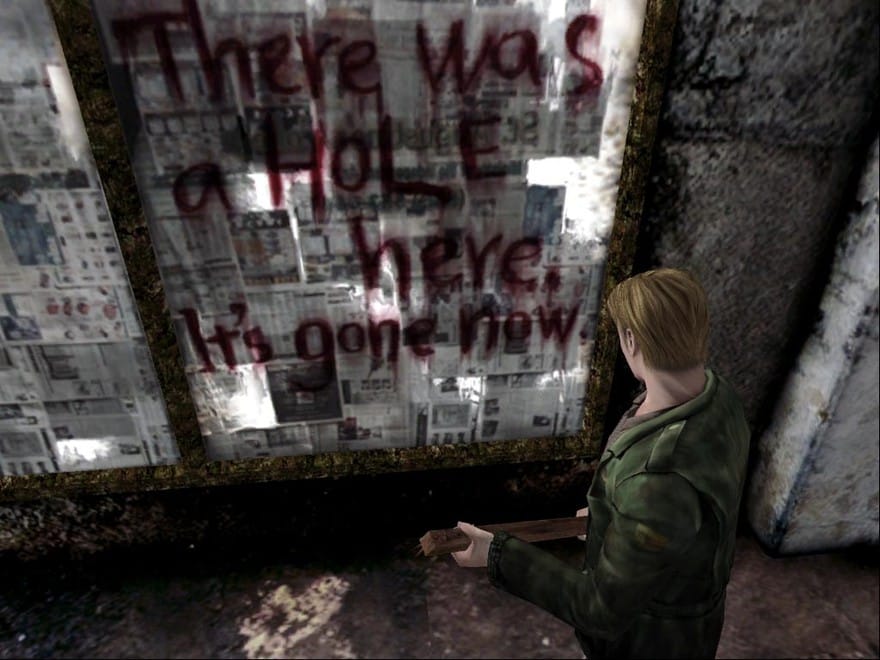

Silent Hill 2’s architecture, along with its iconic blend of fog and darkness, is its main antagonist. Returning to the game after all these years, it’s surprising to find that its enemies are barely a threat, its puzzles mostly “lock and key” affairs and its bosses require a single tactic—point and shoot. But navigating its dim hallways, cramped rooms and sprawling titular town can be a challenging affair. Overlooking a detail in the dark, forgetting to check a door, even missing the map for an area, forcing you to go by memory—these are the game’s central struggles. Perhaps this is due to the ambiguous nature of much of the game’s environments: There are more locked doors than open ones, more dead-ends than ways ahead. Sometimes it almost feels like poor level design, especially when you find yourself in a corridor of 10 locked cells, rattling each handle as you go. But there is sense behind this system, if not sanity—this is videogame architecture that is as unhinged as its broken doors.

Oddly enough, this unnerving dysfunction stems from the game’s sense of order. It has an obsession with the well-ordered spaces of institutions, taking the player from an apartment block, to a hospital, to a prison, and finally a hotel. The symmetrical ground plans for these locations, found on the game’s various maps, seems to have been pulled wholesale from life, rather than created for use in a videogame. In order to become functional spaces in a game where exploration is key, these maps have then been hacked into, with entrances blocked off and walls smashed through. The divisions, functions and even internal logic of the game’s architecture is subverted, room by room. The game constantly forces the player to turn back on herself at a dead end, to check again and again the map, and try to connect its straight and true lines with the decaying masonry around them.

This is videogame architecture that is as unhinged as its broken doors.

Spatial orders are more than just matters of logic and function. The design of a prison or a hospital is as much an exercise in ideology as it is a case of putting things where they need to go. This is a distinction that Silent Hill 2 more than acknowledges. Yet it is not simply the horizontal orders of numbered rooms and lengthy passages that mark out the architecture of Silent Hill 2 as distinct—it is also its obsession with the order of verticality.

///

“Verticality is ensured by the polarity of cellar and attic, the marks of which are so deep that, in a way, they open up two very different perspectives for a phenomenology of the imagination. Indeed, it is possible, almost without commentary, to oppose the rationality of the roof to the irrationality of the cellar.”

- The Poetics of Space

, Gaston Bachelard

///

The descents of Silent Hill 2 are many. It is no coincidence that the game’s protagonist, James Sunderland, begins his journey at a rest stop high above the town, and must descend into it. This marks a preoccupation with downward gestures that recurs throughout the game, from elevator rides, to climbing into your own grave. The logic this is based on is one that we intrinsically understand—the marks of this system being, as Bachelard says, “so deep.” The order of above and below is a classical one, marked by the concept of the “underworld” in ancient cultures. Thousands of years of heaven above our heads and hell beneath our feet mean that “going down” can never be a positive gesture, and descents are often in fear or madness, rather than safety or comfort. When Dante begins his long descent into Hell in Inferno, he simply states, “I entered on the deep and savage way.” This line stands alone amongst the rhyming triplets that make up this work of classical verse as an ominous sign.

