Balatro and the expected value of wonder

When I was in college, my fraternity took an optional group trip to Las Vegas that I did not enjoy. A friend's father, who apparently gambled quite a bit, had racked up some points for hotel rooms. If we could get ourselves to Las Vegas, we could stay the weekend for free. What should be a prompt for a wild college weekend instead created constant stress for me as a non-gambler.

To start, I had little money—about 70 dollars for the weekend—and keeping enough to be able to buy food on the plane flight home was my own little game. I foolishly believed playing penny slots would open the doors to free alcohol (it does not), and there's not really anything to do on the Strip for free. Robbed of inebriety, drenched in frugality, it was a lackluster weekend.

Since then, I've never really been interested in gambling, so when Balatro was released earlier this year, I reluctantly jumped in.

Balatro is visually straightforward. It's poker, but with a strong helping of collectible card games like Magic: The Gathering. You get a hand of cards, can augment them in all kinds of outrageous ways, and shoot to top a score target each round. It's also a "roguelike," meaning the hands and drops change every single time you play it.

The big innovation for Balatro was playing with the Joker, a card that generally does not appear in poker like Texas Hold 'Em. Balatro's Jokers are imbued with all types of quasi-magical powers that range from the simple (The Juggler increases your hand size by 1) to the arcane (The Obelisk reads "X0.2 Mult per consecutive hand played without playing your most played poker hand." Ok, what?). The Jokers are received randomly and/or can be purchased one at a time. For people who like systems-heavy games, the mix of the simple (a deck of cards) with the complex (150 different Jokers) is catnip. There are only 91 rules for a chess game, but there are more possible outcomes than the stars in the sky. Balatro possibilities surely extend to the multiverse.

That said, I did not particularly enjoy Balatro. I've played enough games to know when something is not for me, but in the process of digging for hints, I was deeply curious about the intense interest of players. Balatro seemed to unlock something primal in players who compared diabolically complex strategies to legendary bouts of luck. It was a type of enjoyment that was utterly foreign to me.

That others are interested in something that I am not is something that interests me. So what is it about a game like Balatro that triggers ecstasy in some and revulsion in others? Let's look at the appeal in two ways: the system and the aesthetics.

In poker, the lengths people will go to improve their potential success and winnings is well-documented. In a review of consummate gambler and occasional forcaster Nate Silver's book, Idrees Kahloon writes about his self-improvement regimen to increase his odds at the table:

The effort to improve one’s rationality as a gambler easily approaches the irrational. Even my own study of poker became moderately obsessive. I watched hours of poker-strategy videos and long montages of televised poker tournaments with commentary; I went through the lecture notes of a class taught at M.I.T. called Poker Theory and Analytics. Learning about pot odds—it turns out that you can confidently meet an opponent’s call with positive expected value (that is, money-making on average) if your chance of winning is greater than the share of the pot you’d be contributing—made me understand where I’d erred."

This sounds like work, and both Kahloon and Silver acknowledge that in some sense, poker the game and poker the practice are a profound waste of time.

Although poker is an arena that prizes decision-making, most pros would [...] be better served financially doing something else for a living. Clearly, its rewards aren’t fully reflected in the +EV models.

