Behind These Walls

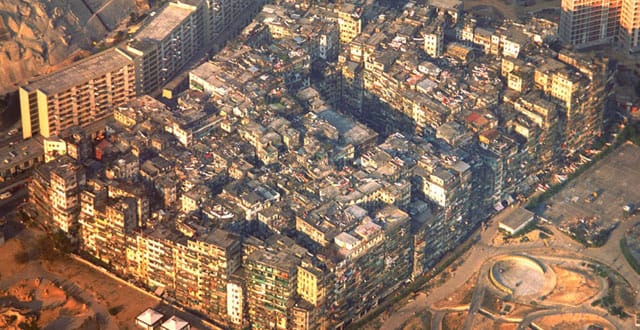

Architects and designers once hailed Kowloon Walled City as the closest thing to a self-regulating, self-sustaining modern city that had ever been built. If the high-rise was supposed to be the prerogative of Modernism, it was simultaneously disconcerting and fascinating to architects that a skyscraper city could be built by the masses. Claimed by both Hong Kong and China but administered by neither, Kowloon Walled City also became a dystopian breeding ground for illegal activity—opium dens, brothels, gambling houses, unlicensed medical clinics, and a thriving drug trade run by mafia syndicates. Even the police were afraid to go inside except in battalions larger than 40.

Kowloon was built on a 19th-century Chinese fort that was surrounded by the British colony of Hong Kong. The British launched a military attack to seize this 6 1/2-acre enclave. But when they arrived, they discovered that the Chinese soldiers had left under their noses. The British did nothing with the city afterwards, nor did the Chinese reassert control, leaving the place to its own devices. By the 1930s, the Walled City had become a symbol for a declining Old China, surpassed by the modern infrastructure around it.

The population of the city grew from 10,000 in 1971 to more than 35,000 by the late 1980s, but the borders were fixed. With nowhere to go but up and nobody to regulate, the architecture was constructed ad-hoc without official building codes. And when it was demolished in 1993, Kowloon Walled City became a true no-man’s land, existing only in our mind’s eye. According to David Grahame Shane, author of Recombinant Urbanism, “The Walled City thus entered [our] living rooms … branded as a doomed, negative, heterotopic element employed for the service of fantasy or illusion.”

You’re outdoors, but the light level isn’t far from being indoors.

It is not surprising that this urban patch has made its way into popular representation: in films, from The Bourne Supremacy to Baraka and Batman Begins; and in videogames, including Call of Duty: Black Ops, Hitman, Kowloon’s Gate, Shenmue II, and Stranglehold. Often, aspects of Kowloon’s architecture and environment are used to impart a sense of repression, confusion, or loss. In videogames, the mafia and undercurrent of illicit activity provided ideal storylines amidst dank and mysterious backdrops. The cramped businesses in the inner alleys, and the jumbled exteriors of Kowloon, gave videogame designers a rich visual vocabulary.

The characteristic that most set Kowloon Walled City apart from other slums was its high-rise, skyscraper form. Videogame design has capitalized on the city’s verticality. In the opening sequence of Shenmue II, we are transported between the normalized architecture of Hong Kong to Kowloon and enter the city as if falling upside-down from the sky into the depths of the Walled City. The distance between Hong Kong proper and Kowloon is greatly exaggerated with hills and wide plains separating the two, likely an attempt to emphasize Kowloon’s “Otherness.”

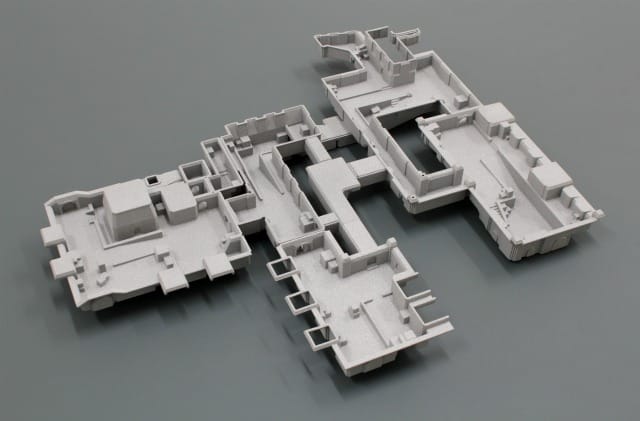

Kowloon was an anomaly in modern urban construction not only for its organic formation, but also for its reversal of standard building aspects: interior versus exterior, street versus roofs. Its ad-hoc construction engendered a maze of narrow alleys and staircases. Think of single apartment units being stacked over time like Jenga pieces—except that the façades don’t have to be match or be in-line with each other. The network was so vast that it was possible to cross from one side of the city to another without touching the ground once. In essence, the roads were on the roofs and inside the buildings.

The “Kowloon” map in Call of Duty: Black Ops takes advantage of this reversal of streets and roofs by focusing all play on the upper levels of the city. A common experience by players when first playing the map is, “Where the hell am I?” A video from DailyMotion goes through the space: “Obviously,” narrator Kevin Kelly says, “This map takes a little bit of time to learn.” Without streets, you traverse over planks, ramps, ladders, rooftops; there’s even a zip-line to take you to the other side of the map. Each building has multiple entrances and levels, and there are many opportunities to fall. At the same time, however, the irregularity of the architecture creates vantage spots for snipers, and nooks in which to hide.

Black Ops also takes advantage of Kowloon’s reversal of interiors and exteriors. Exposed infrastructure and the tangle of electrical wiring are a central feature, looping over the rooftops and continuing onto the ceilings of apartments. Death by falling is compounded by hitting a mess of electrical wiring and signage. Further disorientation is created through environmental effects—man-made in the form of steam, and natural in the form of rain. You’re outdoors, but the light level isn’t far from being indoors.

The cult hit Kowloon’s Gate for the PlayStation locates play down in the depths of Kowloon’s alleyways. The dark colors, steam, and claustrophobic architecture lend themselves to the game’s mythical and macabre characters. In the opening sequence, you go down a series of hallway and doorways that appear to be warping. Kowloon’s Gate reflects the variety of activities within the hallways, including dental clinics, food stalls, bars, and mysterious interior shops. In one scene, a man has been killed and hangs entangled within the electrical wires.

It is because Kowloon was both real and anomalous that it has captured the imagination of videogame designers. The space lends itself to both highly realistic rendering, as in Black Ops; and mythical spaces, as in Kowloon’s Gate. The real Kowloon City was a place beyond the reach of government regulation until its demolition before the handover of Hong Kong. Perhaps it is only fitting that John Woo’s Stranglehold shows Kowloon destroyed not by the hands of Big Brother, but by the inhabitants themselves, in a continuously crumbling space vulnerable to collapse by Triad gang warfare.

Today, however, Kowloon is a modern urban hub with mixed-use skyscrapers geared toward tourism and lifestyle. One player comments, “I have apparently been to the wrong places when I have been in Kowloon. I have mostly seen people shopping and dining; no ballerinas or mechanical cows whatsoever.” Will the Kowloon Walled City continue to inspire game designers and players alike, and will anybody remember that it was once a very real place?