How did words knock off Mario and flying avians to become gaming’s heroes de rigeur?

– – –

Seems like everywhere you turn, a new word game is captivating an audience of new players, eager to show off their vocab skills or challenge their co-workers. Zynga’s Words With Friends got Alec Baldwin in trouble with the FAA. Zach Gage, a previously little-known experimental artist, releases SpellTower and shows up in a New York Times Magazine article. PopCap’s early title Bookworm would pave the way for their other world-conquering efforts like Plants vs. Zombies.

So why have those twenty-six characters, learned in grade school, become more enticing to us as players than fantastical worlds and space marines?

Jeff Green, Director of Social Media for PopCap, told me why he thought a simple word game like Bookworm, a spruced-up version of Boggle for almost any platform, works so well.

It uses videogame conventions–powerups, sound, music– to keep you engaged on a level beyond that of just a digital crossword puzzle.

PopCap took a type of game that many would find almost classically boring (a word game) and gave us the “gamey” stuff that we love.

But I wonder if the difference is more than what’s been layered atop the usual field of mixed letters, but how we interact with them in the first place. Words used to be stuck to the page, stamped with ink or scratched with carbon. A touch-screen allows heretofore unparalleled interactivity with the very root of what makes us human: our ability to think, reason, and wonder, often realized through a construction of letters into thoughts.

A game like Bookworm might just be a gamified version of the simple Word Search puzzles in the newspaper. But, playing on a touch-screen, the medium through which we play it becomes as important as those conventions the team at PopCap devised to add tension or joy. A cerebral experience becomes tangible.

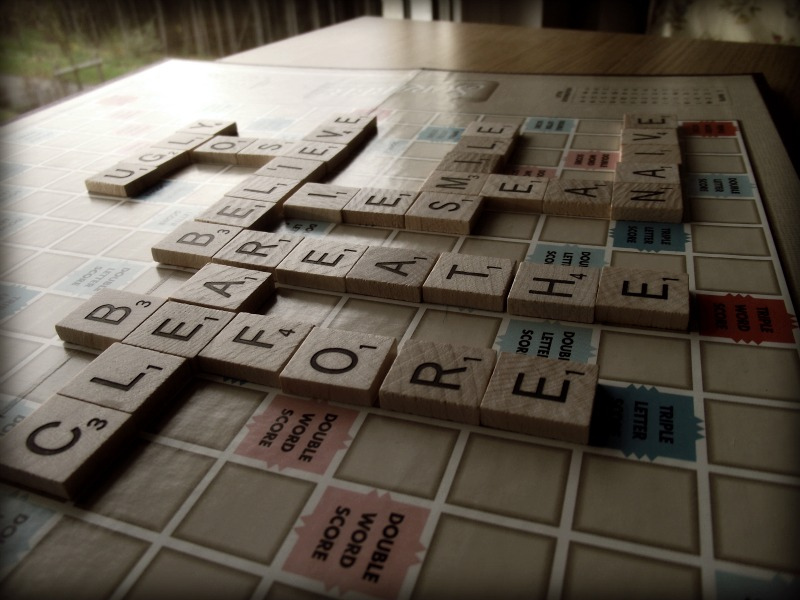

Placing a Scrabble tile has a physical weight, whereas writing a word on paper is enacting a kind of damage onto the previously clean slate, a wound that bears meaning. The prevalance of word games played on touch-screens merges these two feelings–you control language with swipes of fingers and tapped callouses, making the realm of thought malleable with our hands.

Zach Gage’s SpellTower plays with this feeling of weight and words. As you trace the right combination of letters, the thought disappears, and those uncombined bits fall down into the remaining gaps. The same game, mechanics-wise, could be played with a mouse or trackpad, but the distance between interface and interaction is too great. You have to touch these words to bring them into being.

“I think gaming tends to mirror where people are in their actual lives,” Gage told me in an interview last year. And as we see the explosive rise of e-readers, with digital sales of books fast approaching that of print, people want to engage with words through a screen. What better way than with games?

Proletariat Inc. is the latest studio to take advantage of our growing infatuation with reading digitally. Made up of former employees of the now-closed Zynga Boston, the studio is launching Letter Rush, their first game, on Apple’s App Store this Tuesday, March 5th. It combines the classic find-this-word-in-a-jumble-of-letters mechanic with the tension of Tetris’s falling blocks: Words scroll in horizontally from the right, and you need to find them in a block of letter tiles below. Wait too long and they crash, ending the session. Rush follows the PopCap method of turning classics on their head, with power-ups and a consistent flow of jangly effects squeezing out the dopamine.

But it’s the interplay of eyes and fingers, working together to manipulate information below that smooth gloosy surface, that tweaks the exercise into something more than filling out a crossword. Colored gems might shine, but letters form the very way we communicate with others and ourselves. Maybe this explains why playing with words feels so good.