Yung Jake is sparse in his texts. Condensed speech and and internet slang find their way in many of his messages. Splitting his brain in two to uncover his motivation and inspiration for his work was, funnily enough, very difficult via text message interview. (It was the only way he’d communicate with me for this story.)

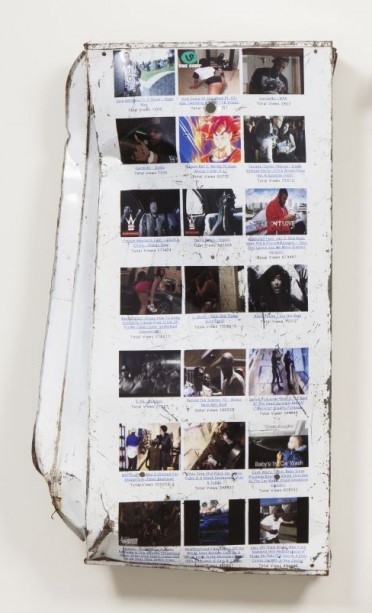

Where you will find Jake’s voice is in his art, the vivacious lyrics of his songs “Look” or “Datamosh,” the digitally charged visuals in his music videos, or his recent sculpture exhibition titled New at Steve Turner Contemporary. The exhibition features many aspects of our lives online, including Youtube videos and advertisements plastered onto earthy scrap metal. His art is so loud in its declarations that it doesn’t need explanation; in fact, he won’t explain it. New rings a powerful chant in our ears, that we are deeply rooted and astounding obsessed with the inescapable grasp of the world wide web.

“I wasn’t really born on the internet,” Yung Jake texts, stating the obvious while simultaneously crushing my love for a good metaphor. The press release for New points that Yung Jake was born to the internet in 2011, and though it may not be biologically true, it certainly has truth for him, and for many of the rest of us, too.

Because, while no computer can birth a human child (thanks Jake), for many of us, the dependence we feel for lying fingers on a keyboard, for glossing our eyes with a computer screen hue can feel as intimate as a mother and child connected by the umbilical cord. The amount of children growing up with computers in their households are ever-growing; you see a baby in a stroller with a tablet and gasp at his ability to swipe and click with quickness and confidence.

“No I just meant [I] was created in 2011 for the internet.”

The two worlds have blurred, and Yung Jake is a voice for the new world they’ve created. Surfing the web is no longer a solitary act, but a worldly event that connects most people to each other. Yung Jake’s New exhibition helps bring to life the bridging gap between the virtual and real worlds. Jake shows that our beloved games, phones, and computers that we frequent are more than gateways to escape from the monotony of real life; they are real life.

One piece titled “Old” prints a list of Youtube videos on scrap metal. Another titled “Internet Skeleton” posts a Shutterstock image of a skeleton also on metal. Even a tangible, human skeleton has found itself plastered onto the digital realm. The internet is in our blood, and Yung Jake works to display our dependence on the web and its wonders.

He says the exhibition is not meant to condemn or praise our lives in the virtual world. But he also admits that he isn’t entirely sure whether or not the importance we give social media is good or bad, but as long as it causes people to think, then at least that is good. As Jake helpfully notes, “It’s def good to be thinking.”

New reminds us that the relationship between the tangible and intangible are not two separate entities. Like games, the internet should not be disregarded as mere escapism. This is how we connect, how we relate, how we communicate.

While talking about games, Yung Jake compares his childhood love for his Nintendo Game Boy to how he uses his phone to day: “Growing up I traveled a lot and I was the type to always be on my GameBoy. And I’m kinda the same now with my phone.” Of course, the two share many traits: gaming and technology help create worlds for us to live in. And even now, the two are merging, as mobile games rise in popularity and phones have turned into a platform for digital experiences . As technology grows, so does our love for it.

New reminds us of this path. It may look silly to see a Vevo sign on a piece of metal, but it’s sobering, too. The internet is becoming as much a part of this earth as the metal around us.

Yung Jake’s exhibit may have ended, but you can find his music on Youtube or a viewing of his exhibition on Steve Turner Contemporary’s website.