Carson Lynn: Sculpting with virtual light

“If I go into a video game and I take a photograph, there’s no lens there… but why should I be excluded from the definition of photography?” Carson Lynn’s body of work dwells on the concept of refusal—the refusal to define photography in conventional terms, the refusal to use game engines as intended, the refusal to tolerate heterocentric virtual landscapes. Consequently, the artist’s series of Machinima films explore what it means to queer both gamespaces and real-life landscapes. Proposing the glitch as a site of potential, their projects also push the definition of image-making deeper into the digital realm.

We spoke with Carson about the synonymous relationship between photography and game worlds, the sublime landscapes surrounding their childhood, and the power of introspective, ‘stop-and-smell-the-flowers’ moments within gameplay.

MAKING WITH MACHINIMA

Where did you grow up, and when did you know that you wanted to be an artist?

I grew up in the suburbs of Calabasas. My first foray into art was making little machinima videos using Halo. There was this one show called This Spartan Life, which is a talk show within Halo 2. They would bring actual players on as extras.

I was part of this community. When the director would want the people fighting in the background of their interview shot, I would come on. There’s only one shot made into the final show, where you can see my blue avatar in the background shooting his gun into the air. That show dealt with a lot of higher concepts about media theory. Being 13 at the time, I didn’t understand any of it. But it’s seeped into my subconscious in this exciting way.

In high school, I started doing photography and Photoshop work. I got my undergraduate degree in photography and imaging. Halfway through, I realized I didn’t want to be a commercial photographer. I wanted to be an artist. I started taking inspiration from digital imagery, combining video game worlds with real worlds and really playing around with how much of a photograph needs to be created from reality to be considered a photograph.

Around 2012, there was a real shift in the photography world of defining what photography was—phone photography was getting really popular. All my teachers would say, “Oh, you took it on a phone? It’s not a photo. Anyone could take that. You have to take it with a real camera, or you have to take it on film for it to be real.”

I pushed back. A lot of my projects at the time were either phone photographs or manipulating photographs that include 3D imagery. It wasn’t until last year that I rediscovered machinima and game art, took my photographic eye, and applied it to virtual worlds.

You studied at ArtCenter for both your BFA and your MFA. How do you see your practice being shaped by both these programs and these curriculums?

ArtCenter has definitely helped me to analyze my artwork from every single angle. One of the downsides, though, is that ArtCenter is also a very commercial school. You’re only able to convince people that what you’re doing is good is when you can convince people that there’s either an audience or money in it.

When I was doing game art, no one was taking me seriously. And then when I was like, Oh, no, I’m doing machinima. Here’s the history of the medium. Once I did one piece in machinima, and people were on edge. And then I got it at the Milan Machinima Festival. People were like, Oh, this is a thing.

The plight of any game artist convinces people that game arts is a thing, or it’s also the inverse of just accepting that some people will never accept game art as a thing and instead of focusing on people who know about games.

DIGITAL LIGHT

Was there a moment that marked the shift from working in more traditional photography to photographing within the game space?

I hear people refer to photography as a lens-based medium. I always take offense to that. Many people don’t use lenses in photogram work or creative darkroom work. If I go into a video game and I take a photograph, there’s no lens there, but why should I be excluded from the definition of photography?

