In the May 2007 issue of Computer Gaming World, columnist Jeff Green wrote an enthusiastic preview for a role-playing game by Danish developer Braak Studios called Cudgel of Xanthor. The game had everything: waterfalls, swords, über-realistic sound effects. But there was one problem—neither the studio nor the game existed. “It was a case study in (purposely) bad writing,” Green explained to me by email. He had hoped to make a point about lazy games journalism—or games—that leaned on endless cliché. The result surprised him. “When [the preview] was published, it was astonishing how many people—even knowing they were reading my backpage column—thought it was a straight preview.”

The off-handed stab at creation presaged a coming shift in responsibilities. After over a decade and a half of writing about games, Green wanted to help make them. He joined Electronic Arts in 2008 as a producer and writer for entries in the popular Sims franchise. Two years later, he became Director of Editorial and Social Media for PopCap Games, creator of Plants vs. Zombies, Peggle, and the upcoming Solitaire Blitz. In four years Green went from poking fun at the industry to helping shape one of the largest and most successful social-games publishers on the planet.

They say everyone’s a critic. And in our Tweeting, Tumbling present-day, the adage may well be true. But not everyone’s a creator. Green’s dual membership offers up a privileged view at how the written word shapes the games we play. I caught up with Green over email after just missing him at PAX East in Boston over Easter weekend. After I offered a time to meet up, he texted me in apology: “I might be wandering w zombies by then…”

/ / /

During the “Gaming for Grown-Ups” panel at PAX East, Ken Levine said it’s a shame people let go of what they loved as children. What did you read growing up? And how well have you remained connected to your youthful passions?

I read all the time as a kid and basically have never stopped. I have to give the standard boring nerd answer and tell you that my first big love was the Lord of The Rings trilogy, which I discovered in the fourth grade. I carried that thing around like scripture. Other than that, I was not a big sci-fi/fantasy geek as a boy. I gravitated more toward mysteries on the one hand, and then humor on the other. I had a subscription to MAD magazine during its glory days (about 1968-75) and used to dream of writing for them.

I basically never “grew up” in some ways because I never understood what that meant. Why would I stop liking comic books or Alfred Hitchcock movies or the Three Stooges or the Clash? I didn’t have a lobotomy or personality transplant.

The first game you ever played was Zork. Text adventures seemed like the inevitable merging of literature with interactivity. Why do you think they went away, at least as viable commercial products?

[Text adventures] were mostly just a product of their times. They went away because, as we know, most people would rather look at things than read things. I think we can safely acknowledge this. We played text adventures because there weren’t graphics-based games yet. Once even the crudest graphics-oriented games became available, it was all over. Some of the text adventures were near-works of genius, thanks to the talents of some truly smart, funny folks, like Steve Meretzky, who were perfecting the form as they were inventing it. But for the most part, we want to be entertained. We’re looking for distraction and escape and we want the creators to do it for us.

I know that’s how I feel when I want to read. I don’t want Philip Roth to cede control of one of his narratives to me. He’s a better writer and storyteller than me by a magnitude of one billion. I want to follow where he’s going. And really, we weren’t “reading” text adventures per se. I sat down to a text adventure in 1980 the way I’d sit down to Skyrim now—to challenge myself. Not to experience a narrative. Both are active experiences, of course, but one is a matter of receiving entertainment, and the other is a matter of exercising certain mental skills in a challenging format.

Many modern games emulate film. Is there a reason for games to try borrowing from books instead? Does PopCap look for mediums outside of gaming, like literature, for inspiration or ideas?

I really hate that so many modern games emulate films. Very few can get it right. The classic example of over-hype to me was Grand Theft Auto IV, which so much of the gaming press was splooging over [upon its release] as some kind of milestone in storytelling (one particularly embarrassing train wreck of a review compared it to Steinbeck and Twain, if you can believe it), when, in fact, it was just standard-issue gangster stuff that dozens of movies have done better in the last three decades alone.

