“The sequel no one asked for,” begins one user review of Uriel’s Chasm 2: את on Steam. It’s a solid thumbs-down verdict and it sums up the general sentiment surrounding the sequel to one of Steam’s most hated games.

Uriel’s Chasm has around 2,500 user reviews and not even a fifth of them are positive (that is, giving the game a thumbs-up). This leaves it with a rare “Overwhelmingly Negative” verdict. In the Steam forums for Uriel’s Chasm 2 one person asks its creator, straight up, “what in the world would possess you to create a part 2?” It’s a good question.

“something darkly rebellious and destructively psychedelic”

Dylan Barry, the Welsh creator of Uriel’s Chasm, admits that he was never going to make anything ‘normal’. He turned to micro-game development after being a failed musician and busker (you can listen to his newer songs here). Indie Game: The Movie was the catalyst. Barry saw in that movie people describing the games they were making as a musician would the songs they had written—something intensely personal. It opened his eyes to the potential of making his own videogames.

“I had no idea people were writing games like songs these days,” Barry told me. “I’ve been writing songs since I was about 16 and to me this was like a whole new palette of emotion.”

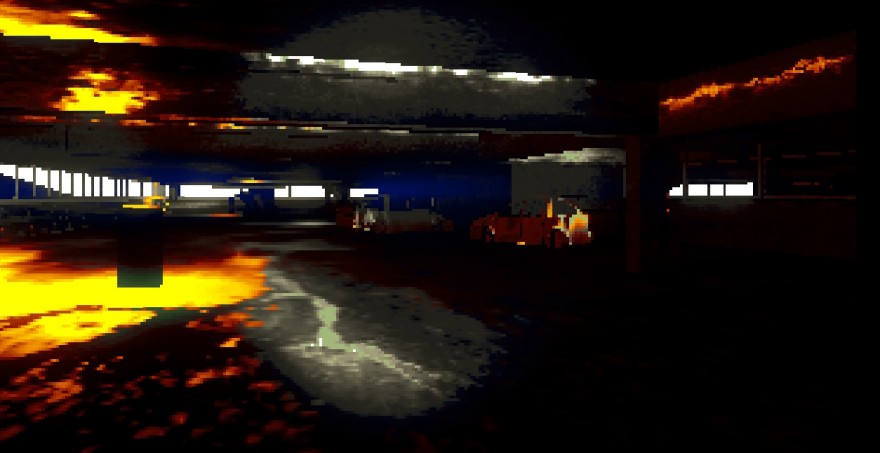

What Barry saw in Indie Game: The Movie is likely different to what you or I did as he was coming to it without any prior knowledge of the subject. After his viewing, he saw the word “indie” as meaning “something darkly rebellious and destructively psychedelic,” and he fully planned to use that understanding of it as a launch pad. In truth, the movie wasn’t Barry’s first contact with the world of videogames. He had, in fact, happened across a few games on the Amstrad back in 1988, and instantly fell in love with how surreal they were. He points to the black skies the games back then often had due to the technical limitations, placing entire levels inside voids. One game he picks out is Spindizzy—the hard-edged 1986 action-puzzler—for its use of color to discern ice and desert levels, yet still hung them against that black sky.

These games captured Barry’s imagination but, more than that, he says they caused a religious awakening in him: “I remember the time I accidentally put a magnet up to my monitor and it was like the apes finding the obelisk in 2001: A Space Odyssey. I wept bitterly all night, not able to revert back to the blackness, first time I ever prayed to the God I would later follow.” If you haven’t tried it yourself (and you probably shouldn’t, by the way) putting a magnet up to an older computer monitor dramatically transforms it into a conductor of the psychedelic.

After that night, Barry tried to hack out artistic games on his Amstrad BASIC, but soon became frustrated at his lack of technical know-how. He remarks that with this frustration came a certain attitude that he hasn’t let go. When making games with the more accessible development tools of today, Barry channels his younger self, inspired by the lyrical worlds that he imagines when listening to the songs of Swans and Soundgarden. “Polish or popular conventions don’t usually come into it,” Barry says. “Originality was always my reason for everything, I will 100 percent go down with this ship.”

It’s this attitude that has led to the creation of Barry’s games. You can see in them quite clearly the hallmark of ’80s shmups, and his love of Codemasters quattro packs, as well as the mini-game laden film licensed titles of 30 years ago. But Barry mixes this with another big part of his life as a born-again Christian. Nearly all of his games feature religious themes, referring to parts of the bible in their stories, or challenging players to restore their faith. “I’m not really making Christian games but I love some of the interpretive techniques the Apostles used to unwrap the Old Testament,” Barry says. “Greek metaphysics and typology.” The result of all this is a baffling concoction of references to the Nephilim and outer-space demon monstrosities, all wrapped in up a shovelware aesthetic.

Barry didn’t realize that bringing these games to Steam would seemingly offend so many people. He saw in their reaction a familiar “religious behaviour,” as if he had walked into their temple and smashed their stone commandments, which laid out what games were and how they should be. Small details such as not having an Options menu was enough for some to scream bloody murder. It was for aspects such as this, along with its esoteric narrative and peculiar challenges, that Uriel’s Chasm was labeled “bundleware” by its many new players after 2500 copies of it were given away for free as part of various promotions. But Barry wore this label as a badge of honor. This is exactly what he was going for. “My aim was to potentially change a person’s life with something made for mass bundling,” he tells me. “I wanted to play right into the pigeon hole I’d been put in, then feel around for the walls, the limitations of exactly what could be achieved in that dark place.”

This was an aim that had emerged in Barry since people had read much deeper into his first game (//N.P.P.D. RUSH//- The milk of Ultraviolet, which he describes simply as an “action game with organ trafficking”) than he could have expected. They traded passion poems and odd interpretative stories with each other after their time with the game. Seeing this, Barry decided to make games for these people, and these people alone. Fuck what anyone else thought. This is why he has since gone out of his way to create a loosely connected universe for his games to be united within. Settings from one game bleeds into another as grainy VHS footage, cults and their devilish rituals spun furiously into a tangled web of meta-fiction meant to encourage you to join the dots. Barry was particularly inspired by the Five Nights At Freddy’s series of horror games—which his eight-year-old son is infatuated with—and how its creator Scott Cawthon had found the fun of stringing its community along with deliberately obtuse lore.

Putting all of this together inside his games has been a journey of self-discovery for Barry. He’s piled on pounds and then lost it all by surviving on a diet of fruit. He left church due to theological issues and grew increasingly paranoid (most of this happening during the development of Selfie: Sisters of the Amniotic Lens). He’s pushed through these dark times and continued creating. And now, with Uriel’s Chasm 2 being his latest creation—stylized as a ROM hack and “multi-genre Love story”—he says it’s the “deepest” of his yet. “It’s heavily encrypted with all kinds of things, relating to other games and also themes such as the garden of Eden, Cain and Abel’s sacrifices, Satan, the 16-year-old me on BASIC, and the fruit is actually subconsciously put in there because of the huge lifestyle changes I had to make,” Barry says.

It’s so personal as to be convoluted. But if just one person can find something in Uriel’s Chasm 2 that changes their life even slightly then Dylan Barry will be satisfied.

You can purchase Uriel’s Chasm 2: את on Steam.