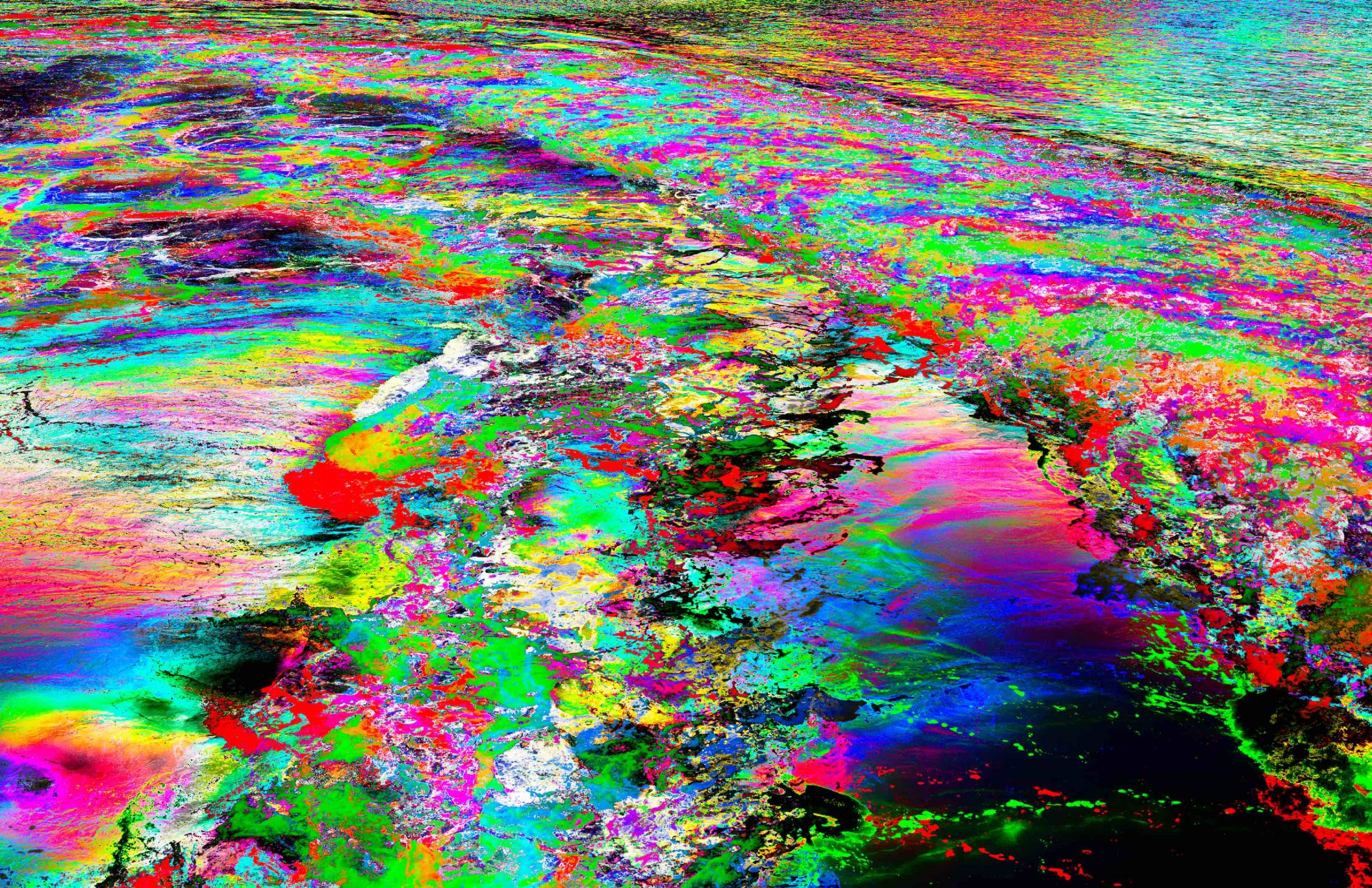

I consider photography more of a light-based medium. I even would go so far as to say virtual light is part of that. In high school, I learned about tricolor separation, a technique where you take three photos, one with a red filter, a blue filter, and a green filter. You then recombine them to create a complete color image with bizarre, layered rainbow colors. It was how they made color photography before the invention of color film. That was the first time I thought about manipulating light.

I revisit tricolor separation quite often because it has such a unique visual style to it. I’ve been experimenting with being that in games that have a day-night cycle. You can get this weird gradation of colors. Especially when you zoom in to 100%, you get these little differences in the image’s noise. You zoom in, and it’s this entire rainbow gradient.

Tricolor separation images taken in real life pose an interesting problem: you need to keep the camera still during each of the three exposures. So, if you want to take a tricolor photo and utilize the movement of the sun, you have to wait for the sun to move. However, many games either have a truncated day-night cycle, or allow you to move the sun where you want it. Your camera never moves without your input, so it’s much easier than taking these images in real life. But also, these images can feel a bit too perfect; too clean. When you use physical captures for tricolor photography, you can zoom in to the pixel level and see that every single pixel has a rainbow hue. The camera captures even the slightest quantum change in light, which is not something video games can emulate yet.

How has the landscape of Southern California impacted your work?

The mountains of Southern California definitely have an impact on me. I grew up on the side of a mountain, higher up. You can see more mountains in the distance. I remember one particular moment of watching the mountains as the fires came by, and you could see the fire going by and the smoke coming off of it.

A couple years ago, I went to Pennsylvania for a vacation. I was like, “Everything so flat. There are no mountains. What’s going on?” The presence of those mountains is one reason I like video game landscapes so much, especially in games like Destiny. They take extreme care in making sure that the landscapes can almost work as waypoints.

