The best ’90s-era Bruce Willis movie is a baffling videogame you never played

This article is part of PS1 Week, a full week celebrating the original PlayStation. To see the other articles, go here.

///

The action hero is an appealing archetype due to its blending of two related fantasies: the fantasy of power, and the fantasy of having carte blanche to unleash that power. From foundational films like Rambo: First Blood to recent insta-classics like John Wick, the essence of the American action movie is a cool, nearly invincible protagonist—most often depicted by a white man in his 30s or 40s—who is given a good reason to kick some ass. The best examples of the genre are unapologetically indulgent of desires for control and justified rage; they are entertaining, mainstream outlets for the core Freudian energies of sex and aggression. This can rub up against the values of a modern, progressive society, and the action movies of a given decade have tended to reflect the cultural pressures of that time.

The 1980s, for instance, were a bastion for the bombastic hypermasculinity of the action flick. Backlash against what was seen as the previous decades’ failed attempts at harmonious peace and love laid the groundwork for some of the most iconic artworks about men who solve their problems by fucking killing everyone. Entries by the likes of Schwarzenegger and Stallone revelled in their excesses and celebrated their stars’ glistening, cut-from-stone physiques. It was an era of supermen packing uzis.

Sentiments shifted in the ‘90s, which brought disillusionment with the power-lust and barely suppressed homicidal rage that had been so dominant in the filmic landscape of the ‘80s. The U.S. was that much further away from the horrors of the Vietnam War, living in relative peace and prosperity, and leaving its young citizenry—especially those belonging to the privileged, dominant culture of young white men—insecure about their right to be so angry. The good vibes of the ‘60s and ‘70s and the megalomania of the ‘80s were now both passe, making the most rebellious form of expression a full retreat from sexual or aggressive passion into ironic detachment. In order to survive, the action movie aesthetic needed to assimilate the self-conscious paradoxes of an ascending Generation X, for which coolness was uncool, genuineness was fake, and disinterest was authentic.

The tried-and-true formula of action movies featuring perfect white male specimens became saddled with embarrassment for its homogeneity and earnestness, not to mention its latent homoeroticism that the average action movie fan was unprepared to own. For a star to thrive in this changing environment, he would have to be the grungy, sarcastic offshoot of those who came before; someone who could uphold the action hero fantasy without making those watching feel guilty about enjoying themselves. He would still be white, male, and virtually invincible—but just not so damn excited about it.

Enter Bruce Willis. Remember classic, mid-1990s Bruce Willis? Back before The Sixth Sense—which marked the start of his incongruous “sad and quiet” phase—when his oeuvre was an appealing mix of surliness, humor, and an icicle to the brain. Back before he was a cool, bald star, and instead was, improbably, a much cooler, balding superstar. Willis came to represent the quintessential ‘90s action hero, exemplifying the mix of privilege, confusion, and irony that dominated the U.S. cultural personality toward the end of the millenium. His most enduring character, John McClane of the Die Hard series, was constantly mumbling under his breath about how annoying it was to find himself in yet another life-and-death gunfight with a bunch of deranged terrorists. By the third film, McClane was an apathetic, alcoholic bum who still managed to take down a network of genius villains, all while battling his true antagonist: a bad hangover.

His oeuvre was an appealing mix of surliness, humor, and an icicle to the brain.

