The Blair Witch Project of videogames comes out September 1st

There was a trilogy of Blair Witch games back in the early 2000s but they missed the point. The 1999 movie worked because it blurred the line between reality and horror. Before the film even came out, the low-key website detailed the fake legend itself and presented its actors as real documentary makers, including photos of them as kids. The website was then updated over time as the documentary was supposedly being filmed. It was shown as going from unremarkably smooth to it all going awry. Over on IMDb, those same ‘documentary makers’ were then suddenly listed as “missing, presumed dead.”

Taking it further, at select screenings, missing person posters were hung nearby to give the idea that The Blair Witch Project was a “found footage” documentary, and not your typical horror movie. The result? When it came out, a lot of people were convinced that the Blair Witch legend was real. And even if they had their doubts, most couldn’t entirely throw themselves in the other direction to outright reject it. The videogames failed to capture any of this because, as with the film’s appalling sequel, they only made painfully obvious the fiction that they toyed with.

But what else could be done? How can a videogame hope to match what The Blair Witch Project achieved? I think Aaron Oldenburg may have discovered the answer. On September 1st, his documentary game 1000 Heads Among the Trees will be coming out. It was previously known as “Cachiche,” which is where it is set, and that happens to be a desert suburb in Peru that was apparently founded by persecuted witches fleeing the Peruvian Inquisition.

kids wandering wrecked houses wearing witch hats.

Speaking to me last year, Oldenburg explained that 1000 Heads Among the Trees is a virtual recreation of his ghost-hunting trip to Cachiche. While there, Oldenburg stayed with a brujo (sorcerer) called Don Miguel Angel. His voice and likeness appears in the game as he tells you about the town and its legends, as do a couple of other townspeople Oldenburg spoke to during his stay. Likewise, the ambient sounds in the game are direct recordings of Cachiche’s natural soundscape that Oldenburg brought back. And the town itself is recreated as faithfully as Oldenburg could manage, using his photographs and Google Earth to get a rough layout and look that matched the place, even if it isn’t “house-for-house.”

Knowing all of this puts you in a ghostly position—almost like an out-of-body experience—as you venture through a facsimile of a real place. And if it’s creepy then it’s not necessarily because it is deliberately manufactured to be, but because Cachiche itself is in reality. As I walked through the dark streets, following along with Oldenburg’s thoughts in his journal, I couldn’t help but think about how unnerved I was sat behind a monitor imagining doing this in real life. I don’t know if I could hack having this experience first-hand. But Oldenburg did.

The idea is to take photographs of ghosts, and to this end the locals you talk to in Cachiche will point you towards the tall structure of a witch, whose daughter and grandson still reside in the town (you can talk to them in the game). They’ll also point out the seven heads, which are palms trees that mysteriously curl back into the ground that they grow out from. You also get the opportunity to hop in a taxi to see the eerie lake that Oldenburg was taken to as well as an old abandoned house on a hill that is supposedly used as a meditation retreat.

what works here is that uncertainty space

Oldenburg has embellished on the horror in places. There are hallucinatory visions of kids wandering wrecked houses wearing witch hats. In a number of places you’ll see shadows that don’t have a body. And you’ll also see people discussing secrets in dark rooms or running past you hurriedly from behind fences. But this only adds to the underlying feeling of something sinister and ominous present, watching you, following you wherever you go; it’s not the source of it. What establishes the tone, along with the environment, are the tales that you are told by the locals.

