Is Watch Dogs a fantasy, a nightmare, or a reality?

Welcome, friends, to the nanny state.

Every day, it seems there’s another story about government snooping. Mobile companies keep a record of everywhere we take our phones, then sell it to cops. Encrypted email is an enemy of the state department. President Obama held a press conference to assure us that the government isn’t spying on us. They’re just, apparently, looking over us. Welcome, friends, to the nanny state.

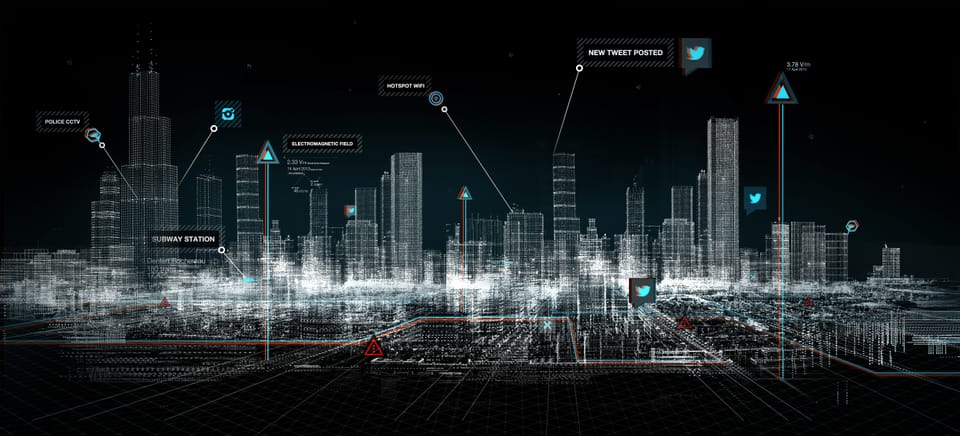

Watch Dogs asks us to consider the highs and lows of our digital future.

As dystopian thriller and fall blockbuster, Watch_Dogs ups the ante. Based in a near-future Chicago, you play as a hacktivist vigilante who toes both sides of the law. The Huxleyan question is what, exactly, will happen ten years from now, when big data drives entire cities. Does it make the world a safer, tech-savvier place, or just breed distrust? Watch_Dogs point is certain. The future could be dangerous.

So, techno-dystopia could actually happen? As Bruce Schneier, author of Liars and Outliers, tells me, “that doesn’t sound ridiculous, sure … given the definition of the word could.” This goes for things like facial recognition falling into the wrong hands, personal data being hacked from your cell phone, and breaches to city-wide security cams. Undoubtedly, there comes a surreal moment in the game, when you’re peeping through the lens at a virtual Chicagoan, and you look down at your Kinect, and realize this could happen to you. (You’re probably safe. Why would anyone want to watch you exist in a semi-vegetative state on the futon?)

Have we created a network that is in some ways bad for humanity?

I asked Schneier if all this technology could be bad for us. Of course, no security expert or self-respecting futurist wants to talk existential questions. To these guys, technology is an objective entity. The science and science fiction writer David Brin got prickly when I brought up the subject, telling me to go reread his book, The Transparent Society. (More on him later.) Schneier told me the issue doesn’t even interest him.

“You can use [technology] in any direction. All these things depend on how they’re being used,” Schneier says. “They’re not [inherently good or bad] out of the box. Think about facial recognition software. In some ways it’s no different than people recognizing each other, only it automates and scales in ways you can’t.” Tech is impartial, simply put.

Watch_Dogs also subscribes to that line of thinking. “We’re not saying that this is evil or that this is good,” the game’s lead writer Kevin Shortt said in a recent interview. And his sentiment was echoed by the game’s content director, while speaking on a panel at Comic-Con. “Technology is the progress,” he said. “People are using it. Some people will do things the right way. Some people will do things the wrong way.

He can steal a ride and swipe a few grand from an offshore banking account, or he can be a 21st-century Edmond Dantès.

So, it’s all on us. This aligns pretty flush with the game’s sliding morality scale. The player can use his hacker skills to help or do wrong. You can swipe a few grand from an offshore banking account, or become a 21st-century Edmond Dantès. “The main question is who watches the watchers. How can we regulate that?” content director Thomas Geffroyd said.

This also fits with David Brin’s views on sousveillance; specifically, that a general public armed with ubiquitous cameras is our best defense against unjust surveillance. We just need to turn those cameras on the authorities—to become watchdogs, so to speak.

“I consider privacy to be an essential human desideratum, though we will have to redefine it,” he tells me. “And the best way to save some privacy will be if we empower everyone to see almost everything.” This also applies to shady dealings like data collection, at least in theory. While the internet enables the N.S.A. to snoop, it also allows whistleblowers like Edward Snowden to use that same technology to achieve transparency. It’s a two-way street.

A general public armed with cameras is our best defense against unjust surveillance.

But does it really prove that all this modern tech is blameless? Maybe, maybe not. As the executive editor of Wired, Kevin Kelly’s views on technology can get weird quickly, hinging on a belief in a super-organism called the “Technium,” a collective body built of smaller technologies, which in its own simple way has a will, like a flower turning towards the sun.

My point is that his ideas have spiritual connections. Kelly told Boing Boing, “I found the guys who were making the God games and stuff to be tremendously powerful metaphors for understanding religion.” He believes creators are accountable for their virtual creations. A valid complaint about modern games is that game-makers play the neutrality card too readily, using the openness of “open-worlds” and bifurcation of “morality systems” as a way to dodge responsibility for the metaphors they create. Now, I see why. This is how we’ve come to look at technology.