Can a team of Pixar and Muppet Studios vets make good on the promise of Milo?

The other morning I booted up an app called The Winston Show and, I swear to you, talked to a jellybean for awhile. He asked me how I was doing, and, being generally distrustful of a jellybean’s conversational capabilities, I answered that I was doing poorly. He expressed condolences, offered some advice. We talked for a bit about sports. Later, he told me a story and let me help choose the ending. I warmed up to Winston, eventually; at his suggestion, I took some pictures of myself with a stupid hat on.

This moment—me wearing a stupid hat—was the end result of years of work from the San Francisco-based developer ToyTalk. The company, which was formed in 2011, announced itself to the world with a video released at the end of last year. In it, a bright-eyed youngster totters into her room, sets a beloved stuffed animal in front of an iPad and, thanks to the magic of technology, begins a whimsical conversation with the newly animated friend. It’s inspiring stuff.

The Winston Show is their first release since that video, and, while it’s not the realization of that video, it is a defiant first step towards that experience. It also forges a new path for the synthesis between artificial intelligence and voice input, a technology that has been widely but ineptly explored since the rise of the Kinect.

From his time with Pixar he learned to focus not on creating a realistic experience but “a believable one,” as he puts it.

This technical innovation is thanks in large part to the efforts of CTO Martin Reddy, a Pixar vet who, in more hirsute days, served as the hair model for Mr. Incredible. From his time with that company he learned to focus not on creating a realistic experience but “a believable one,” as he puts it. The distinction is important. “That’s very different from trying to say that you’re fooling a person into believing (they’re talking to) a human being,” he says.

Their only goal with Winston has been to create a character that children want to spend time with, and in that effort they have had to eschew much of the conventional wisdom about AI and voice input. Rather than investing in speech synthesis, for example, they employ an actor to portray Winston. Rather than having conversation threads dictated by engineers, the engineers created a system that allowed artists and writers to completely dictate the flow of conversation. “It should not,” Reddy says, “be people like me writing the content. That would be a pretty bad idea, we think.”

Another key component is the structure of the program. When first told to just talk to the computer, children didn’t know what to say. Similarly, when I first booted up the app I looked to test the boundaries, to “break” the toy. But by setting it up as a talk show, the authors are able to carefully circumscribe the nature, type, and rhythm of conversation. And because the responses are authored and characterful, something strange happens after awhile: we give in. We wear, as it were, a stupid hat.

For all the talk of immersion in videogames, little is said of coercion by them.

For all the talk of immersion in videogames, little is said of coercion by them. Perhaps the willingness comes from the manner in which we interact with Winston. It’s nice, in other words, to talk, and to feel heard. “We have been communicating through talking for an awful long time, and so it seems like it’s an innate part of us as human beings,” Reddy says. “It hasn’t been explored an awful lot in entertainment.” This changes the rubric for interactivity. Instead of twitching a thumb and seeing immediate results, we speak and wait for them. These rhythms are still largely unexplored in games, and ToyTalk’s team is working hard to find the sorts of pauses and replies that feel right.

Reddy hopes that ToyTalk gets this right, first, with children, but eventually sees the technology scaling upward, to adolescents and then adults. But the question then becomes, to what end? Why do we need to talk to our iPads? The writer Sherry Turkle has questioned our willingness to do this, to offboard human interaction to machines. We are already employing robots as caretakers for our elderly and turning to them to help teach our children, but the dialogue between these generations ought to be preserved, she says. “We are literally building the machines that will allow their stories to fall on deaf ears,” she has said.

It’s not meant to replace the time children spend with their parents but the time they spend with the TV.

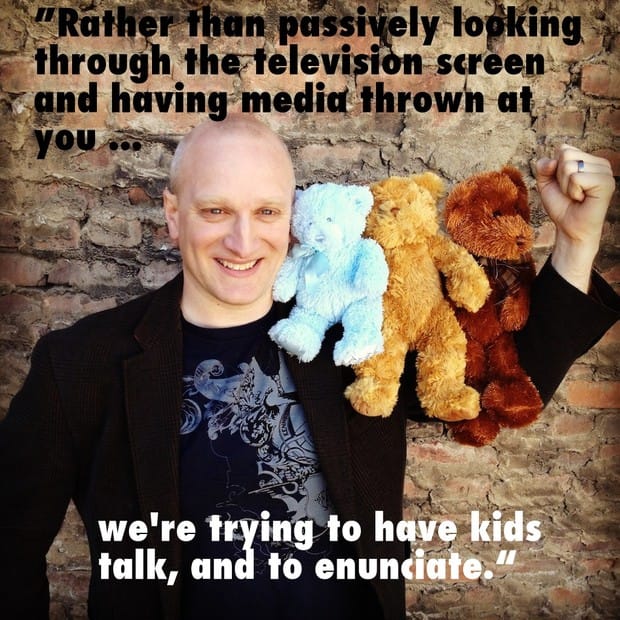

Reddy sees Toytalk’s work not as a surrogate for human interaction, but instead as a model for a more inclusive form of entertainment. It’s not meant to replace the time children spend with their parents but the time they spend with the TV. “Rather than passively looking through the television screen and having media thrown at you,” he says, “we’re trying to have kids talk, and to enunciate.”

And, at least in early testing, it’s bringing parents into the fray as well. Reddy says that when kids play with The Winston Show, they don’t tune out of the world around them. When parents walk by, they often chime in on the conversation. It’s easy, after all, to want to join in when you hear two people talking. For people looking to see videogames develop new audiences and types of experiences, this is an exciting prospect indeed.