Before playing Wii Party U, Sara needs to make her Mii. Ten years ago this was a sentence written by ESL students. Six years ago it whiffed of voodoo, of the new. Today it’s a matter of course, a ritual that is understood and near-forgotten.

It’s easy to ignore how important and just damned charming the whole process is. She takes a photo of herself with the Wii U GamePad and watches as her real self transmogrifies into a Mii cartoon avatar. Upon the reveal she cracks up, horrified at her likeness staring back at her, but amused, the way we enjoy seeing a sidewalk artist’s caricature exaggerate our biggest flaws. There she is, up there on the screen. Now we are ready to play.

Nintendo has always reveled in cheap magic. Their “Wii” series of games, rekindled on the Wii U for the first time with Wii Party U, demonstrate talents first honed before they even made videogames. More than any other franchise, Nintendo’s games starring cartoon versions of their own players tap into the same kind of experience offered by their initial forays into entertainment.

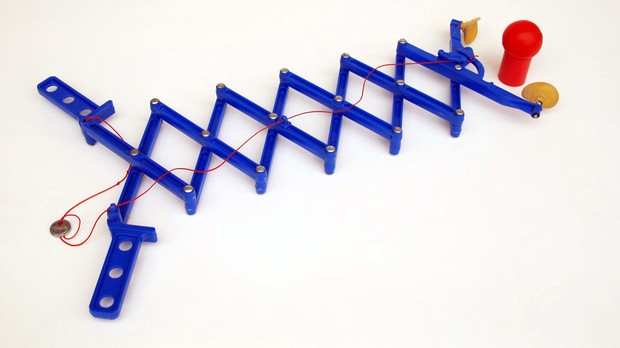

One such dalliance was the Ultra Hand. This was a simple toy made by Gunpei Yokoi in 1966. By using criss-crossing levers and a plastic handle, Yokoi designed a simple grabbing tool that was fun to use. Squeeze the handle and watch the hand extend outward, like some makeshift cyborg. Travel fifty years into the future; swinging a racquet in Wii Sports for the first time held the same instant appeal. And the reason any ripple made by the Wii six long years ago turned into the tidal wave it did is that nobody was turned away. Anyone can swing their arms. Anyone can grip and squeeze a handle. And so they will, if properly enticed.

Videogames have incubated for so long under their own isolated heat tank that the very playing of them requires mastery; to play presumes having played before. First-person shooters have acquired a necessary motor skill language obvious to long-time players but utterly baffling to the new. MMOs and MOBAs are mechanically simple, comprising the same mouse-clicks we perform a thousand times a day, but demand the ability to parse a dense forest of on-screen visual cues indecipherable to the ill-informed. (Not to mention their very genres are obscured by insider acronyms.) These are enormous hurdles to overcome for those joining the playing ranks of today’s most popular types of games. With Wii Party U, Nintendo continues their efforts begun over half a century ago to include, not exclude, the majority.

. . .

The game is played by playing other, smaller games. Ah, the dreaded genre: “Mini-game collection.” This is a pejorative term to most. There is a stink to the phrase, made pungent by dozens of quick cash-ins made to capitalize on fads and passing fancies. But Nintendo hasn’t veered. Instead they own the term. They embrace its possibilities. Already they’ve released two such compilations during the Wii U’s first year: Nintendo Land and Game & Wario. Each are scattered with ideas, but each are also grounded in videogame logic and rules. Wii Party U boils down interaction into the simplest inputs: Press A; Look closely; Move your arm; Read someone’s mind.

Each mini-game is a single idea executed clearly. Most take less than thirty seconds. By themselves, they come and go, forgotten quickly. But compiled and played with others, they become something else: Tiny platforms on which to stand or fall. You’re cheered or booed, cursed out or rooted on. Their simplicity masks their challenge. Anyone can press a single button. But can you watch an elaborate maze of falling dominoes, keeping track of how many blue tiles fall and pressing the button for each? I thought I could.

