The Beginner’s Guide to the art of videogames

As an art professor, teaching the relative value of “artist’s intent” is one of the most difficult concepts to unpack. It’s not that artist’s intent is so tricky to comprehend—it’s simply what the artist means to do with a particular work. The difficulty comes from being in a position of both instructor and critic. After all, I, like many of my colleagues, do not hand out good grades for effort, for merely expressing the intent and putting forth the time to produce something worthwhile that may still fail to resonate. Thus, we push our students to learn how to more effectively communicate what they’re trying to say in order to bridge the gap between intent and the actual artwork being exhibited. The catch is that there is no recipe for success, and the most interesting art is often the work that defies conventions of structure and taste. In other words, the difference between clever and misguided, removed from the influence of intent, is often purely a matter of perspective.

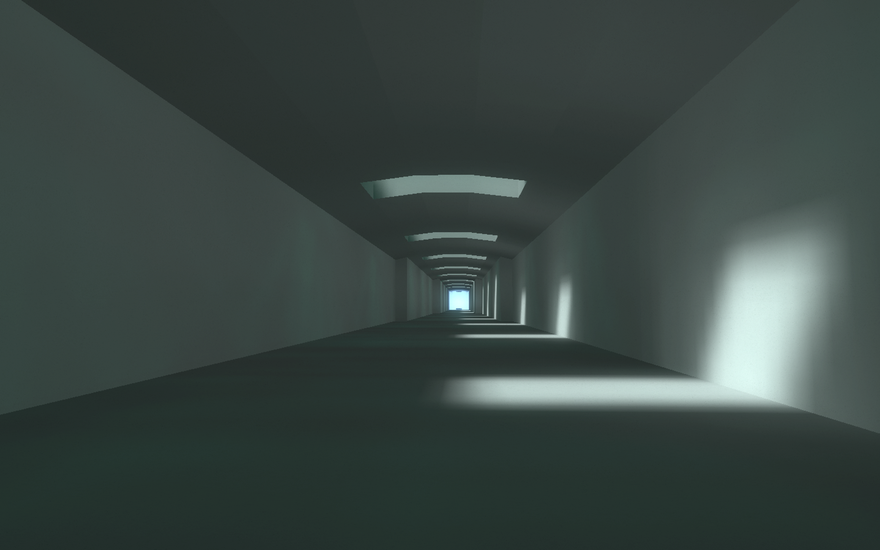

The Beginner’s Guide, the new game from Davey Wreden (co-creator of the postmodern triumph The Stanley Parable), bathes in the turgid circular logic of artist’s intent and authorship. The game is a curated tour of the virtual worlds supposedly made between 2008 and 2011 by a friend of Wreden’s named Coda. Many of these games are brief, somewhat unfinished or broken scenarios where you walk through a space and see what you see. As you play, Wreden offers a “director’s commentary” over the proceedings, presenting critical insights into the underappreciated brilliance of Coda’s creations. Wreden also steps in from time to time to help players past certain time-consuming obstacles such as a prison door that won’t open until you’ve sat in your cell for an hour. The narrator asserts that knowing the intent behind Coda’s artistic moves in such cases is enough to understand them without having to experience them in totality.

Have you finished your tinfoil hat yet?

The game pours on the layers of clouded authorship so thickly that trying to ascribe intent to the in-fiction artistic decisions in The Beginner’s Guide is a fool’s errand. For starters, Coda is most likely a fictional character, which implies the games are IRL Wreden’s creations. But Wreden also plays an in-game character version of himself, muddying the connection between his narration and what he may actually think of these interactive vignettes. Also, The Beginner’s Guide is presented as documentary, making the role of you, the player, to solely take on the role of you as a player, which you’re already doing by playing it. However, Wreden is actually the one steering the ship here, making your role as the player purely instrumental to his own storytelling about what might be the developer and/or the narrator’s own design decisions. Have you finished your tinfoil hat yet?

Throughout The Beginner’s Guide, Wreden repeatedly ascribes artistic intent to the assets and mechanics in Coda’s games, interchanging between acting as critic and tour guide. As we’re taken progressively through the timeline of Coda’s work, Wreden’s interpretations paint a picture of the game maker as an increasingly depressed, disconnected, and vindictive artist. However, the more Wreden intervenes by inserting bridges over invisible mazes and letting players in on secret codes, the more doubt is cast upon the authenticity of Coda’s games as presented. Though this relationship is made somewhat more explicit later on, it’s clear that, to some degree, Coda’s games have been altered beyond the artist’s original intent and perhaps in direct defiance of it. What you believe depends on who you trust.