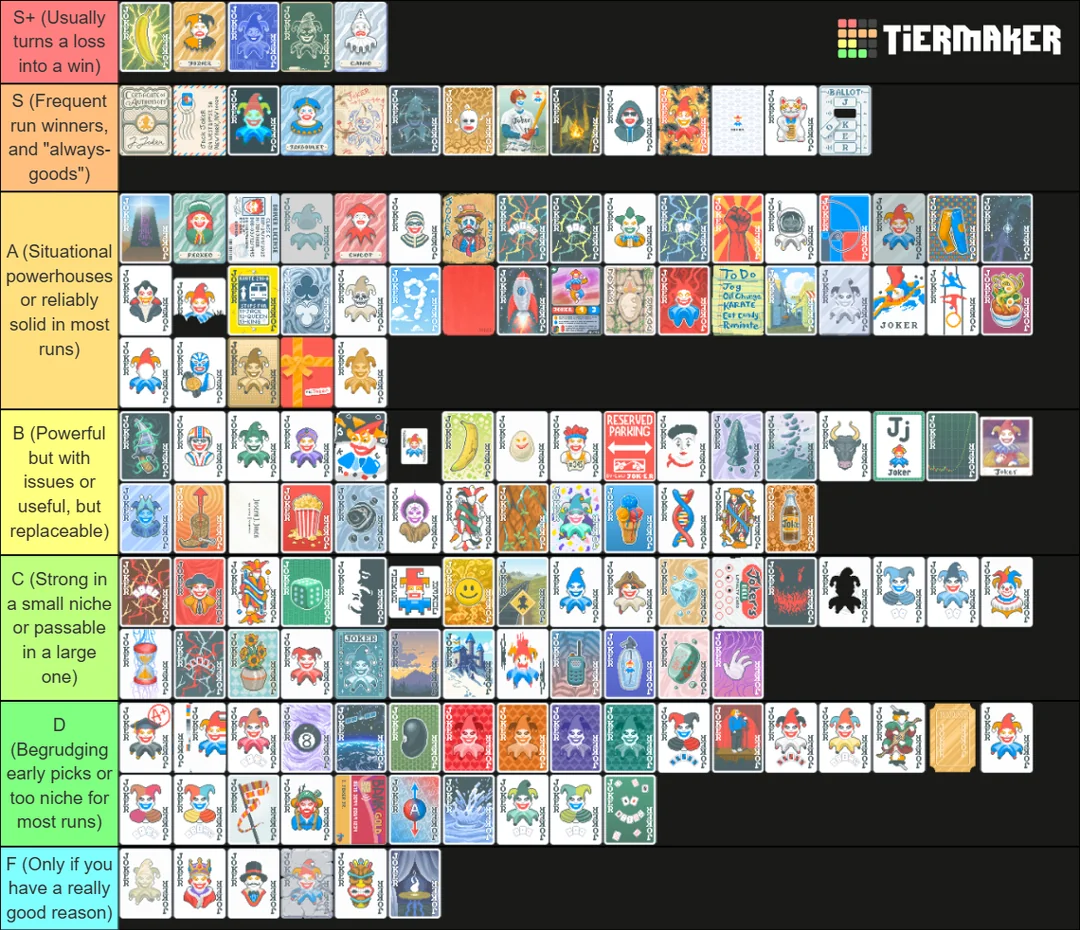

In Balatro, similar attempts at optimal strategies dot the pages of Reddit and elsewhere. People share the "seeds" for successful runs so that others can reproduce their game. (It's similar to sharing the exact starting measurements for a recipe, recognizing that the craft is in the tacit knowledge needed to construct the dish.) Others refer to "tier lists" to determine which Jokers provide the most value with specific strategies in mind.

It's worth noting that talking about Balatro has in some ways become a more critical social function than playing the game itself, given that the game is a solitary pursuit. More importantly, discussing Balatro creates more distance between the game and the player. The goal is not a good time or a desirable hand. It's some distant, unknown future of ludic purity.

But the joys of mathematical systems only beget more mathematical systems. In both games, math meets more math as "solver" programs now demystify the unknown and provide the most profitable recommendations for how to play a poker hand. Likewise, you can now play a practice Balatro game on GitHub, hand by hand, card by card, to try to fully optimize a score. You'll never regret another decision again.

Where does this leave you as a player, though? After creating the first poker solver program, Oleg Stroumov reflected, "This journey made me realize my true passion lies in developing complex programs rather than playing poker." On the one hand, everyone should find their truth. On the other hand, diving deeper into a game would lead you out of games entirely is suboptimal for the medium. Like poker, Balatro raises a central tension: when optimization becomes so naked and onerous, does joy disappear?

Solver programs like GTO Wizard make the math of poker strategy easier to learn.

Balatro hasn't appealed to me partly because I'm not a natural optimizer (although I am a Virgo!) in my play. I try to build systems to keep my structure documented in real life, but that patience evaporates when I encounter a game system that requires it. Balatro is a perfect game for those who've succumbed to the "optimization sinkhole" in the words of Anne Helen Petersen:

I also believe that we’ve collectively become very good at mistaking the feelings of optimization, organization, and control for fun. Organizing your fridge is not fun. Neither is watching someone do it. It is satisfying, and it is satisfying because it offers a flicker of control amidst the natural and amplified chaos of our lives.

The optimizing, maximin approach to the play of complex systems, I could never quite get. There must be a beauty that transcends a score or a pot size.

Another way to think about "easy to play, hard to master" games like poker is to consider how they trigger challenge as sensation. Balatro cleverly uses the appearance and iconography of poker to disguise a more complex strategy game. One of the key ways it does this is through a compelling string of design decisions that create an allure from the mundane. The flicker of the faux CRT display. The undulating background. The slot machine ring of a combo. The casino's alchemic elements transmute the cold calculus of victory into limbic ecstasy. This is the aesthetic of calculation without the culture of the casino.

Conversely, Silver and other commentators of poker describe the human elements that make the risk of poker desirable. The thrill of risking your own money. Bluffing and strategy. The workings of the human mind at a poker table. It's not the game rules of poker that excite players; it's the extracurricular elements that draw comparison to narcotic use. "The dopamine rush that follows a successful bet will trump the slow-burning satisfaction of contributing to your Roth I.R.A.," Kahloon writes again. But again, Balatro isn't real, so what gives?

At this point, we are no longer talking about games. We are talking about the sublime, about simulation. The enjoyment from Balatro is the enjoyment of preparation and execution unmoored from the casino. It's for valuing the tedious setup of hundreds of dominoes in an afternoon over watching them fall. By contrast, to many other games that provide moment-to-moment activity, the enjoyment is the negative space when a player seems to be doing nothing at all.

And perhaps that's something I can only experience second-hand. To wit, this:

Every Red Seal Steel King held in Hand has the following:

• 4 X1.5 Mult abilities: Steel + Baron + Brainstorm + Brainstorm

• 4 retriggers: Base Trigger + Red Seal + Mime + Blueprint

This gives 4x4 = 16 X1.5 Mult calculations, which is X1.5^16 = X656.8 for each card.

I use 54 Cryptids, which gives 1 + 54*2 = 109 cards. This means a mult of X656.8^109 = X1.2e307.

With the non-steel Red Seal King we get another X1.5^12 = X129.7, which puts us beyond X1.7e308 = 2^1024, which is the largest number represented by the double-precision floating-point format used by Lua in the LÖVE framework, which Balatro is programmed in.

Due to implementation details, it results in a "nan" value before the "e" and a "inf" after it, so we get a score of "naneinf".

Becomes this:

Earlier this month, I spoke with Risa Puno who uses simple games like mini golf to expose deep emotional realities. Balatro engages in the same pursuit. We are surrounded by the beauty of math every day, in the shape of leaves, a sunrise, bird song–but perhaps to feel that complexity, it takes a whirr of a virtual casino bell. It's opaque, arcane, and truly remarkable.

In an optimized world, perhaps the most radical thing is to make optimization beautiful rather than efficient.