of computer code, such variety is infrequently encountered.

Theater and Immersion

Paradoxically, some of the most interesting examples of non-linear, environmental storytelling seem to be taking place in the medium where space is the most difficult to engineer: the real world itself. The increasing popularity of “immersive theatre” experiences, where audiences are physically brought into elaborate sets designed to be explored, reveals that engaging stories can indeed be communicated through space. And I don’t just mean visually. Scott Palmer, quoted in Josephine Machon’s 2013 book Immersive Theaters: Intimacy and Immediacy in Contemporary Performance, describes immersive theater as a “phenomenological multi-sensory experience of place,” where, “visual, oral, olfactory and tactile elements become an integral and often heightened part of the audience experience.”

Immersive shows can be seen as a natural extension of the practice of theater. Throughout its history, the theatrical world has been highly concerned with representations of places. Even in London’s famous Globe theater, for instance, with its minimalist sets, Macbeth’s Duncan made sure to loudly proclaim, “This castle hath a pleasant seat,” lest his audience forget where the action was set.

One of the most famous immersive theatre companies is the English Punchdrunk, whose sprawling, macabre experiences have gained international repute. In many Punchdrunk shows, audience members are left to wander an expansive, often ghoulishly eerie landscape in a kind of Debordian dérive, drifting where their interests, the characters, or currents of other viewers take them. Interestingly, Punchdrunk’s works are themselves influenced at least somewhat by videogames. When talking about one of their shows, Punchdrunk’s artistic director Felix Barrett told The Guardian, “It’s similar to how in Skyrim you can follow a character and go on a mission, or you can explore the landscape, find moments of other stories and achieve a sense of an over-arching environment.”

The Case of Sleep No More

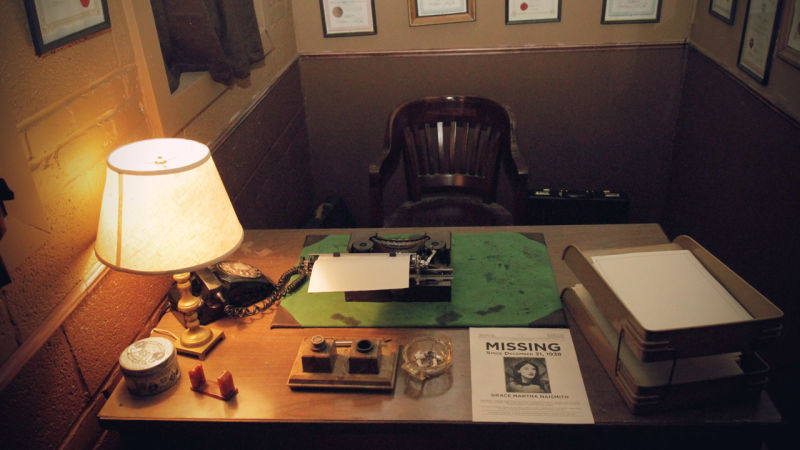

Parallels to games are hard to miss in Punchdrunk’s most talked about show Sleep No More, a 1930s, Hitchcockian version of Macbeth taking place in a set of converted warehouses in Chelsea. Their fictional McKittrick hotel is an open-world game, where visitors can set their own pace and choose what to see. Secrets can be discovered in hidden corners; one-on-one interactions with characters can be “unlocked” by being in the right place at the right time. You even experience Sleep No More as a character: viewers are asked to don bone-white masks at the start of the show, divorcing their “self” from the shadows or ghosts that they must become to fully immerse themselves in Punchdrunk’s world, and make decisions that only an in-game character would. In Felix Barett’s words (quoted in Machon’s book), the masks allow participants to be “empowered because they have the ability to define and choose their evening without being judged for those decisions…they have the freedom to act differently from who they are in day-to-day life.”

