Birthplace of Ossian explores the artificiality of videogame landscapes

The mountainous terrain in Connor Sherlock’s exploration game Birthplace of Ossian isn’t of this world. I don’t mean that rather than being real, it is virtual—its disconnection has many more layers than that.

For starters, its colossal landscape is based on Glen Coe in Scotland, a place that Sherlock has never been but feels connected to through media like Highlander (1986)—he’s actually named after the main character, Connor MacLeod. Sherlock wanted his recreation of Glen Coe to reflect his physical distance from it. “I wanted the space to be as distant an echo of the real thing as I could make it, like a garbled game of telephone,” he told me.

the volcanic rocks tower with stupendous verticality

Upon looking up reference material, Sherlock found that he didn’t need to rely solely on his own distant impressions of the location, as it has been subject to a similar act of detached mimicry before. His discovery was the 18th century Scottish poet James Macpherson, who said that Glen Coe is the birthplace of the mythic bard Ossian, from whom Sherlock’s game gets its name. Macpherson apparently spent a lot of his time translating the original 3rd century poems of Ossian, but it’s believed that’s not entirely true and that the poems are mostly his own writing, guided by older pieces and known oral traditions.

Glencoe, by Hugh William Williams, 1812, via Wikimedia Commons

“Now not only did I have my memories of Highlander, but also early romanticism’s take on 3rd century oral tradition, as well as a whole subgenre of landscape paintings inspired by the Macpherson version,” Sherlock said. “I dug into all these as I made the game, though I haven’t yet read the entirety of Macpherson’s work (which is free online!).”