In some of the developer commentary videos that they’ve posted, they refer to these landscapes as postcards, where essentially you get to a location, and then you look out, and you see the giant landscape in front of you. Then there might be a building often at a distance that has light from it. That’s the postcard shot.

Destiny and the Halo games have also been very aware of the impact of landscapes. It was Halo 2, which first introduced the lowered reticle. The aiming reticle is not in the center of the screen. It’s slightly lower, which means that the gun model is not completely in your view. But also, you can see more of the landscape. In Halo 3, the landscapes become a lot more developed. They introduced this lowering of the reticle so that you can see more of the landscape. It’s also because you get a higher, vertical view. So, if there’s something up above, you’re able to see it more clearly.

There’s a photographer named Bryce Bischoff, who did this series called Bronson Caves, where he basically went to these man-made caves in LA and created ghost images. They’re 15-minute exposures. He dressed himself up in these giant sheets of colored cardstock and would dance around and do his performances.

These multicolored ghosts are supposed to represent the ghosts of the movies that had been shot at these caves. The old Batman series was shot there, as well as a bunch of other old western films. It showed me how much you can push photography, how much you can glitch photography when you use it in an unintended way. A lot of my work earlier on was about glitching photography, even the definition of photography.

THE BIASES IN LANDSCAPES

The history of landscape photography is strongly tied to the history of colonialism, of conquest, and in American landscape photography, the idea of the ‘manifest destiny. It seems that landscape photography is a neutral art, but in reality, it isn’t. What are the specific ways you see technologies, narrative strategies, and landscapes in video games as non-neutral?

In reality, anything that is created by a human is not neutral. Many game creators treat games as this space that shouldn’t be intruded on by outside parties. So you get this feedback loop of, “Oh, we’ve been doing this, and we’ve been doing this, and we’ve been doing this.” And then people don’t think about why.

No Man’s Sky doesn’t think about the colonial aspects of going to a planet with a name, then discovering it, and then naming it your own. It’s weird, too, because you see the artifacts of other civilizations there. You look at that and go, oh, well, this mine now.

Minecraft has a little bit of that too, especially with the villages, or you can go in and raze a village. And take all the resources. You never think, Oh, what I’m doing is wrong somehow. Yeah, a lot of game mechanics are treated as being neutral in that way. But in reality, they are much more loaded.

I think my work is a critique of some game systems. Game systems are not neutral. Some systems need to be addressed. Because I feel like many games are like, Oh, well, all first-person shooters have sprinting. So, we need to sprint. Can that be done in a more interesting way, or can this be done in a way that is more accessible?

Every game system should be open to being examined for change, but it’s a case-by-case basis. You can make an argument for some of the game systems that I like. Like the first-person shooter, you could say, why does it need to be a shooter or something like that? Why does there need to be violence at all?

There’s something about those games that are appealing to me. I don’t know if I’m ready to critique that aspect of it yet.

How does your creative process usually start?

Normally, I find a technique that I find some sort of aesthetic interest in. Then I go from there. With Oddball, it was that I could remove the HUD (heads up display) in the game through this particular mod. Then it was exploring what I could do with that from there. That’s been my artistic practice for a while, where I basically find a technique and then explore it. Then I figure out the concept I want to portray with that technique afterward.

That started with photography, where I find a Photoshop filter or something weird to do with the photograph or the camera. After experimenting with that for a while, I think about what I want to say with this technique. That’s been mostly working for me. There are some instances where I find a technique, and I’m like, Okay, this is great. What can I do with this? And then I cannot find a way to create a theme or a reason for that technique to exist. Then that goes on the back burner.

