The most popular videogames, the games with the largest active player bases in the world, are a familiar catalogue of famous titles. In 2010 World of Warcraft reached 12 million subscribers. Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3 was the most popular of that ubiquitous series, selling a mighty 26.5 million units. Draw Something is huge, and Farmville, and of course, Mario.

What if I told you, though, that there is a set of games that has 32 million active users in the United States and Canada alone, a population that is growing rapidly, and yet it gets almost no ink in the popular games press. Consider that researchers estimate that it might add another 5.5 to 7.5 million players in Britain alone. These games are so big, in fact, that worldwide estimations of the player population are difficult. They are the games I spend the most time playing, and have done so for over a decade continuously.

I’m talking, of course, about fantasy sports.

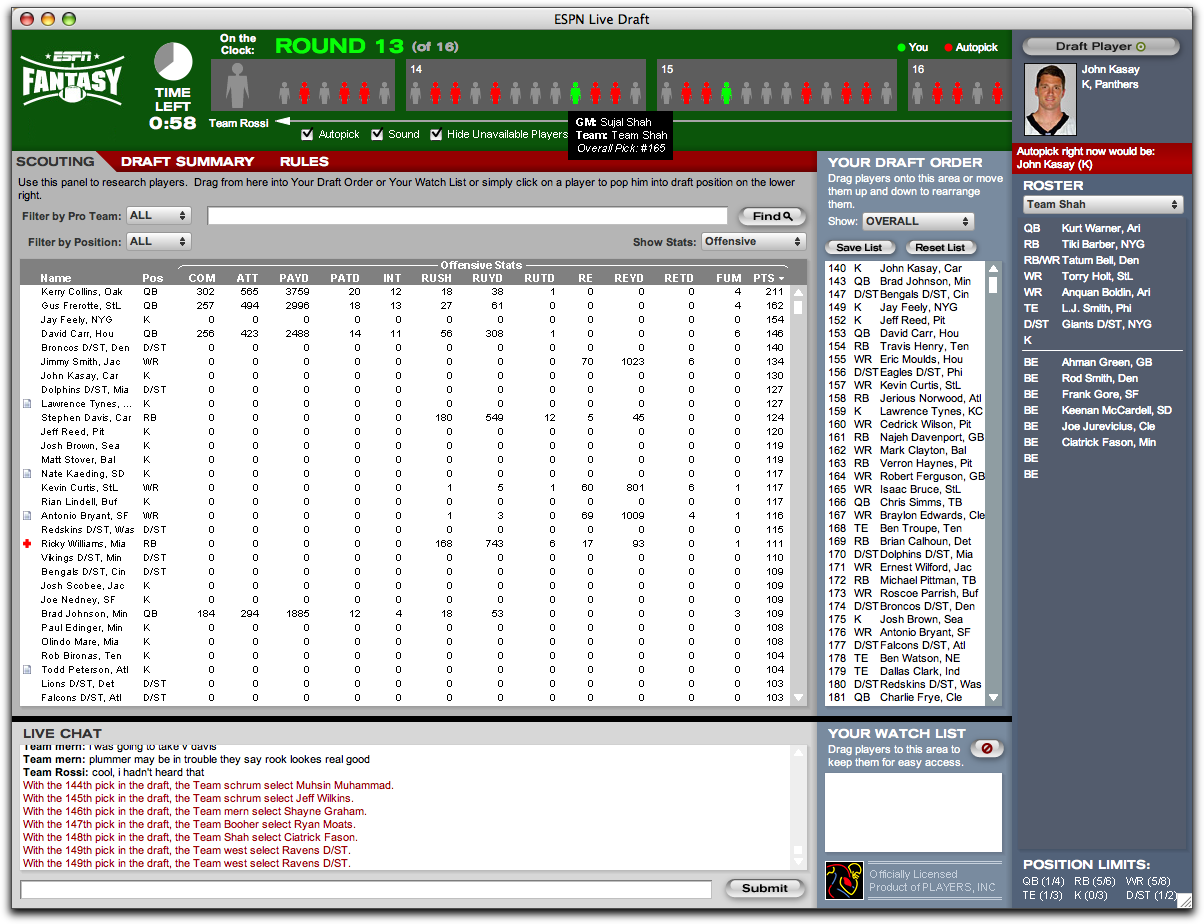

Beginning humbly as a paper-and-pencil offshoot of statistics-based board games, fantasy sports games have grown, with the explosion of the internet, into the most popular digital games in the world. There are many different kinds of fantasy sports, from large-scale, highly detailed management simulations, to more basic, gambling- inspired “pick the winner” games. The two major hosts of fantasy sports games, ESPN and Yahoo, are known largely for their other types of content, and yet every day millions of players point and click their way onto fantasy sports servers to manage their teams, set up lineups, add and drop players, and wheel and deal.

Fantasy sports, from a game design perspective, are a fascinating specimen. They often feature complicated and highly nuanced game architecture built on a foundation of statistical analysis. While some fantasy leagues rely on default settings established by the game hosts, many are highly self-regulated and organized.

For example, the baseball league I’ve been participating in for 12 years begins each March with a player auction, in which all the team “owners” bid on players, filling their team while spending their limited in-game budget. We use the software infrastructure of ESPN to run the auction, but our ruleset transcends the options available from the host website, and so we keep a collection of data on Google spreadsheets. Most of us spend hours a week (sometimes a day) organizing our valuation of players, speculating on who might be undervalued in our mini-market, and preparing a plan for putting together a winning season.

