Binary Domain and the importance of shooting robots

A third-person shooter in which you destroy thousands of robots using big guns and lots of bullets. That could be a description for both Binary Domain (2012) and Vanquish (2010). They’re both science-fiction and both published by SEGA. And each of them is styled in a way that might be described as “very Japanese.” But where Vanquish quickly gets old, Binary Domain is alive, vibrant, and keeps you hooked until its end. The difference is revealed in the characters. More specifically, it’s found in the cutscenes. As game-makers continue to explore new methods of interactive storytelling, I understand why cutscenes have become, to some extent, non grata. But the cinematics in Binary Domain, as well as pushing forward the game’s smart, swift plot, are short films unto themselves.

In these cutscenes, Binary Domain frames its human characters as precisely that—if this is a game about the differences between men and machines, then the occasional intimate moments shared by Binary Domain’s cast (the flashback to Dan’s childhood is an eminent example) tell that story. Vanquish, by contrast, is uninterested in people. Its climactic twist, whereby your squad leader and even the American president turn traitor, feels cheap and cynical; an ugly plot turn that sacrifices the game’s humanistic theme for traditional espionage intrigue. Up until that point, you’ve fought and died alongside dozens of US Marines, united in a battle against malicious robots and a cyborg antagonist. When the game spins 180 and announces “actually, your comrades have betrayed you,” it’s a glaring and unfortunate inconsistency. This is a notable contrast to how Binary Domain draws clear battle lines between man and robot—sure, they are muddied in the final act, but gracefully so. Whereas Vanquish goes the other direction, implying similarity between humans and robots by revealing that people are just as abhorrent as mass-murdering machines.

in between two loathsome genres of videogame, it finds genuine sophistication

Binary Domain shows itself as a game appreciative of its audience and their ability to identify adolescent cynicism. It suggests that men and robots are united not through shared shortcomings, but universal goodness. The machines, too, have feelings and compassion—when the child Dan destroys a robot we’re lead to believe this was because it was attacking his mother. In fact, Dan lashed out because the robot had failed to protect his mother from his abusive father. Vanquish wants its players to doubt the entire world. Binary Domain, smarter and more mature, finds the goodness in all its characters, and is a more interesting game for it.

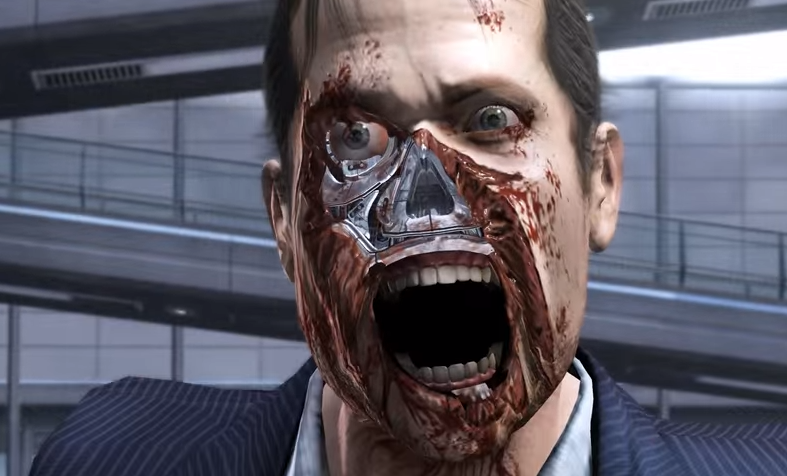

Two other cutscenes deserve honorary mentions: An early scene in The White House situation room is only a few minutes long, but has one of the best twist endings in all games. The human being you least suspect, and who least suspects it himself, is the one who turns out to be the machine. The other scene is the arrival of the Hollow Child robot at Bergen headquarters—the sequence that provides Binary Domain’s most lasting image, of the man with half his face ripped off, revealing circuitry underneath—which wonderfully sets up the game’s emotional through line. With some nasty gore, Binary Domain goes straight for the audience’s stomach and, like Dan, players are instinctively and immediately repulsed by the men-machines. But by the end of the game, to an extent at least, they’ve gone through the same process to gradually understand as the characters under their control. From sharply evoked suspicion and disgust, they’ve grown to like Faye and Cain, the two android characters. Players’ attitudes have matured. It’s another example of the optimism that’s at Binary Domain’s heart: with more exposure to and understanding of the “other,” people’s prejudices will soften. Empathy prevails.