If I were actually a game designer and not just a blabbermouth who talked about games, I’d love to look into telling a story the way, say Haruki Murakami does it—something surreal and suspenseful and funny. There is no question that “outside” ideas inform design. It’s why, when I was a magazine editor, I used to constantly have to tell prospective young writers/editors that playing games all day long and being good at them was not enough. Not nearly. It’s just too limited of a worldview. That’s why it’s no surprise at all when you talk to the greatest, most visionary game developers—guys like Shigeru Miyamoto, Will Wright, Ken Levine—they always mention influences that are not only outside gaming, they’re outside of all popular entertainment; fields like architecture, mathematics, philosophy, ecology.

The way games should borrow from books is simply the way any creative types work: to examine the forms you love, the influences that affect you emotionally and intellectually, and find ways to incorporate it into your own work. The best games to me—the most “artistic” ones—are always those that stand on their own as pure games, without pretending to be something else. Pac-Man is basically perfect in this way.

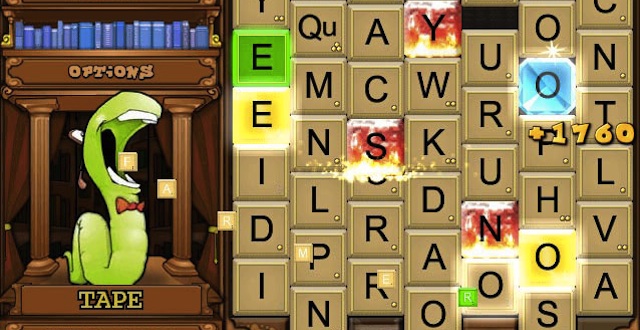

PopCap’s Bookworm is one of the few successful word videogames. Very few even attempt it. Why do you think Bookworm works, and is fun, when so many others fail?

Well, for one thing, it’s actually a videogame, as opposed to just a translation of a boardgame. That is, it uses videogame conventions—power-ups, sound, music, and those infernal burning tiles—to keep you engaged on a level beyond that of just a digital crossword puzzle. There’s an element of tension throughout. I also think—and Boggle has this as well, to be fair—that there’s something about the layout of the letters that always makes you feel like there just have to be better, bigger words in there if you just look hard enough. And that desire to do better just stays with you every game.

There’s also the matter of Lex [a cartoon worm that eats your played words], who may seem like just a silly “mascot,” but in fact adds a level of personality that most word games don’t bother with. So I think Bookworm succeeds [because] you engage with it the way you engage with other videogames, rather than with other word games.

During the “Gaming for Grown-ups” panel, you said that today’s gaming landscape is so much better than it once was, primarily because of a greater sense of connection to other players. But are there risks that such an always-on climate might take away the immersive, solo experience of playing … the way we sink into a good book?

It’s not like you’re forced into the always-on climate, are you? I put over 100 hours into Skyrim. That was all me-time. I didn’t even really talk about my experience much with others. And even in some online games, you can play by yourself. I recently got back into World of Warcraft because I wanted to see more of the Cataclysm zones. So I created a new character on a new server and didn’t tell anyone, specifically because I didn’t want to get back into a group experience again in that game. So, really, you can be as much of a shut-in and hermit as you want to be.

The difference between now and when I was growing up was that many of us didn’t have the opportunity to connect with other gamers even if we wanted to. Back then, this kind of pastime was far less accepted than it is now. There are folks in my own family who are as far from any nerd culture as you can get, and yet they still know what Settlers of Catan is and like to play it. In the early ’70s I’d buy an Avalon Hill boardgame, set up all the pieces, and then just imagine playing it with others. That sounds kind of pathetic, I know, but I didn’t know any better.

Games are finally being made for all demographics. Other forms of media have long embraced a wider audience. And some of this is accomplished through different genre for different people. So: If PopCap was a genre of book, which would it be?

Oh, gosh. Certainly not Romance. Or Horror (zombies notwithstanding). So I don’t know. Popular Fiction? General Audience? Basically a big umbrella. A lighthearted book for everyone. Like a Calvin and Hobbes anthology.