(Source)

But it’s Sleep No More’s almost textbook use of environmental storytelling techniques that’s really intriguing. Henry Jenkins describes four main ways in which in-game environmental storytelling “creates the preconditions for an immersive narrative experience,” three of which are heavily used by Punchdrunk:

1) “Spatial stories can evoke pre-existing narrative associations”

Almost everyone who attends Sleep No More has some notion of the Scottish Play’s basic plot. The show’s scenic design specifically reinforces the noir-Shakespearian world you’re in. Hecate’s apothecary is a good example. If you stumble into it, likely guided by the scent or sight of dried herbs and preserved animal parts, you will almost certainly make the connection to the three witches from the play, and perhaps even recall a few lines from the famous Witches’ Song. If you stay a little longer, you may even notice a thematic resonances between all the natural materials and Macbeth’s impending doom: “Nature has this huge power within this play, this sense of destiny and nothing you can do to stop it,” Felix Barrett told the New York Times, while describing the room. “Things are collected, crafted and manipulated.”

2) “Embed narrative information within their mise-en-scene”

Punchdrunk clearly ascribes to preeminent dramatist Antonin’s Artaud’s “less text, more spectacle” philosophy of scenic design: every space within the show is redolent with objects that convey story in a number of different ways. Participants may discover artifacts that contain text and image that further the story, such as Macbeth’s letter to his wife that participants can find and read. They may find clues that suggest events that may have taken place, such as the murder of Macduff’s children, revealed through the bloody sheets in their nursery. But sometimes, objects embedded into the show are bridges to outside micro-narratives, to be guessed at, pondered, wondered at. The bleak hospital room, for example, is filled with hundreds of locks of human hair, each carefully catalogued and stored. “This is very much the outer reaches of our world…there’s implied narrative…” Barrett recounts, “…many, many stories of people, the backstories of the characters…”

3) “A staging ground where narrative events are enacted”

Macbeth ends an agonized solo dance in a graveyard by dangling from a tree like a hanged man. Duncan, right before his murder, discovers a room filled with dozens of clocks, all striking midnight at the same moment. Clearly, spaces and set pieces can be used to enhance the story being told. But, concentrating solely on this “enhancement” would be to only shallowly engage with Jenkin’s point, and to ignore some of the most interesting, and also the most underutilized (especially in the gaming world) techniques of spatial storytelling.

Jenkins reminds us that the environment itself can direct the flow and rhythm of the story. Dramatic lighting, the architecture of the space, the echoes of music and sound through doorways, stairways, walls and ceilings; in addition to contributing to an atmosphere and emotional palette, all of these are also all used to guide participants through the scenes of Sleep No More. There is no one path being the “correct” or “best” way to experience the story, and seeing every scene within Sleep No More is almost impossible with just one viewing. Some would even argue that this is a trope within immersive theater, that visitors never get a “complete” picture of the story.

Rather, spatial design provides participants the freedom to forge their own routes, to glimpse parts of the story that perhaps no-one else notices, to weave together the nonlinear collection of narrative fragments that is unique to each individual’s experience and create one’s own interpretation of how they’re all connected. During a lecture at GDC 2015, game designers Matthias Worch and Harvey Smith reminded us that, “environmental storytelling relies on the player to associate disparate elements and interpret [them] as a meaningful whole.” Through individual journeys and personal synthesis, participants and creators almost become collaborators in telling a story. Which is, of course, the goal of many games.

The Case of Gone Home

It is precisely this “association of disparate elements” that can be used in the videogame world to tell more interesting, nonlinear, spatially-oriented narratives. Out of the few games that use this technique, one of the most talked-about examples would be The Fullbright Company’s 2013 release Gone Home.

Gone Home is a rare example of a game that was inspired by a theatrical piece, which was itself inspired by games: scholars Daniel and Sidney Homan inform us that the designers of Gone Home were heavily influenced by Sleep No More. They quote designer Steve Gaynor, who feels that in Gone Home, “players, like theatergoers, can choose where to focus their attention,” and that the “audience…occupies the same three-dimensional space as the fictional inhabitants.”

Gone Home is a first-person exploration game where players take on the role of Kaitlin, a college-age girl in the 90s, who returns home to find that all her family members have gone away. Much like in the best examples of immersive theatre, players get to explore the house and its contents, absorbing narrative chunks until a clearer picture of the story emerges. There are no enemies to defeat, no scores, no competitive element; the objective is simply to discover more of the story.

