In 1981, the Canadian folk singer Stan Rogers released “Northwest Passage,” a hearty a cappella song that compares travelling across Canada to the explorers who first blazed a trail through the undiscovered continent. It’s a song about Canadian history, the desire to explore, and the ultimate need to return home again, all condensed into the image of the titular Northwest Passage and Sir John Franklin’s ill-fated attempt in 1845 to draw one warm line between the Atlantic and the Pacific Oceans. As politicians are fond of mentioning, it serves as something of an unofficial Canadian national anthem: “Northwest Passage” blends northern imagery, pioneering history, and a dash of Canadian je ne sais quoi.

Now politicians are pleased to mention the song because they are keen to blend patriotism with Arctic national policy. Until relatively recently, the amount of summer ice in the Arctic Sea prevented regular use of the arctic waterways. Thanks to climate change, the possibility of using the Northwest Passage year-round has become a realistic prospect. Canada considers the waterway to be Canadian internal waters; the United States and other countries consider it to be an international strait, like the Strait of Gibraltar, and subject to no limitations on passage. The dispute over control is still in its early stages, but the groundwork for a diplomatic conflict is being laid even now.

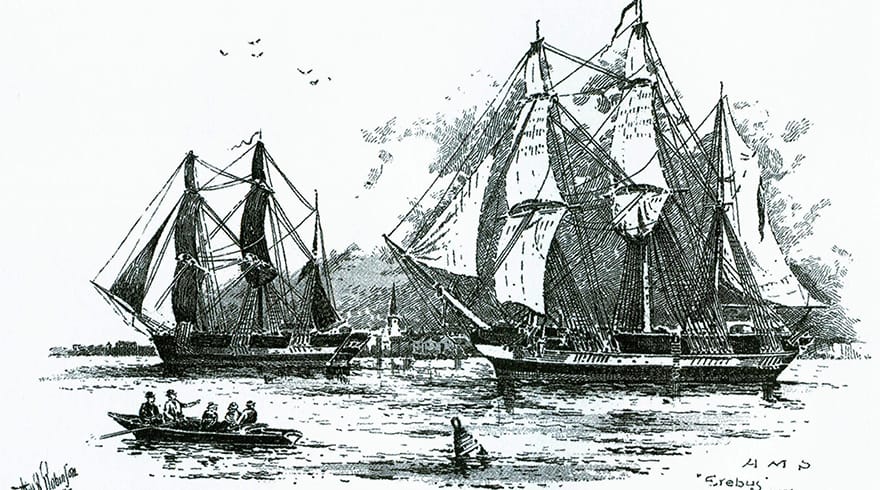

The Government of Canada—known also as the Harper Government, after its authoritarian Prime Minister—has, in the past, made a number of symbolic gestures designed to solidify this link between Canada and the Northwest Passage. In 2009, Canada’s Parliament unanimously renamed the Northwest Passage the Canadian Northwest Passage. In September 2014, a press conference led by a member of Parks Canada and Prime Minister Harper announced the discovery of one of Franklin’s ships; a month later, Harper announced, to resounding applause in the House of Commons, that the ship was confirmed to be the HMS Erebus. Along with an increase in Arctic training missions by the Canadian military and the building of a new naval base on the shore of Baffin Island, the symbolic subtext of the appropriation of Franklin’s expedition is obvious: the path through the Arctic Archipelago is ours.

The most recent item in this campaign is a Youtube-based “choose your own adventure” game called Journey Into the Arctic, where the player is invited to discover the Northwest Passage. Ostensibly a fun way to introduce Canadians to their northern heritage, the game serves as a trivial propaganda piece that reinforces contemporary political goals. One of the first options in the game allows the player to travel around the southern tip of South America, known as Cape Horn—just kidding: your ship crashes, and you are retroactively railroaded towards Greenland. Other incorrect choices are similarly corrected: exploring the wrong channel ends with the player being placed on the “right” one; the choice between buckling down for the winter or trying to sail through the ice leads you to make winter quarters in either case. Even choosing to return home sees the player punted back to the Arctic sea, after the disapproving voiceover says, “Cautious people rarely make history.” In essence, the game is designed with only one real path in mind: that through the Northwest Passage. All other decisions are merely mistakes or errors, incorrect histories to be rectified and forgotten.

The only answer to the question of why this illusion of choice is offered in the first place is to frame the northern mission as a kind of providential Canadian destiny. Again, the game offers no real failure states: crashing your ship punts you towards the “right” option, as does allowing your ship to become locked in ice and using European sleds instead of Inuit dog sleds. The player is inexorably placed onto the “right” path, which includes a moment of romanticized cooperation between European explorers and aboriginal Canadians. There is only a nationalistic subtext to be found beneath the veneer of choice, the cutesy animation, and the patriotic narration. Given the current political climate surrounding the Northwest Passage, it is hard not to imagine that this was the game’s point all along.

propaganda games are nothing new

But propaganda games are nothing new. America’s Army, a first-person shooter produced by the U. S. Army and designed to foster recruitment, is the most commonly invoked example. Less morally ambiguous examples of the genre include the White Supremacist ZOG’s Nightmare and the Chinese MMO Anti-Japan War Online. Leaving aside the complicated politics of the first example, the latter two games all reinforce the conclusions their ideal audience already holds: that the Japanese are enemies of China, and that governments are enthralled by an organized Jewish conspiracy. These ideas are then reinforced by specific game design choices and by the absence of material that might challenge this viewpoint. These propaganda games are, in essence, interactive echo chambers.

Journey into the Arctic operates the same way. There are no mentions of the cannibalism that marked Franklin’s lost expedition, nor are there references to hypothermia, pneumonia, tuberculosis, and lead poisoning from the tinned food. Granted, scurvy is mentioned, but only as a result of rejecting the Inuit’s help; the player is then made to accept Native assistance. Instead of these historical realities, there is merely the romanticized quest for the Northwest Passage, and the ugly subtext that its control is a kind of Canadian manifest destiny. Though it is a brief creation, it serves the same purpose as the games listed: to reinforce an agenda, to convince by repetition and not by innovation or argument. Though its tenor and motives are not as horrifying as that of ZOG’s Nightmare, Journey into the Arctic is no less sinister for being small.

Yet these kinds of games are remarkably insubstantial—an up-to-date version of Joseph Conrad’s papier-mâché Mephistopheles from Heart of Darkness: “it seemed to me that if I tried I could poke my forefinger through him, and would find nothing inside but a little loose dirt, maybe.” Once propaganda games have their mechanics pointed out, they lose all conversionary force; when unveiled, they are shown to be merely bad videogames.

its control is a kind of Canadian manifest destiny

The past few days have seen the resignation of Paul Watson, a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist, from the Toronto Star. Watson alleges that the Star blocked the publication of a story that details the “distorted and inaccurate accounts of last fall’s historic discovery of Erebus in the frigid waters of eastern Queen Maud Gulf.” He has since resigned in order to continue work on this story. Given that the Prime Minister’s Office has repeatedly shown an iron grip on various national campaigns, Watson’s allegations, at this stage, have some merit. At the same time, his accusations, along with gestures like Journey into the Arctic, outline the modern take on the nineteenth-century’s quest for the Northwest Passage: not discovery, but control.

///

First image entitled “HMS Erebus and Terror,” acquired via public domain.