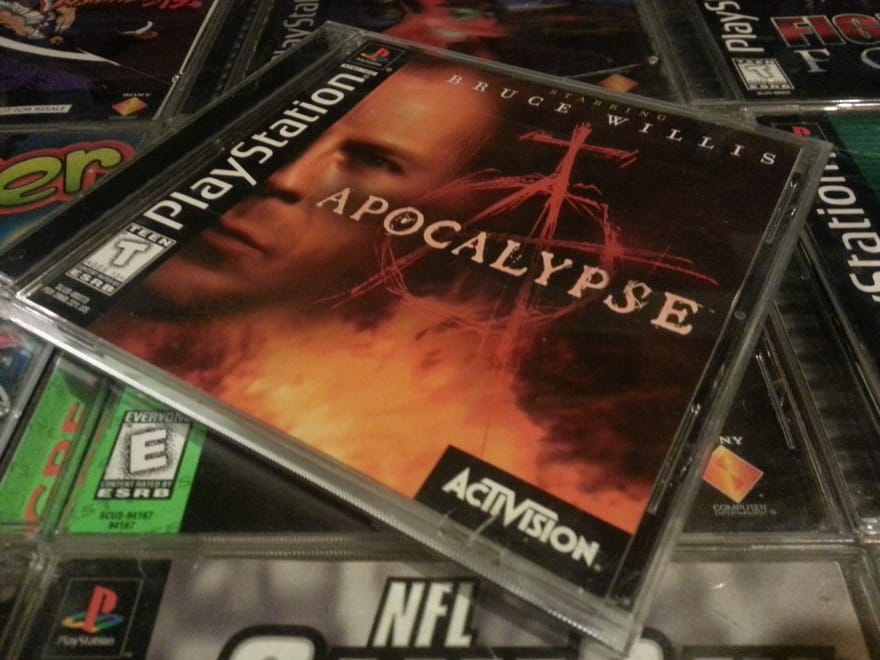

Here was a hero for a generation disconnected from the immediacy of war and strife, and which felt self-conscious expressing strong feelings about anything. Willis repeatedly played a schlep who didn’t know what was going on, didn’t much care, but nevertheless had to clean up everyone else’s mess. He permitted his fans to get revved up, to get angry, to care, precisely because he didn’t; he was dragged into everything with a roll of the eyes and a smart-alecky comment. And though his films have made a lasting mark on the culture, it is in fact a forgotten videogame that boasts the purest expression of ‘90s Willisian fantasy. I am speaking, of course, about the beautiful disaster that was Neversoft’s 1998 third-person shooter for the PlayStation, Apocalypse.

///

In early 1998, the small and unproven development studio Neversoft was about to go out of business. Their brief life had featured one unremarkable release in ‘95 (Skeleton Warriors), one port in ‘97 (Shiny’s MDK), and one cancelled project (alternately known as Big Guns and Exodus) that had absorbed all of the company’s remaining wiggle room. Eleventh-hour rescue came in the form of publishing giant Activision, who recruited Neversoft to resurrect a shelved project called Apocalypse, featuring the voice and “digital likeness” of one Bruce Willis.

Neversoft had developed a robust 3D engine for their cancelled game which allowed them to quickly begin work on this new project. (That engine would next be adapted for the studio’s titanic 1999 hit, Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater.) The core gameplay of Apocalypse is a third-person “dual stick” shooter, in which the left stick of the PlayStation’s then-new DualShock controller was used to move the player character, and the right stick was pressed in the direction the player wanted to shoot. This set-up offered a revolutionary level of precision for a console shooter, giving players a profound sense of command over the virtual action hero. (While Sony Computer Entertainment Japan’s Ape Escape is typically credited as the first game designed specifically for use with the DualShock, Apocalypse’s North American release predated it by over six months—though it should be noted that Apocalypse did not require the DualShock; players could shoot left, right, or straight by pressing the original PlayStation controller’s square, circle, or triangle buttons, respectively.)

Photo of Neversoft employees ca. 1998, courtesy Factumquintus via Wikimedia Commons

As far as I could discern in researching the game’s development, no one at Neversoft ever met Mr. Willis. He had long since recorded his dialogue and signed over rights to texture-map his face (he performed no motion capture) back when Activision had tried and failed to develop the game internally. The original design had cast Willis’ character, Trey Kincaid, as the player character’s wise-cracking sidekick. When Neversoft took over development, focus group feedback delivered what, to us, should be an unsurprising message: We don’t want to play with Bruce Willis, we want to play as Bruce Willis.

Crossing action star with videogame naturally creates the opportunity to take the power/justified rage fantasy to the next level, as we are no longer vicariously watching the carnage but enacting it ourselves. The dual-stick motif was an ingenious way to make the player feel as though she was holding the machine gun (or rocket launcher, or particle beam) while still maintaining a third-person perspective, so as to watch the avatar run, tumble, and weave between bullets—all staples of the action genre. Why anyone thought we wouldn’t want that avatar to be Willis is difficult to fathom. In any case, in order to turn the project around and secure their future as a studio, Neversoft was tasked with a bizarre challenge: turn Apocalypse into an action game starring Bruce Willis, when all the dialogue had already been recorded for an action game co-starring Bruce Willis.