You said as you age, “you stop trying to be … you stop trying.” Basically, there’s less incentive to feel cool. Less embarrasses you. That being said—anything in literature or games that you feel a bit of shame in enjoying?

The only time I felt a twinge of that recently was while reading The Hunger Games on the Kindle. Which, you know, was pretty good in a potboiler sort of way. I do still sometimes balk, while on flights, at reading the digital comics on my iPad. I can’t help but feeling that the person next to me is looking at me like I have a drool bib on. But in general, I like what I like and I don’t really give a shit what anyone else thinks.

A few months ago I attended the Girl Talk concert in Seattle, which was essentially a rave. I freaking loved it and danced my aging butt off. Afterwards, some young guy came up to me and said something like, “Wow, man, I just gotta say it was so cool to see an old dude like you dancing like that!” It annoyed me for half a moment, but then made me laugh. Because—whatever. There’s no age limit on enjoying the stuff you like, despite what certain desperate-to-be-cool youngsters say.

When you get older you realize that basically nobody is cool. We’re all just trying to figure shit out every day and rarely succeeding at it. I mean, it’s also good to kind of “know your place” a little and not make a complete fool out of yourself. Like you’re never going to catch me in skinny jeans at age 50. (And even if I tried, my daughter would see to it that it didn’t happen.) But in general, nah. You can laugh at me for playing Pokémon or Skylanders. Life’s far too short for me to care.

PopCap’s new game, Solitaire Blitz, is a digital version of a card game. We’re seeing this more and more, with boardgames being adapted into iPad games, etc. In the book industry, eReaders are exploding in popularity while major booksellers are going bankrupt. This was your daughter’s first convention. What would you rather survive for your grandchildren—physical books, or physical games?

Personally, I never thought I’d switch to the Kindle. I thought I’d be the very last guy. (Ironically, my daughter herself is quite the Luddite. When we’re reading together on the couch, she says my Kindle “doesn’t count” as a book.) But, as with music, the ease and accessibility of digital books eventually won me over. Because I travel so much and read so much, it’s just a no-brainer for me to have a Kindle over a pile of books. And, contrary to what I used to think, in the end, it’s the author’s thoughts and language that matter most—not the medium.

But with physical games, you are actually talking about an in-person interactivity with other people. The boards, the pieces, the cards, all of that is part of the group experience of playing. My kid and I could pass the iPad back and forth to play Carcassonne at home, but it’s not nearly the same thing and I don’t think it ever will be. Sometimes it’s just nice not to have a screen in front of you.

You began as a games writer. Where should writing about/for games go from here? How would you like to see games journalists cover the industry, now that you’re on the other side?

I feel like we’re at the beginning of a nice mini-renaissance of game writing. There are a lot of younger writers and newer sites that have a fresh approach and attitude that I like, and I think it’s partially because you guys have grown up with this stuff. It’s an ingrained part of the culture now, and so you can dig in intellectually on the subject matter rather than wasting so much time just trying to justify it or defend it or make it measure up to more “legit” forms of entertainment. So what I’d like to see is less navel gazing and more big-picture stories.

I’d also like to see—and maybe this is my biggest wish of all—a more independent press. A press that wasn’t afraid to ask hard questions and depend on PR departments to spoon-feed them stories and information. So much of the power is in the hands of the publishers to dole out information. If you don’t play along, you often get denied access. But in the big scheme of things no one benefits from that. Not even—with all due respect to my bosses—the publishers, even if in the short run they think they do. But with a press that was truly independent, you’d get more of the type of articles that the whole industry needs, in which shit can get called out, bluffs can be called, misinformation can be challenged.

I remember a while back being amazed by the Twitter feed of the Hollywood Reporter’s Tim Goodman as he was live-tweeting a weeklong TV event with all the networks. He was just fearless in his pronouncements. And, as far as I know, no one at CBS, NBC, ABC or anywhere else blackballed him. This is what we need more of in games journalism. Smart and fearless writers who speak their minds—and an industry that’s mature and confident enough to let them do it without repercussion.

Image from Bookworm