Silent Hill 2, being a game, plays with this idea in an almost sadistic fashion. Again and again it beckons players into deeper and deeper spaces, such as the “basement’s basement” that lies beneath the hospital. On the staircase on the way down, a cry can be heard, something between a dying animal and the call of a satanic child. At the bottom of the stairs the player must push aside a bookcase to reveal a small crawl space behind, leading down into darkness. The choice to descend is a tense one, but the result is a fairly well lit and tiny room, with little more than a bloodstain and a metal ring. It’s a red-herring of sorts, a trick to give the player a false sense of security before the real descent begins.

///

The Shepard tones were discovered by Roger N. Shepard in 1964. A series of looping “pitchless” tones that overlap, they create the effect of a constantly ascending or descending sound. Shepard was a psychologist, and this illusion wasn’t created as a compositional tool or a trick, instead it was as part of an experiment into how the human mind perceives sound. If you listen to a descending Shepard tone for any length of time, the feeling of being slowly dragged down, almost compressed, is unmistakable. It’s that downward movement, the slow decay of a sound. How far can it continue? You ask yourself, how much deeper? But the tone is steady, its slow descent both rapidly falling and yet going nowhere at all.

///

In the final third of Silent Hill 2 the player arrives at the top of a staircase. Its not the first staircase in the game, or even the last, but it is the beginning of something. Projecting down into darkness, it marks the start of the game’s most exhausting descent. Over the next few hours the player will pass down ladders, stairs, wells and holes, each one descending into darkness, and each one revealing another level, another strata of the descent. It’s a dizzying experience, erasing any sense of reference the player might have for how deep they are.

Much like Shepard’s looping tones, the truth is, of course, that beyond the first staircase, the player never descends any further. The many plunges into open black holes are simply transitions between levels, sinister versions of Mario’s warp pipes. This is little consolation for the player though, as every encounter with another one of these gaping pits brings a sinking feeling of depression. Another one? you ask, before hesitantly leaping in.

It’s during this descent that Silent Hill 2 begins to display its consideration of architecture. Hundreds of metres beneath the town, its hard to see the game’s spaces as plucked from real life any more, and they soon take on a more symbolic nature. This one long descent is symbolic of the game’s thematic descent into both history and memory. Like Dante’s encounter with figures of classical and ancient history in his journey, the player encounters revision of the characters they encountered earlier in the game, now locked in the grip of obsession and terror. They form depth markers on this slow downward slide, each one portrayed as a victim of their basest psychological urges, their unrestricted desires and fears allowed to run rampant. This is where Silent Hill 2’s architecture reveals itself as a psychological construct. Up above, in the town, ordered spaces stand in a struggle with the onset of decay, but here, as you tread ever deeper, the subconscious takes over.

///

“The mind is like an iceberg, it floats with one-seventh of its bulk above water.”

- Sigmund Freud

///

Freud’s topographical model of the psyche is one of his most influential ideas. In it he proposes that the mind can be thought of as having a “depth.” The peak of this depth is the conscious self, the Freudian “ego.” This is the location of identity, which is judged and controlled by the critical “super-ego.” But beneath both, lies the subconscious, or the “id”—the location of desire, impulse, covered over by a layer of memory and knowledge. This topography, whether you believe in its real-life application or not, is the key to understanding the architecture of Silent Hill 2.

When the player descends beneath the town, she passes through these layers. Consider this—the top of the staircase lies within the “Silent Hill Historical Society.” History is a concept entirely under the control of the super-ego, as it is the critical judgment and arrangement of “facts.” In this building the player encounters paintings of the town’s history, with snippets of information. The staircase itself lies through a burnt and shattered wall, a breach in the structure of the building. The descent then passes through a prison, a space which could be considered as the site of conflict between the ego and the id. Being a place where order is maintained, and those who break the rules are kept restrained, it is a clear symbol of the “self-censoring” activity of the ego.

And beneath this? The incoherent labyrinth, huge and irrational in its construction. Here you encounter both James’ desires and those of the other characters. This Freudian reading of Silent Hill 2 is a well-worn one, and has been part of of the game’s history for many years, but it is the implications of this reading, not the reading itself which is important. By seeing Silent Hill 2’s architecture through this lens, it allows for a more sophisticated understanding of how space within games has a potential for the expression of complex concepts. By acknowledging the game’s Freudian approach to level design, it is impossible to continue to read its architecture as a literal expression of a town, or a simple obstacle course. Instead it opens it up to more and more readings and counter-readings, discoveries and enigmas. Silent Hill 2, in its considered and intelligently constructed spaces, still remains a haunting and elegant expression of the possibility of architecture in games.