The result is borderline nonsensical. Willis barely speaks throughout the game apart from canned one-liners, and even these often seem to be directed toward a non-existent other. The game opens with a pre-rendered cutscene in which a throaty villain known as “The Reverend” explains that in some vague dystopian future, “religion has become my science.” As we watch him turn on a Frankensteinian machine, animating what looks like bunch of skinless corpses, he explains, “My oldest student, now my sworn enemy, knows my plan, and knows how I raised my horsemen from the dead!” Presumably he is talking about Willis, though none of this is ever explained or expanded upon; it is pure pretext to help us ignore how little sense everything else is going to make. The Reverend proceeds to introduce us to his Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, who will naturally be featured in boss fights throughout the game.

“Welcome to paradise,” he says to no one.

Cut to Willis being tossed into a futuristic prison cell. An intimidating cellmate proclaims, “Boy, you’re gonna have some bad dreams tonight.” Willis electrocutes him (or something?), laughs without saying a word, goes over to a wash basin, says “Nanotech enacted” (or something?), and suddenly a massive gun materializes in his hands. He shoots the cell door open. “Welcome to paradise,” he says to no one.

The game then launches us, locked and loaded, into a prison corridor filled with shootable boxes and enemies. Before our first press of the left stick, Willis shouts, “Here we go, chief!” This first level serves as a delightful introduction to the game’s endless barrage of explosions and low-poly gore. At other points, Willis might call out, “Strap one on, it’s time to jam!” or, “These guys need a little more lead in their diet!” When Willis picks up a flamethrower, he asks, “Feel the burn, kid?”

In the absence of any other context, including an even remotely coherent storyline, we are ultimately left to assume that we, the players, are “chief,” we are “kid.” Through the alchemy of publisher missteps, focus-group feedback, and a pressured development timeline for a studio on the brink of closure, Neversoft delivered a game in which Bruce Willis is speaking directly to us. This is what makes Apocalypse the most indelible ‘90s action experience, surpassing even Willis’ classic films. We are in control of the era’s most iconic hero, making him leap around and explode countless aliens (robots? humans dressed in robotic suits?) and superpowered bosses, and yet there is still a need for this unbridled fantasy to be mitigated by an ironic detachment. Willis interrupts his badassery to talk to us through the TV screen, complimenting our performance and chiding our inexperience. “That last step’s a doozy!” he says as we fuck up a bit of platforming and take damage on a long fall. Thanks, Bruno.

///

Image credit: Classic Game Room

Everything in the game is stripped away but the essentials. The plot is so weird and undercooked that the only salient feature that sticks with us is the very title of the game: the apocalypse is happening, and a better reason to (reluctantly) kick ass and save everyone there could not be. There are no relationships between Willis or other characters. Hell, there is barely any dialogue aside from his meta-cracks to an invisible partner, a role now fulfilled by us as players. Even the soundtrack was pitch-perfect for the era: presaging what would be a hallmark of the Tony Hawk franchise, Neversoft recruited songs from several well-known bands for Apocalypse. One contributor was System of a Down, and it is hard to imagine a more apt group for the project—that is, one that greater exemplified the awkward conflict between rebel and sell-out that pervaded “alternative” pop-culture in the mid-‘90s. Apocalypse treads this very line, as well: is it a cool, misshapen masterpiece, or a bad attempt to score some cash off a Hollywood star? If Generation X taught us anything, it is that art can be both. Yes, Apocalypse is a confused, angry, self-aware mess—but so was everyone playing it!

In the final cutscene of the game, The Reverend lies dying on the ground, and imparts some appropriately vague and prophetic words to Willis: “Don’t you know, he who battles the demons is destined to become one? Shoot me…”

“I’ll see you in hell!” Willis retorts, and empties his clip into the now-helpless old man.

Suddenly, Willis is overtaken with glowing light, apparently being possessed by the very horsemen we just spent hours defeating. He stands up, shakes it off. “Thought they had me there for a minute!” he says. Then his eyes begin to glow fiery red, and his voice turns demonic: “Welcome to paradise,” he chortles at the camera, at us.

Yes, Apocalypse is a confused, angry, self-aware mess—but so was everyone playing it!

It is his final dig. Behind the sarcasm and the shrug-okay-I-guess-I’ll-kill-everyone attitude, Willis reminds us that we enjoyed the apocalypse. It felt good blowing shit up. Perhaps, he seems to suggest, there is a deeper rage inside us worth examining, a fire that cannot be quenched by simply pretending not to care …

But before the thought can go any further, the credits roll. Well, no matter. Good game! Or, like, whatever.