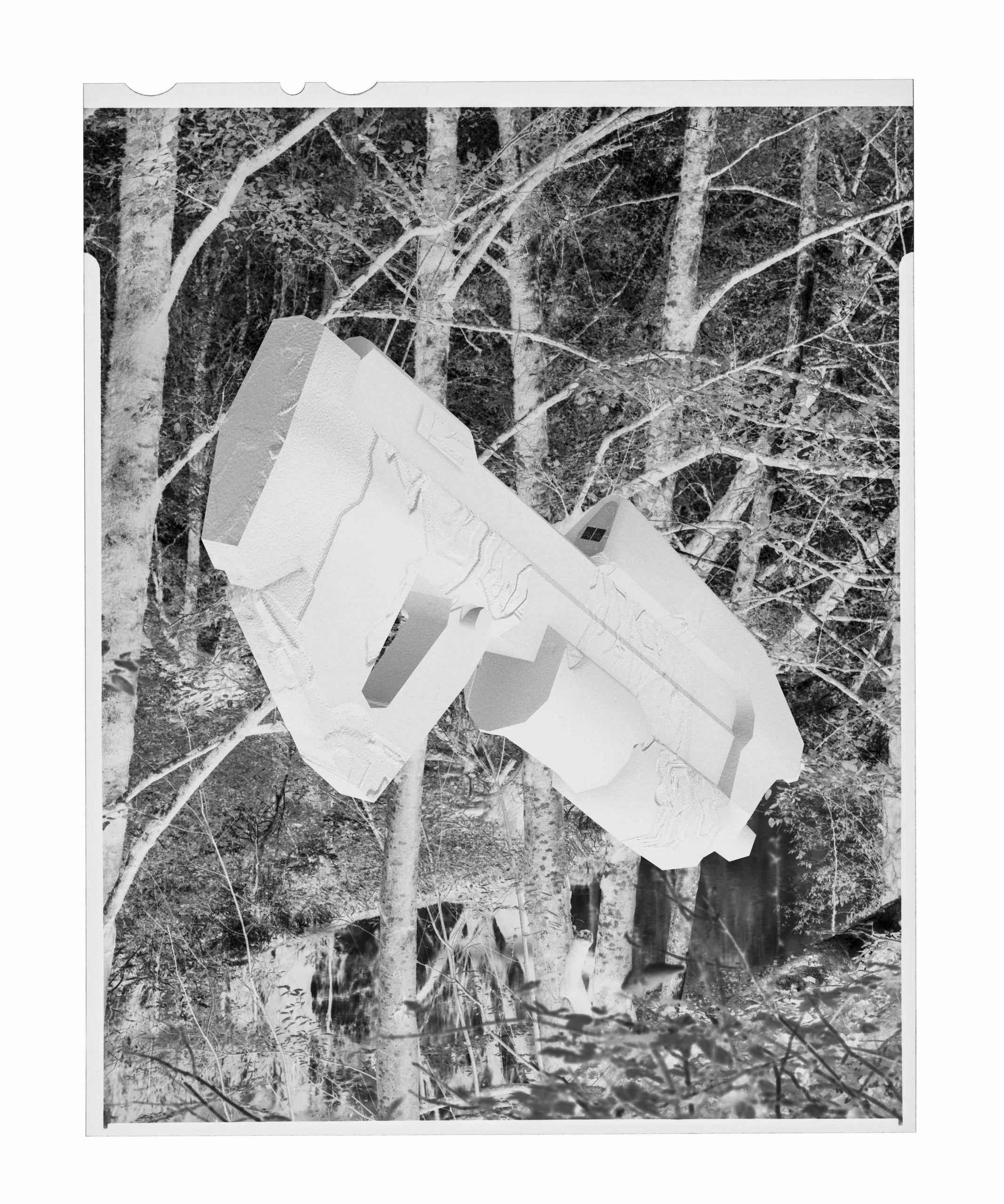

My thesis show I Want uses the normal mapping colors. That started back in 2016 as a photo project because Photoshop released the filter where you could turn a photo into a normal map. I just like playing around with that. I really like the way this bluish lavender color was something that was underrepresented in art. It provided this soft palette that I haven’t really experimented with before.

I tried combining it with film photography and getting these weird textures. But it wasn’t clicking. It was only until I Want where I discovered a mod that I could implement into the games and create that visual style on the fly that I thought, Oh, I can combine this with machinima. It can play into the idea of what’s going on underneath these games. It’s revealing of how the games work. Then I started playing around with that and bringing in the color palette to the concept.

Your machinima film, Oddball, utilizes found text of people playing Halo 2. What was your process for this—specifically, how did you go about incorporating text, silence, and image for this piece?

Oddball first started as this ambient landscape shots of these Halo 2 multiplayer maps. I decided to focus on the homophobic chats that I’ve encountered in these games. I was thinking about how Halo has a text feature that is normally used for the kill theme, showing X player killed X player. The way that text comes on screen—it pops on, stays for a second, and then slowly fades away. There’s part of that felt like this, being there, where it hits you and then fades away, but it’s still kind of there. So I re-created the text in Adobe Premiere to match this effect.

That was a big moment for me, using the actual game systems to decide its aesthetics, rather than putting my own aesthetic in. I’ve been beginning to use a lot more text in my work. Using the game systems to the side also makes it so that the text fits with the world.