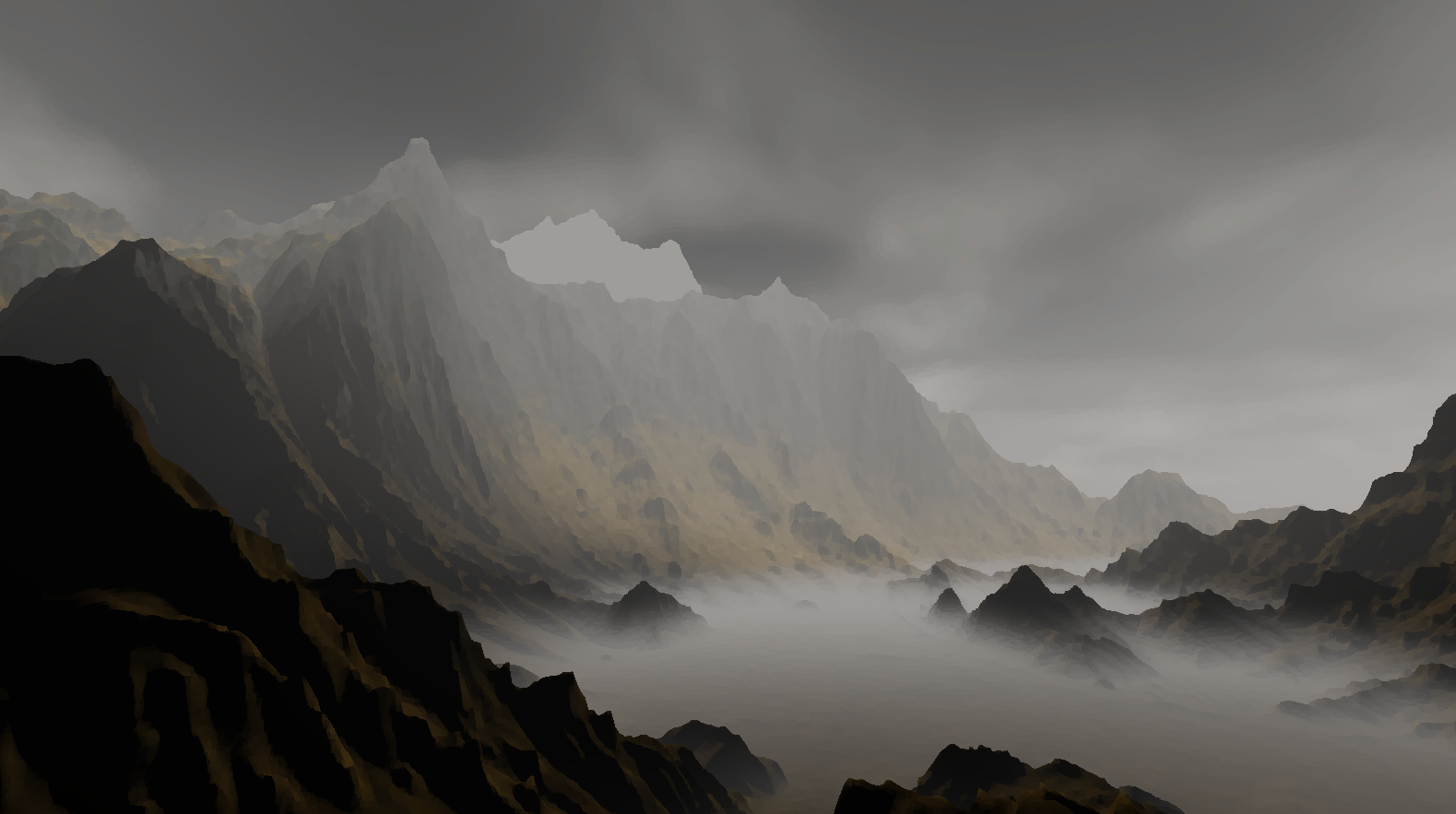

This combination of influences mostly shows in the game through its poetic exaggerations: the volcanic rocks tower with stupendous verticality, while the dips between them are filled with an ethereal fog. There’s also a dreamlike texture to the whole game, as rather than hard details and outlines, the rocks and grass are realized with a watercolor aesthetic. Plus, there are instances of aligned rocks that seem unnatural; either placed there deliberately for some ancient ritual, or are perhaps the knots in the landscape’s tough skin, as if it were a humongous living creature.

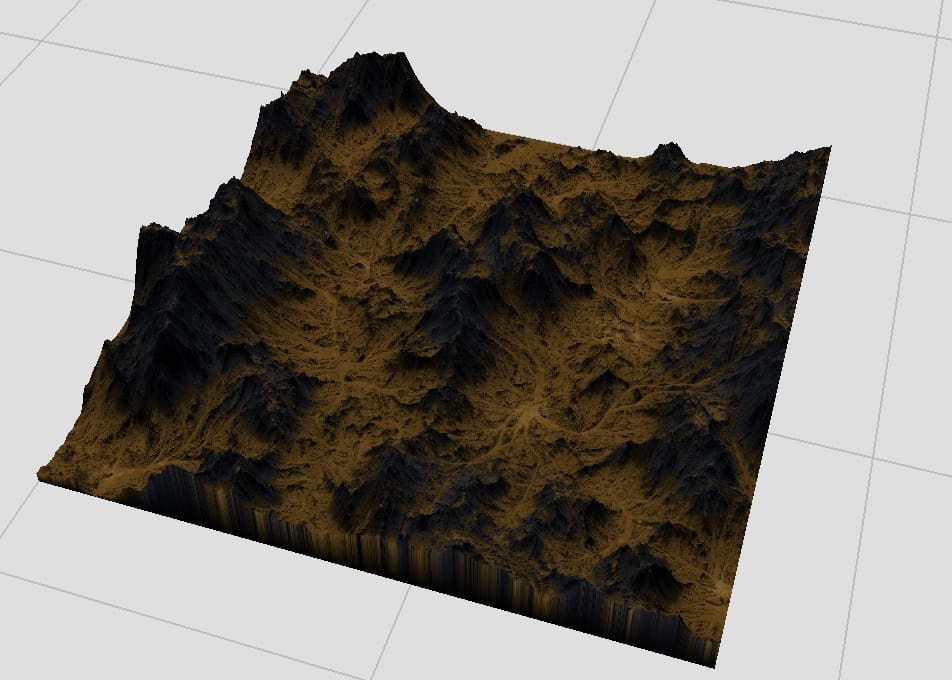

It turns out that most of what you see in Birthplace of Ossian isn’t deliberate or molded into shape by human hands. Sherlock wanted to create “a wilderness that ignores and swallows the player as a real place would,” which required an approach that ignores the presence of the player. He derived the game’s 100km² of craggy land from perlin noise that had extensive erosion modelling applied to it. It took him a number of tries to get it right and when he landed on the look he was after he touched it up as little as possible—no set pieces, no authored sightlines, nothing that would make it more of a playground for the player’s maximum enjoyment, as most other videogame landscapes.

“The result is a topography that can feel hostile to cross unless you choose to follow the ‘ancient’ glacial paths,” Sherlock told me. “But since there’s no win state or ultimate goal (aside from jumping off the edge), I’m happy to have the mountains themselves antagonize the player. Scrambling up hills is a pain in real life, too.”

“By exposing the edge of the world I’m incorporating it into the piece”