The relationship between Faye and Dan is also lovingly played out. It begins with Dan’s frat boy catcalling, transitions through their sex scene and subsequent fall out, and ends with an embrace plucked straight from ’50s Hollywood. In fact, it puts in mind a simple metric for how to write romance: the two lovers need to have got together, and had sex, before the final act. Anya and B.J. do this in Wolfenstein: The New Order (2014). It helps them seem not as characters that are in love only in a vague, theoretical sense, but people that have a physical, biological attraction to one another. This type of romance also eliminates one of the most awful tropes of the male power fantasy: the idea that the woman is a kind of reward for the man once he has completed his mission. In Binary Domain, Faye isn’t a prize for Dan (or the player) after he’s saved the world. Simply because they’ve slept together, and experienced some kind of emotional consummation before the game’s end, Dan and Faye’s relationship comes across more meaningful than romances in other shooters—it exists outside the paradigm of typical masculine fantasy, and Faye feels like something more than a status symbol for Dan to acquire. Dan matures, from a gawking bro to a genuine lover. Faye, unlike so many women in videogames, is personable and independent. Though she is literally part machine, she feels more human than most of her entirely biological contemporaries. In these two characters, and their romance, we once again feel Binary Domain’s optimistic attitude regarding human beings.

it’s difficult to keep yourself from grimacing

When was the last time you played a boxed shooter, with AAA production value, that was at least eight hours long and didn’t involve killing a single human being? For me it was Portal 2 (2012), and even that falls more beneath the rubric of puzzle games than of shooters. Binary Domain has you dispatch thousands of enemies, using hundreds of thousands of bullets, and yet your endgame body count is zero: very few other videogames, especially those with a 15 age rating (in the UK), can make that boast. And it is a boast. Referring back to those cutscenes, one thing Binary Domain absolutely understands is consistency of tone. Never too serious, never too daft—at the best of times it’s akin to one of Spielberg’s adventure films, a veritable summer blockbuster of a game, appropriately replete with broad appeal. Throw human enemies into the mix and Binary Domain would become much dirtier. Its electric pace and offhand jokes, instead of entertaining, would seem crass, the way Uncharted, at times, can seem crass.

On the contrary, Amada Corporation’s robots make for terrifying opponents and blasting chunks out of them is as grotesquely satisfying as spilling human blood. In fact, it’s outright violent. They are not people, but when the robots’ heads, legs, and metallic torsos go twirling into the air, ripped from the CPU by your pneumatic drill of an assault rifle, it’s difficult to keep yourself from grimacing. It’s a game of high action and high emotion and brilliant for it. Timidity is boring. Clemency is boring. It’s not CGI gore but the videogames that are satisfied with being safe and genteel that turn my stomach. But at the same time, shooters—especially as of late—have grown so very ugly. Churlishness has become insensitivity, boisterousness sexism and escapism is now complete ignorance. Binary Domain is violent and often adult, but intelligent and graceful nevertheless—in between two loathsome genres of videogame, it finds genuine sophistication.

And that’s much more than can be said about Vanquish, and any other game that doesn’t meaningfully consider the targets it throws at you to shoot. When, in the game’s final act, your enemies become humans—instead of the robots you were tearing apart before—the game barely acknowledges it. You kill them, thoughtlessly, as you had done the machines. The message is once again dishonest, self-loathing, and clear: we are all equally worthless. Vanquish may share its theme and fast action with Binary Domain, but only the latter has enough love for people to not continually and meaninglessly throw them before bullets.