The game developers chose that color text for a reason; it fits really well with the color palette of the game. It’s visible pretty much every time you look at it, except maybe when you look at the sky.

THE ORIGINS OF I WANT

I Want was an online show due to the pandemic, but it was originally intended to be a six-channel video installation. At what point in your process do you decide the final form or medium of a project?

I Want was my graduate thesis show at ArtCenter. The installation was bound to the room that I had been given to have my thesis show in. That influenced how I did the project. I thought, Okay, how can I show this in a room that size? How many TVs do I have access to?

I was supposed to have my final review on the 18th of March. We closed our school on the 14th of March. So I thought to put the projects in unity and remake the building, and then put the videos up, and then I can work on it through there.”

Once I had the base of this re-creation of this building, I started incorporating the concepts that I was exploring in the project or in those videos. I then brought them into the virtual installation because I was much more open. I had all these options to me outside of the gallery. It doesn’t have to be a courtyard that exists outside of the physical gallery. It could be a giant rainbow landscape that you can wander around in.

What were the concepts you wanted to explore in I Want? I’m especially interested in the idea of refusal—of using technologies in ways that they’re not meant to be used?

A lot of that has to do with the glitch and refusal, especially in terms of the glitch in relationship to machinima. Halo 2 machinima was mostly only possible due to a glitch where you could get rid of your weapon. That allowed you to open up the entire screen to create videos with.

The project’s inspiration was this moment where you can throw out your weapon, refuse to give into the game systems, and instead use the game for something else.

It was also inspired by a particular moment I had while doing a raid in Destiny 2, where raids are these six-player high-level activities where it has to be super tactical. You have a lot of communication between people. I was wandering past the landscape. Then I stopped and looked at it, and I sat there for a little bit. So, I was mesmerized by the landscape.

Many of the landscapes in Destiny 2 were inspired by Caspar David Friedrich and the sublime artistic movement. I was admiring this landscape. And then a player came up to me and was like, Hey, we’re playing. Get moving. But he also had a couple homophobic slurs in there because apparently, sitting around makes you gay, which was a moment where I thought, Oh, is this not normal—to want to sit and enjoy a landscape.