And even more so than in Sleep No More, much of Gone Home’s story is told through environmental elements. Yes, there are examples of recorded voice-overs that reveal snippets of the main mystery in the game, but to focus only on those would be to miss much of the rich layers of story built into the game. As vlogger Rantasmo explains, “it’s a game about people and objects, and about who those people are through the objects that they own, and the very deliberate way in which they’re placed.” Not married to the trope of cutscenes, some of most intriguing parts of the story are scattered around the house, in the form of letters, newspaper clippings, pamphlets, homework assignments.

But it’s not just textual relics that reveal the story. No, you can literally pick up and play around with the most banal of items. Empty binders, toilet paper, a model duck… Homan and Homan even contend that the presence of such everyday items is “crucial to establishing real emotional connections between the gamer and his onscreen representative.” Then again, some objects do reveal significant pieces of the story. Piles of Kaitlin’s father’s first book languish all over the house, evidence of his brief flash of fame as a writer. A Ouija board hidden in a secret panel points at attempts to contact the spirit of a dead relative. A tender photograph of two clutching hands is a testament to adolescent love.

Once again, you as the player are made keenly aware of the space you’re in, though this time, the lights, sounds and textures adorn a virtual world rather than a material one. There’s a childish thrill in discovering and traversing the secret passages that dot the house. Entering Kaitlin’s parents’ room feels vaguely transgressive. And finally reaching the attic, the one marked from the very start with signs and coloured lights, really does feel like the end of the game, a triumphant ascension to glory, high above the mundane trappings of the rest of house.

And once more, just like in Sleep No More, much of the story, much of the tying together of narrative strands, is left to you. Not all the narrative dots are connected for you and the game leaves a fair amount of wiggle-room in terms of what might have happened. Did your mother actually have an affair or are you just fancifully implanting unnecessary drama into the situation? Is the copy of Leaves of Grass (1855) you found indicative of some sort of midlife queer awakening in your father, or are you reading too much into it? Gone Home doesn’t care to tell you. What it does care to do is leave breathing room between each revelatory discovery, giving you time to mull over what you found, time to create your own links.

And therein lies the key difference between The Fullbright Company’s quiet little game and Punchdrunk’s grand spectacle. In Sleep No More, visitors are constantly on the lookout for references to Shakespeare, or nods to Hitchcock. While the piecing together of the story elements is a personal experience, it’s always coloured by the presence of the reference material. Gone Home, on the other hand is virgin territory. A player goes in tabula rasa, armed only with genre tropes (many of which are playfully upended). Using signposts and hints supplied by the designers, players fill in all the gaps in the story within their own heads, because the game leaves you somewhere in between knowing and not knowing all the details. Even Felix Barrett comments on this: “Gone Home has an implicit narrative,” he told The Guardian. “You’ve either just missed the action or it’s just about to happen and you’re suspended in-between.” It’s this kind of nonlinear, almost emergent form of storytelling that makes Gone Home stand out from other videogames.

Non-linear stories, non-linear games

Humankind is obsessed by the concept of space, owning it, controlling it, changing it. Yet, even with our relentless quest to shape the spaces around us, so are we changed by them in turn. In his essay, Guy Debord quotes Karl Marx’s famous line: “Men can see nothing around them that is not their own image; everything speaks to them of themselves.” All around us, spaces are constantly filling up with stories, messy, nonlinear stories with no clear beginning, middle or end, stories of which we catch only fleeting impressions, stories that we each absorb and interpret to fit our own personalities.

If interactive experiences like Gone Home and Sleep No More, both of which defy their genre expectations (Is it a play or a game? Is it a game or a film?), have anything to teach us, it’s that we can very much rely on audiences to fit pieces of the puzzle together, and even to come up with their own, uniquely shaped pieces to fill in the holes. The world of gaming can very much embrace that the “magic circle” can be defined both by the creators as well as the players.

Header image via Flickr.