John Clowder considers himself a disciple of Czech filmmaker, artist, and surrealist Jan Švankmajer. It’s he who Clowder attributes much of his artistic learning to.

“Remember there is only one form of ‘poetry’,” Švankmajer wrote in his decalogue. “The opposite of poetry is professional expertise. Before you start making a film, write a poem, paint a picture, create a collage, write a novel, essay etc. Only by cultivating your ability for universal expression will you ensure you will produce a good film.”

Clowder isn’t making films—his current pursuit is videogames—but Švankmajer’s thesis and Clowder’s creative approach are one and the same. As such, in as far as the arts are concerned, Clowder is approaching the status of a polymath. He used to aspire to literature, he has composed a great many songs, put his fingers to fey animation, and continues to be enthused by pencil drawings and fine painting since being introduced to it by his mother as a child.

The term “polymath” may have a more accurate substitute in a profile of Clowder, as it’s collage that he primarily practices and, you could argue, also embodies through his many artistic talents. He is a collagist.

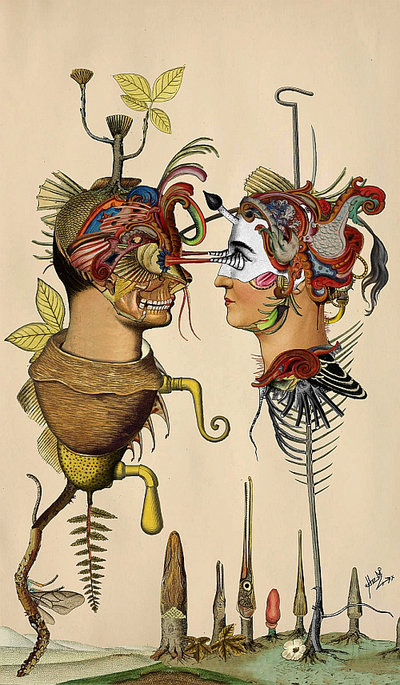

In his 2011 “Collagist Manifesto,” Clowder referred to collage artists as scavengers, as they prise the completed works of others—”obsolete adverts, morbid medical texts, bone atlases, and zoographic curios”—from their creator’s grip in order to remix them into new sights and sounds with their meat-ripping claws. Collage is a technique that finds a metaphorical and physical commonality with the assorted dead skin and stolen organs of Frankenstein’s exquisite monster. “Consequently, bone and exposed flesh are kindred to collage artists as they are our familiar inheritance, and it is mostly from these elements that I composed my creations,” writes Clowder.

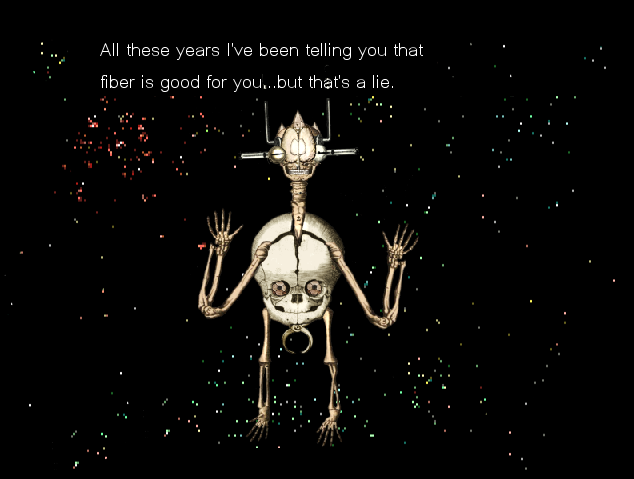

This manifesto was written before Clowder had released Middens, his first videogame, but it is as relevant to his current project as it was to his initial leap into the medium back then. Middens was Clowder’s concept piece, an experiment to see if collage and pixel art could work as a central aesthetic in a videogame. It’s inhabited by sundry, forlorn monsters that you had the option to kill or let live out of sympathy. Your decisions affected your position within the karma system, and your closest companion, a talking revolver with bright red lips, tended to tempt you toward sinful actions. Clowder’s holistic description of Middens is more revealing of his vision for the game, it being “the explorations of an enigmatic space rift quartered out of discarded sectors of God’s universe.”

His second videogame, Gingiva (originally titled Moments of Silence), started off as a continuation of the ideas put forward and explored in Middens. It was, at first, described by Clowder as a “satire for futurists interested in string theory,” which must refer to the game’s penchant for disorienting multi-dimensional exploration. With Gingiva, Clowder established this perplexing open-world structure as his own manifestation of collage inside the parameters of a videogame—the player pieces together their own experience from the sandbox he has laid out and filled in. Clowder also uses vignettes, anecdotes, and his original creature designs to further embody the mix-and-match format of collage inside his games.

