Dust to Dust

It might be easy to question the logic of building a 1:1 scale model of a Counter-Strike map out in the desert (read: life-size!). But for Aram Bartholl, this is a natural progression of his work that explores the permeable line between online and offline worlds. What’s even more remarkable is that he’s been doing this since before social media became our zeitgeist.

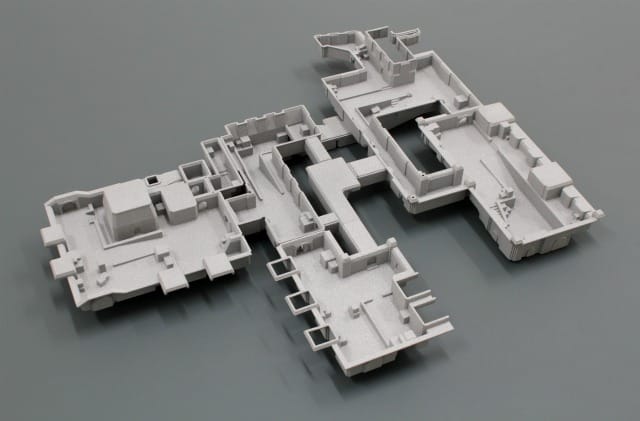

Dust, which will be built this year with a commission from Rhizome, goes beyond elevating popular culture into the realm of art. Bartholl’s project questions the physical nature of reality and highlights the moment of discomfort that occurs when something in the digital world infiltrates real space. In a 2004 public installation, Bartholl made replicas of the recognizable wooden crates from Counter-Strike’s “de_dust” (or “Dust”) map, highlighting their change in function from a packing medium in real life to a strategic and spatial mechanism for a competitive shooter. At the same time however, like the environment of “Dust” itself, the crates were “generic, duplicatable and locationless,” underscoring the repetitive elements of game design.

In 2006, Bartholl began dropping oversized Google Map markers—a signifier of our tech-enabled lives—into real spaces. In doing so he whimsically acknowledged the revolutionary shift Google has placed on how we perceive location, something the company would later repeat with architecture (Google 3D), cities (Google Street View), and now building interiors (Google Interior View). “The goal of the Google Map intervention is to elicit an unsettling feeling,” Bartholl says. “You know [the Google Map marker] so well, but it doesn’t belong there.” In 2010’s Dead Drops, USB sticks embedded into walls required you to physically attach your laptop to access and share files. Bartholl says Dead Drops was partially about making it an “adventure to go back outside,” reviving the surprise of not knowing what you will find.

Dust takes this all further: it’s about placing you into the online world, but in a physically real place. It’s a reversal of the Google Marker—you may know the space of Dust well, but you don’t belong there. The project is ultimately less about identity or belonging, however, than a shared experience in popular culture. At the height of its popularity, “Dust” was the most-played first-person shooter map in the world.

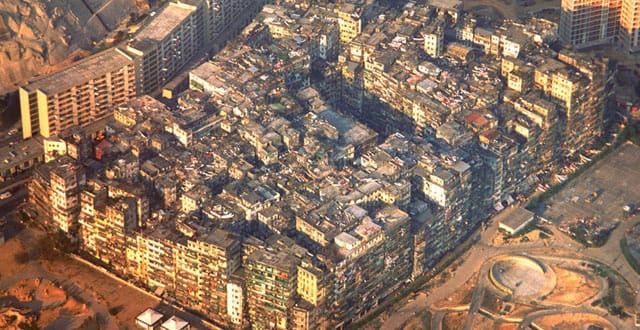

Is Counter-Strike’s “Dust,” tested and tweaked repeatedly for navigability, lines of sight, and timing, actually more real than today’s generic retail megaprojects or cities like Dubai?

“So many people have been to the same worlds in computer games that it becomes cultural heritage at some point … and why not build a museum or memorial to space which only exists on computer screens?” he asks. Dust also marks a certain moment in the evolution of videogames. In his Rhizome proposal, Bartholl writes that unlike games today, with their endless terrain, “game spaces of the 1990s were still limited in size due to graphic card and processor power limitations. A respectively small and simple map like ‘de_dust’ offered a high density of team play with repetitive endless variations.”

Finally, Dust is a commentary on the artificiality of real spaces. Is Counter-Strike’s “Dust,” tested and tweaked repeatedly for navigability, lines of sight, and timing, actually more real than today’s generic retail megaprojects or cities like Dubai?

Unlike elsewhere in the online world, Bartholl says that in a game space, “space becomes a very present quality. There’s a plot but you’re free to go in many directions. You have to figure out where to go, and once you’ve been at that space, you remember it.” Furthermore, it’s more difficult to passively take in cues because we’re viewing on a 2D plane. As such, “architecture is a very important quality in that it controls the game very much. You need to recall every centimeter in these game maps,” Bartholl says. Equally fascinating is reading about the creation of “Dust” from its designer David Johnston, who admits the map was a combination of “thievery and luck,” inspired by screenshots from the then-unreleased Team Fortress 2 and built one room at a time.

Bartholl also sees a lot of cliched architecture in game design, citing World of Warcraft, and doesn’t feel that gaming architecture has kept up with the development of its action dynamics. “I’m still waiting for the point where ‘realism’ has been achieved and games become more abstract again,” he says . To that end, Dust isn’t going to be an exact replica of the game map—it’s going to be deliberately constructed from concrete, without any distinctive colors or textures, to create that level of abstraction.

His hope is that gaming may have a real place in high culture. Bartholl would love to see a famous architect like Zaha Hadid designing videogames. Currently building models for Dust at different scales with architects and engineers, he hopes to set it up in a remote place—in the desert in Saudi Arabia or China. He wants people to have to travel to see Dust, and hopes the site can “become a mecca, a quasi-religious place for the gaming scene.”

Block Quotes covers the architecture of videogames and their relationship with the real world (and vice-versa). Michelle Young is the founder of Untapped Cities, a website about urban architecture and design.

Photograph by Aram Bartholl