Most of these games are framed around a boardgame-type set up. But others exist as separate knick-knacks, a quaint interlude while others are off doing something else. With the GamePad’s built-in screen, a series of tabletop games are played solely on the controller; the retail package even comes with a small plastic stand that helps the Pad lie flat.

The games themselves—foosball, curling, baseball, and others—are designed as modern-day mechanical toys. They react as if tangible. Button presses don’t make a little man jump; instead, the press might flip a peg upwards, propelling a silver ball up a ramp, as in Tabletop Gauntlet. For these games you and another player stand or sit at either end of the GamePad like you would a physical object. Play is detached from the TV; it’s just you, your opponent, and the playfield between you. The dual sticks on the controller become knobs on a parlor game.

Tabletop Baseball is particularly brilliant, a simple Pitch-and-Bat game whose field resembles electro-mechanical games of the early 70s. Fielders are roaming holes on the ground; land the ball into predesignated divots for extra-base hits. Score a run and the view shifts to your Mii standing over the table, the same one you hover over.

Though a tiny attraction among near one hundred, Baseball shows us how today’s Nintendo is few steps removed from their past; the game itself is a pseudo-copy of one of the company’s other pre-videogame toys, the Ultra Machine, an automatic whiffle ball pitching device sold overseas as the Slugger Mate. Both exemplify how a game, if good enough, can still be engaging when stripped bare. And how the presence of others remains a necessary part of Nintendo’s design strategy.

. . .

The horizontal graph showed three cartoon heads dropped on a single line, ranging from ‘Not At All’ to ‘Very.’ I had to select, in secret, how I thought of myself, with others in the room guessing how I’d respond. The results were up. My wife’s Mii landed close to the middle. Her friend was a bit more optimistic, edging slightly to the right of center. My own bearded avatar appeared far from the others, a few ticks from the very edge.

“What!” My wife expressed something between a laugh and a cough. I worried she might be choking on something. It was my ego. “You’re not that mature!” she said.

What began as a simple question-and-answer game soon escalated into the same bellows, retorts, and exclamations found on 24-hour news channels. She stared at me in mock horror. I shot my hands out to the side, palms skyward, as if begging forgiveness, but also challenging her to prove otherwise.

Wii Party U’s “House Party” modes ditch most gamey conventions and land closer to Charades. Do U Know Mii is the game that most resembles The Newlywed Game, and so it’s the one most likely to instigate full-on living room warfare. You’re asked questions while others vy to guess your answers correctly on a sliding scale. Some are more emotionally loaded than others. (Acrophobia is hard to begrudge.) But what works so well here is that most of the action takes place beyond the software’s edges, the same way a boardgame need only supply some cardboard, movable pieces, and a goal: The people in the room take care of the rest.

It was getting late. Time for one more. Name That Face sounded provocative, a nursery rhyme for disembodied heads. My wife took the GamePad; only she saw the request, the face we were soon to name. She snapped a photo of herself. Soon the image came up on the TV. Her lips were drawn down, the after-effect of swallowing something putrid. Her eyes squinted. She looked in pain, or confused, or sick. Four options came up. “The color blue!” “The color red!” “The color green!” The color yellow!” She had molded her face into a hue. These were nonsense riddles, the same under-the-blanket questions kids entertain themselves with while the parents drink too much gin. We stop asking these questions once we know they don’t have answers, when we realize they don’t mean anything. But what if they do?

My wife’s friend plugs in her answer, I do the same. The answer: The Color Yellow! Her friend was right. They excitedly exchange a blow-by-blow of their shared thinking: how each of the colors had an obvious facial equivalent (sad, angry, etc.) but Yellow had none, and so her face exhibited this confusion, the feeling of not knowing your place. My wife carved despair out of downcast eyebrows and wriggling lips. Because she was yellow. Of course she was! I’d had no idea. But this was only Round One. We sat on the couch, voices rising, and played, looking each other in the eyes.

Ultra Hand Image from Eric V