We talk about strategy, but we also debate the rules in our league. We change a few rules almost every year to accommodate our collective interests. And that’s just baseball. I’m smack in the middle of my fantasy football season right now, and I’m in two leagues, which I can barely manage to keep track of. One can imagine how deep the rabbit hole goes, and I’ve definitely fallen in head-first.

Game criticism has come a long way in the past five years, and sites like this one are a testament to that growth, and yet I wonder why there is such a glaring blind spot ignoring fantasy sports. Why have we not turned our critical gaze onto these immensely popular, and truly fascinating game systems? Chuck Klosterman recently wrote for Grantland about the effect of fantasy sports on sports fandom, but that is for a largely sports-focused publication. Are fantasy sports not effectively videogames?

We could look at the structures set up by the game hosts, analyzing and dissecting the software they have developed to help manage and run games. We could look at the organization of the leagues, a feat of collaborative gaming that rivals the most involved of Dungeons & Dragons campaigns. We could try to understand how fantasy sports challenge the notion of bounded play, the idea that we set our play apart from our regular life, often an essential formalist argument about games.

Am I playing fantasy football as I sit down to watch the games, keeping track of my team? Where does playing end and spectating begin? Indeed, there is much that can be learned and interrogated about fantasy sports.

Maybe there is not enough audience overlap for the “gamer” population game criticism attempts to serve, though I doubt it. I’ve made my point before about the need to pay closer attention to sports videogames like Madden or NBA2K, titles that have far more in common with a game like XCOM or even Fez than fantasy sports (although the former, with its careful resource management, has more than a bit in common with fantasy sports), and so maybe it should come as no surprise that fantasy sports are not covered with any regularity.

It might be enough to say that looking closely at fantasy sports will not only enlighten us to their impressive systemic complexity. Furthermore we would gain valuable insight into the other types of games we play, by holding them up in comparison. Whether considering interface design or cooperatively managed systems, a closer examination of fantasy sports offers a lot to the broader domain of games criticism and thought. The boundaries of gamer culture, and the hierarchies of distinction separating games are rapidly eroding. Videogames are all around us, on our phones, on our urinals, and on our Facebook feeds. We must continue to open our minds up to different kinds of videogames, especially when so many choose to spend many hours, days, months, years, and in my case, over a decade playing them.