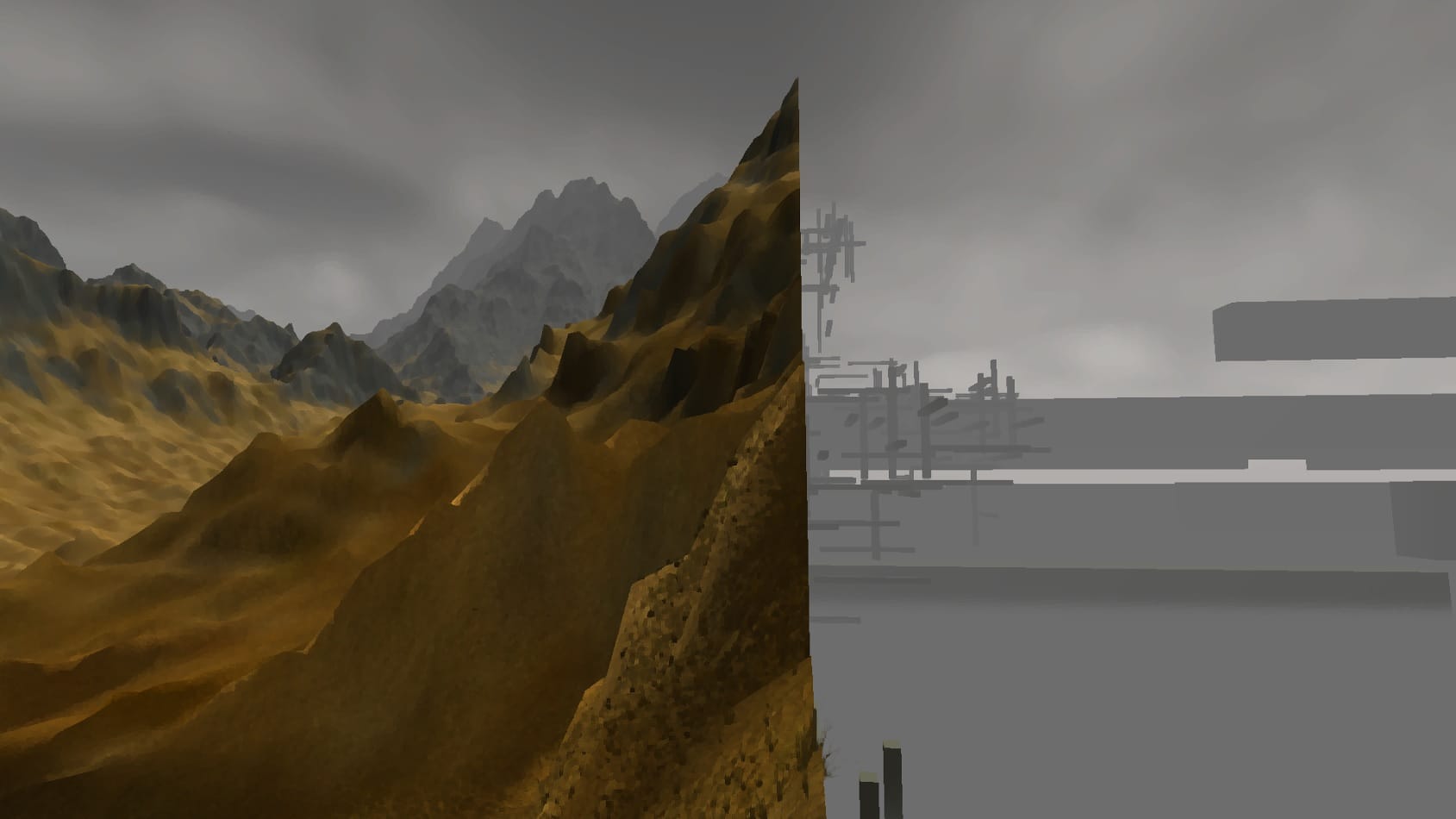

You’ll note that Sherlock mentions that you can jump off the edge of Birthplace of Ossian there. This isn’t a fault with the game but an integral part of it, which Sherlock intended as a way to draw attention to the artificial nature of the virtual space. Most of the landscape’s edges are bordered by insurmountable peaks, but there is an open side that players are encouraged towards by floating structures made of concrete pillars that EW completely out of character when compared to the rest of the game. What they do is indicate the edge of the game world where the voidspace begins.

“The edge of a game world is like the ocean—inhospitable and seemingly infinite,” Sherlock said. “The pillars that extend outwards in Birthplace of Ossian are there to blur the line on where the void begins, and allow the player a vantage point from the other side of it. By exposing the edge of the world I’m incorporating it into the piece, like an elaborate frame on a painting.”

Sherlock is drawn towards this out-of-bounds space due to its “strange power,” which comes from over two decades of videogames trying to hide these empty, black 3D spaces from players. In Birthplace of Ossian you can enter it, falling a great distance, but also finding an unknown realm down there, platforms suspended amid a great fog. It’s as if you’ve accidentally fallen off the edge of Sherlock’s thought cloud which was dreaming of Glen Coe, or exited one of the oil paintings that depict it. Through this, Sherlock asks us to consider themes that surround our lives, such as the constantly shifting line between artificiality and realism, the possibility of heterotopias, and the existentialism of escaping virtual reality.

Birthplace of Ossian is intended as the first in a series of what Sherlock describes as six “semi-abstract, semi-generated pieces of topography floating in an explorable void.” He’s hoping to have them packaged up and ready by the summer of 2017 under the title A Physical Box EP.

You can purchase Birthplace of Ossian over on itch.io.