Behind the humor of Toby Fox’s Undertale

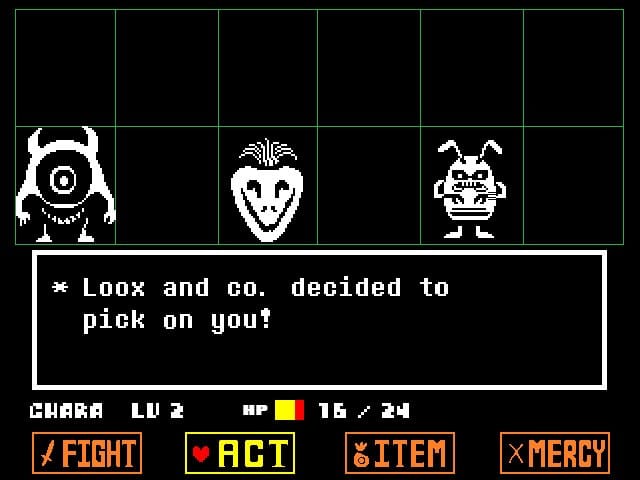

“What’s compelling about EarthBound is that it is not only funny and strange, but also sincere and emotional,” explains the game designer Toby Fox. EarthBound is part of the Mother series, which has left undeniable fingerprints all over Fox’s new game, the subversive role-playing riff Undertale. “It is able to inflict all sorts of different emotions on you, despite looking like a weird off-brand Charlie Brown game,” he said. Like those games, Fox’s creation leans more than a little off-center in every facet: the writing is mostly delectably silly, colored with ridiculous phrases like a frozen “Bisicle” treat that can be eaten twice, or an endearingly misspelled sign that adorns the Snowdin library. The art emulates more than a little of that “weird off-brand Charlie Brown game” look, replete with monsters posing in awkward, physically-impossible “battle stances,” cute dogs that have inexplicably come to inhabit suits of armor, and sprouting lily pads that you carry (how else?) by balancing them on your head.

I asked Fox if the naïve art style was intentional or a budgetary choice “Even if I had a team of 100 artists,” he said, “I probably wouldn’t want it to look any different.” There’s a psychological thread that says audiences become more attached to characters drawn simply rather than in detail, because we can project an image onto it. “Visual gags usually benefit from funny, expressive drawings,” he said. This is similar to the popular JRPG trope of a silent protagonist—a trope which Fox also utilizes. The heightened connection we feel to these characters is part of Fox’s plan to befriend his players before eviscerating them. There are many twists in Undertale, each one knowingly, dramatically built up and then subsequently defused by all manner of comic relief. Gut-wrenching tragedies or heartwarming intimacies can occur, but everything gets coated in Fox’s signature absurdism. All of this adds up to an experience that is, by turns, disarmingly funny and genuinely emotional.

It’s difficult to even name these peculiarities, as knowing what you’re getting yourself into might spoil the sense of wonder that Undertale imparts on new players. The same is true of Fox himself…The direct answers I seek are considered “spoiler” territory. He’ll reveal bits and pieces of what eventually became Undertale’s DNA: the Mother games, Shu Takumi’s games, shmups, Super Mario RPG. But largely, Fox’s world is best understood via discovery, a unique universe with its own internal logic that players must traverse for themselves. “The hardest parts of writing, to me, are the parts that aren’t text,” he told me. “Once a character’s voice and mood is established, writing scenes is pretty easy.” For Fox, expedient world-building comes naturally when that world seems like it is simply expressing itself—the stories are there, waiting to be heard.

Once you’re in there, there’s a sort of logic to it all. It suddenly makes sense that the mysterious Dog Residue item could spawn a useful Dog Salad, or that a late-game heartthrob antagonist thinks humans eat burgers adorned with sequins. These nuances strike first as surreal humor, subtly laying the groundwork for the deeper understanding the game tugs at you to uncover following your first playthrough. Keith Stuart, writing on the identity paradox of game protagonists for The Guardian, asked readers to name videogame characters that they felt connected to. The resultant list included one-dimensional characters like Pac-Man and Cool Spot. Often, the most inscrutable on-screen personalities can come to reflect the hidden, idiosyncratic parts that compose our deeper selves. Sometimes, a mere symbol can impart a closer sense of familiarity than the most verbosely developed character.

Fox’s world is best understood via discovery

Certainly, a filmmaker like David Lynch is no stranger to using inchoate or obtuse symbolism to hint at a more complex metanarrative, and Undertale definitely contains its fair share of Lynchian horror—a distinct, often unsettling blend of the familiar and absurd. I’m thinking here of a specific late-game act only accessible after beating Undertale once, a haunted area full of worryingly vague monster amalgamations and veiled psychic disturbances. The kicker, of course, is when a companion shows up to shoo the foes away—these abominations are simply antsy from not being fed. This act is kick-started when some friendly bonding draws the player into a tense scenario, which is subsequently diffused at peak horror by—you guessed it—goofy witticisms. This delicate push-pull happens again and again in Fox’s work, but never feels canned or tiring. Just as a Lynch scene can pull together the disparate ends of fear and farce, often becoming nauseatingly dissociative along the way, a similar thread of unnerving direness moves silently below the surface of Undertale. It’s a game that draws you close to its secrets with an unassuming sheen of friendliness, piecing out the disturbing bits between bigger bites of humor so it’s easier to swallow.

Fox might disagree with such analysis. “It’s just ‘Toby Humor,’” he says of his style. Of course it is. Fox doesn’t need to explain himself or wear his heart on his sleeve—the game does it for him.