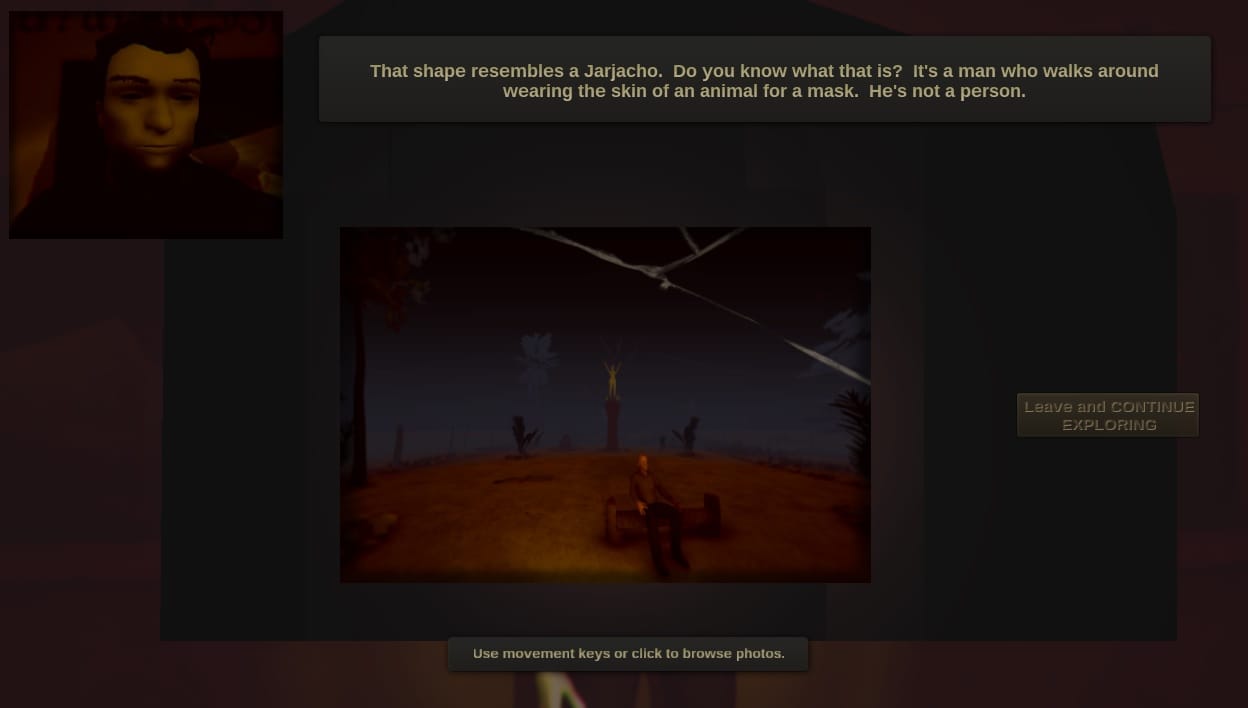

You can converse with people using the photos you take as a starting point. Show them a picture of a man and they might tell you that he’s a demon wearing skin as a mask. That example is less convincing than others but it still might give you pause when you come across that particular local again. The better tales are those that give one of the dark buildings some history: one is known as the “devil’s house,” others are places of bad fortune, or are believed to be haunted. All of the responses you get are based on interviews that Oldenburg conducted with the people of Cachiche. He let them indulge their “imaginations and collective unconscious” rather than trying to pin down facts, instead allowing the suspense of all these evil fictions to swell.

As with the Blair Witch legend, what works here is that uncertainty space, as the legends you are told have a ring of truth to them, and you can’t immediately outright dismiss them. You may think that the concept of a witch to be absolute rubbish but it’s different when you’re supposedly in the vicinity of one. Would you dare risk being so ignorant when something so sinister is all around you? And all the time, as you pass the places you’ve heard about in the game, this is playing on your mind. Is there something here to find? Could a ghost or a demon be lurking behind this corner? Is the witch’s spirit still here in some form? You start seeing it in the wild eyes of dogs, burning effigies in lonely fields, a rustle in the grass gives you a fright. With enough of this you may begin to accept the legitimacy of those tales. Oldenburg’s notes in his journal reflect this thought pattern and it’s in recognizing this that I knew he had achieved what he set out to do. And that is to explore the unsettling margin between documentary and the unknown.

1000 Heads Among the Trees will be out on September 1st. You can find out more on its website and also vote for it on Steam Greenlight.