What makes The Beginner’s Guide different than just another exercise in unreliable narration is how it uses artistic intent as a smokescreen, and amidst the confusion sneaks in a much rawer insight into what creative process and output actually entails. Relatively early on in the game, you play a title I’m going to refer to as “Notes,” where cabbage-sized glowing comment bubbles dot a cavernous system of open, winding pathways. Wreden asserts that even though the core conceit of “Notes” was supposedly that these comments were left by actual players, in truth they were all composed and inserted by Coda. Wreden, in turn, interprets this as a cry for help, positing that Coda is so lonely that he’s invented conversations with make-believe people. But putting Wreden’s potentially deflecting interpretation to the side for a minute, there is one glaring element in “Notes” that Wreden never even mentions: smack dab in the middle of the game there’s a giant, vibrantly colorful, abstract painting.

Wreden never speaks of the painting but the comment balloons do. And for anyone who has tried to talk about art in a mainstream videogame space, the content of the comments is depressingly familiar:

“Whoever made this has issues.”

“PAINTING. WHAT DOES IT MEAN!!”

“I think it’s about how things look messy from up close and perfect from far away.”

“Spoilers: it doesn’t mean anything.”

“It’s about how this game is pretentious and you all suck.”

“art.”

As a player, you’re powerless to change what the bubbles say and unable to contribute your own. All you can do is engage in a mental exercise of critique, an ephemeral process that lasts only as long as your attention span. The painting, an artwork laid bare, is dismissed by the commenters and left hanging by Wreden. The narrator instead sharpens his focus and critical thought on the salaciousness of melodrama and the hidden truths uncovered by “puzzle solving” throughout The Beginner’s Guide. Analyzing a painting is an aimless diversion compared to that goal. And besides, the joyous explosion of colors in the painting probably runs counter to narrator Wreden’s thesis about Coda’s mental state. While the symbolism of the creative process as a prison is beat into players’ heads in so many of the scenarios that follow Notes, the direct inclusion of visual artwork, so symbolic of the cultural status videogames desperately aspire to, is ignored by our adept tour guide.

Later on in the revelatory pre-epilogue chapter, messages from Coda to Wreden are printed onto the walls of a labyrinthine art gallery. There are even little, roped-off stanchions protecting the words from being touched by players, or perhaps Wreden himself. Formally, these messages are reminiscent of the works of conceptual artist Lawrence Weiner. Most relevant to The Beginner’s Guide are Weiner’s “statements” where words and phrases selected by the artist are painted onto gallery walls. These “statements” have been collected by museums around the world and in most cases, no physical artwork actually exchanges hands as part of the acquisitions. Instead, what is “collected” is a loose set of instructions for the artist or museum staff to paint text such as “A RUBBER BALL THROWN ON THE SEA” or “HERE IS IT” on a given surface. Interestingly, when Weiner first developed this process of making, he also formulated what he called a “Declaration of Intent.” That is:

1.

The artist may construct the piece.

2. The piece may be fabricated.

3. The piece need not be built.

The structure Weiner builds for his process is not one where he is able to control how viewers read and interpret his works, but merely presents a set of guidelines to express the artist’s intent for what his works should be. And in The Beginner’s Guide, Wreden pushes players to consider the game developer’s role as a prompter of thought along a similar vein. Narrator Wreden’s interpretations of Coda’s games are limiting and, at times, reaching, but that’s not where the game leaves us as players. Through Wreden’s subsequent unravelling, we’re clued in to the fact that if there’s any “solution” to Coda’s games, it’s that the nature of art is in constant flux, and that looking for truth in art via intent is likely to reveal more about the one looking for it than the original subject. The “story” of The Beginner’s Guide is instrumental; it’s a way of setting up the game pieces and the loaded symbols in a specific arrangement for players to experience and come to their own conclusions.

Yes, The Beginner’s Guide occasionally fumbles its narrative, Wreden sometimes overacts, and the writing can be a little ham-fisted—but the game also provokes incisive, critical thought about the way we read and evaluate games, and does so not by laying out a definitive “message” to be delivered to players, but by prompting us, through play, with open-ended questions. It’s not something that happens very often. I don’t know if that is what Davey Wreden intended, but that’s what I got out of it.