For his third videogame, titled Where They Cremate the Roadkill—which he’s currently seeking crowdfunding for on Kickstarter—Clowder suggested to me that he is trying to divorce himself from the linear progression of his style that his two prior games established. “In two you can create a pattern and with three you can break it,” he said. “Where They Cremate the Roadkill is by far the most advanced work we’ve dabbled in so far. It was nearly six years ago that I began work on Middens. In my opinion it is as much a leap from these earlier titles as 8-bit was to 16-bit.”

Here, Clowder places himself as being so removed from the traditional videogame canon that he is able to write in a new, parallel ancestry for the medium. Rather than being born of the technological sphere, from which high-tech advances and

The strength of the pattern break that Clowder purports to be exploring in Where They Cremate the Roadkill will have to be judged upon playing it. For now, a distanced assessment of the game seems to prove that he’s continuing to ramp up his effort to express collage through videogames. He describes his upcoming game as being “treelike,” as its central narrative segues into branches, dispersing into twigs, with leaves being the outcome. There are “stories housed within stories, and characters hidden in characters,” he says while making a further comparison to Russian nesting dolls.

Perhaps the most appropriate comparison for the fantasy world that Clowder has created for Where They Cremate the Roadkill is the human body. Indeed, he referred to it himself when describing the game’s structure to me, but only after also calling upon the fitting imagery of “a ring of concentric circles” for further comparison. He says there’s a central event in the narrative that ripples out across the game’s three worlds or dimensions, and each of these have their own aesthetic, fauna, and phenomenon. They also have their own unique protagonist, all threaded by a common crisis, for you to control. To travel between dimensions you’ll have to find portals, and these are inconspicuous and many, disguised as a mirror, a puddle, a television screen, a sewer hole, a rabbit hole, a bed, a pile of leaves, a giant fish’s belly.

“The play here is on powers of scale; microcosms living in macrocosms,” Clowder said. “Most people think of the human body as being one unified being—but in reality it is equally a collective organism. Your own cells can rebel against you.”

You’ll be able to explore the world’s breadth by abandoning the pursuits of its central conceit (which we’ll get to in a second), just as is possible in both Middens and Gingiva, as curiosity-driven ambling is an activity that Clowder has been attached to since he was a child. “I want the player to discover a secret that feels like something no one’s ever uncovered before. There’ll be enclaves so scarcely found that players will feel a genuine sense of wonder at having met them.”

Those who aren’t wooed by rebellion, who don’t choose to chart the outer reaches of Where They Cremate the Roadkill‘s world, will be faced with the struggles of being a repo man trying to make their fortune by collecting souls that are owed to the Devil. You might think that to be an easygoing occupation, as it seems to promise a lot of power, but it doesn’t unbind you from common laws, and combat is illegal in the game’s world. This means you can’t head up to a target and battle them to the death just anywhere. If you want to get away with murder, you’ll have to do it stealthily or outside the city limits. “Lure your opponents into back alleys or corner them in their homes,” Clowder suggested. “It’s merciless and conniving in a way.”

In outlining another component of being a repo man, Clowder made a further comparison to body parts and functions, building upon his earlier idea of the world being a “collective organism.” There are spells that you acquire by assimilating others or rummaging around the environment, or inside the pockets of the slain, and they have uses in battle as well as outside of it.

“They allow the player to extensively manipulate the world and its populace,” Clowder said. “Were it raining, you could transform that rain into a deluge of frogs…you could grant pigs wings, or convert dirt into money and vice versa. They’re subversively fun, a little cruelly mischievous and there’s hundreds. Players can have as many on their person as they can use at once.”

During battle, these spells might be used as ways of attacking someone—you could turn someone into a fly and squash them, for example—and to that, Clowder said, “attacks become stronger with practice and atrophy from disuse. Like a muscle.” This makeshift memory system has you functioning almost as if a white blood cell eliminating viruses and disease from a larger body: the more you deal in a certain type of attack, the better you become at it, just as the body is able to more easily prevent an illness it has encountered before.

Once I had been introduced to the idea, I couldn’t stop seeing the game’s world as this physical collage that resembled body innards. And how could you not? It’s said that there are landmasses in the game that are carved from the corpses of primordial giants. Plus, as you shrink the city’s population, the graveyard at its outskirts grows without visible sign of any ceremony. It’s as if the land is an organ itself that transfers the dead to their grave.

And so I’m convinced that, with Where They Cremate the Roadkill, Clowder is constructing his most explicit realization yet of his theory that collage has a kinship with the framework and inner workings of the body; the “bone and exposed flesh” he refers to in his manifesto. This is the body as collage; collage as the multitudinous networks of the body. He’s pulling it all in: the teachings of Švankmajer, his years spent practising different art forms, his bizarre collage creatures, and his conceptual experiments in videogames. It’s collages inside collages. Collages all the way down.

You can help to fund Where They Cremate the Roadkill on Kickstarter.