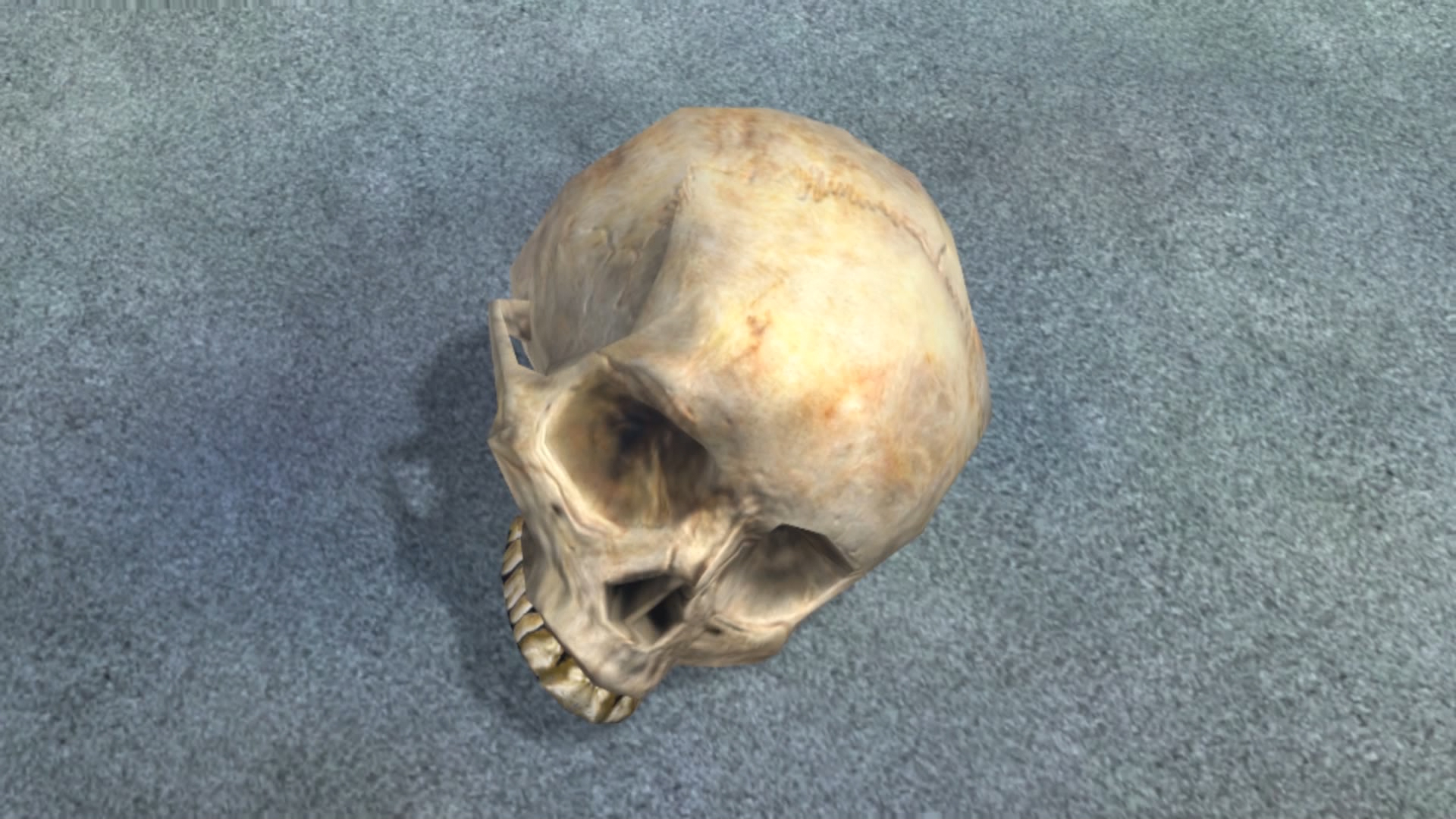

The motif of stopping and smelling the flowers is the impetus for I Want. But it also spawned out of introspection as to why I like the avatars that I like so much. If a game allows me to hide my face, I always hide the face of the avatar. I like giant, bulky armors that never show signs of the human on the inside. I was looking down like, Oh, you think that could be for a reason. I’m hiding from something.

That’s why there are images of my Dark Souls avatar and my Skyrim avatar, and then the Halo avatar because they all have these big bulky armors that have no sign of the human underneath. They’re all “edgelord” exteriors that are meant to shield from potential damage.

Why do I gravitate towards that when I know so many other players create themselves in the game? And then they go around and ask themselves, versus me and, I don’t want to be this.

“In reality, anything that is created by a human is not neutral. Many game creators treat games as this space that shouldn’t be intruded on by outside parties. So you get this feedback loop of, Oh, we’ve been doing this, and we’ve been doing this, and we’ve been doing this. And then people don’t think about why.”

THE GLIMMER IN THE GLITCH

I love the idea of the glitch being a tool for liberation. Are there other examples of glitches in games that you’re experimenting with at the moment?

There’s a glitch where it repeats the pixels that you see. It repeats them over and over again. That was the inspiration for one of my photography projects, Walking Simulator, which I then took those photographs and turned into textures. But then I made a game that uses that glitch.

Wherever you look, it fills in textures based on whatever pixels you are looking at. So, you’re able to create your own abstractions with it. It also depends on how fast your computer is and how big the resolution of your screen is. Everyone has a different experience with it.

There are these specific glitches in Halo 2 called super bounces, where essentially you walk into a corner for a specific amount of time, and then you fall down. For some reason, the game doesn’t know how to calculate your change in elevation. So, it pushes you up to the very top of the map. Those glitches, you can use that to then get out of bounds and explore different things. In a lot of older games, it’s like, “Oh, I can explore these weird, unfinished areas, these things that aren’t meant to be explored.”

Destiny 2 is full of glitches, which I feel like some people don’t like, but that’s probably the main reason I like it so much. There are weird holes in geometry that you can just jump into pretty easily. It’s like no one playing normally would find it, but you have to be looking for it. Then all of a sudden, you’ll find this hole. You can just go in there and see how the actual game is made, and landscapes are crafted.

What are you working on now?

I’m doing a project about homophobia in game spaces. One of my teachers said, Well, why do the words hurt you so much if you’re also getting killed in the game? I’m like, Those are two completely different things. The violence is not something that gets desensitized, but it’s a part of the game mechanic. If there wasn’t any violence involved or anything like that, there would still be the same core mechanics. But the language is something that passes through every single game. It’s something that seeps into your psyche, causing internalization of homophobia and stuff like that. So, it’s something very different from virtual fake violence versus real, vocal violence.

Credits

Interview conducted in November 2020. Edited and condensed for clarity.